by Rob Callahan

We Americans tend to sap our holidays of any holiness. Memorial Day, for many, serves less as an occasion to reflect upon our fallen soldiers than as an opportunity to celebrate the advent of summer’s hedonism. Presidents Day, in theory, ought prompt us to consider Washington’s and Lincoln’s respective roles in the establishment and preservation of a union predicated upon principles of freedom and equality, but mostly we just observe it as yet another occasion for retailers to offer sales.

The holiday now upon us, Labor Day, perhaps best exemplifies this American habit of stripping national celebrations of their underlying significance. Outside of the dwindling ranks of the labor movement, few regard the holiday as a commemorative event. It marks the close of summer, a late-season opportunity to barbecue, the date beyond which the arbiters of dress code look askance at seersucker. For most, Labor Day is all about leisure. The holiday nominally honors organized labor, but we are too preoccupied with those hot dogs and that final outing to the beach to think over much about the empowerment of working folks through the exercise of solidarity.

One might argue that missing the point of Labor Day is, in fact, the point of Labor Day. In certain respects, the original function of the holiday was to distract from, rather than to celebrate, the struggles of working people to improve the conditions of their employment through collective action.

Labor Day became a federal holiday in 1894 under President Grover Cleveland, who signed the law establishing it not long after ordering federal troops to suppress a nationwide strike of the American Railway Union against the Pullman Palace Car Company. Thirty strikers were killed and scores wounded in the resulting violence. In the immediate aftermath of mobilizing troops to defend management’s interests in a labor dispute, Cleveland felt some pressure to make a conciliatory gesture towards labor.

In instituting a September date as the official national celebration of organized labor, Congress and Cleveland established a more palatable alternative to May Day, which is celebrated throughout the rest of the world as a commemoration of the struggles of organized labor. May Day memorializes the General Strike of 1886 and subsequent Haymarket Massacre in Chicago, critical milestones in the movement for the eight-hour workday.

The fierce and sometimes bloody fight for a shorter workday and workweek is a thread that ran throughout organized labor internationally from the Industrial Revolution forward. Working people worldwide rallied around the slogan “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will.” Over the course of decades of struggle, the labor movement set the eight-hour workday and the five-day workweek as the standard for much of the industrialized world.

If you are working a union job and have Labor Day off, you should recognize that you owe your leisure to a long tradition of solidarity.

Thus, Labor Day has ceased to be a meaningful commemoration of organized labor for much of this country, and even in its origins as an official holiday, Labor Day afforded a milquetoast alternative to another, more radical focal point on the calendar. But what significance does all this have for us today, almost 120 years after federal recognition of the holiday? That time was long ago; those folks are long dead. To borrow a line from Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.”

This summer, the future of our industry was arguably on display in the Anaheim Convention Center at SIGGRAPH, an annual gathering for people working in the field of computer-generated imagery. The exhibit hall was crammed full of dazzling technology and sci-fi spectacle: immersive virtual reality, photorealistic rendering of skin textures, skateboarding models in skintight mo-cap suits, fantastic creatures fabricated with exacting verisimilitude. Thousands of flickering and pulsing screens opened windows onto intricate and insubstantial worlds conjured forth from nothing but imagination and vast arrays of data.

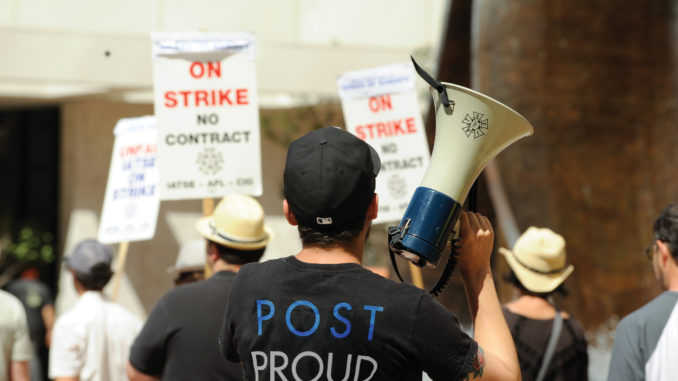

Toward the back of the exhibition hall, though, a steady stream of folks pooled around a booth without any flashy displays or animated eye-candy. The booth was for the IATSE’s nascent visual effects union, and the stream of artists and technicians who came there arrived with stories of months of seven-day workweeks and 16-hour workdays. They came to talk about economic insecurity, the crippling cost of health care and families with whom they could never spend enough time because of grueling schedules. They came to talk about how their talents generate fantastic profit for corporations, who regard the craftspeople themselves as disposable.

Acknowledging the presence of the past does not necessitate a facile equation between now and then. Nobody would suggest that these 21st-century pixel jockeys are identical to the children toiling in 19th-century textile mills. But their workplace concerns do represent a continuation of the old and unending debate over the nature of the obligations employers and employees have to one another. And, like all manner of employees before them, those working in the visual effects industry are coming to see that they need to stand up and stand together if they are to seek justice and security in their working lives. We may now be able to don headsets that plunge us into virtual worlds populated by computer-generated holograms, but, in the words of labor organizer and folksinger Utah Philips, “The past didn’t go anywhere.”

The fierce and sometimes bloody fight for a shorter workday and workweek is a thread that ran throughout organized labor internationally from the Industrial Revolution forward.

What this means for our celebration of Labor Day in this time and place is that, if you are working a union job and have Labor Day off, you should recognize that you owe your leisure to a long tradition of solidarity. Relish the leisure this holiday affords at least as much as you relish those hot dogs. It is a leisure that was hard-won through generations of folks banding together to demand time released from the demands of the workplace.

If you are working for a non-union employer, mark Labor Day by recognizing that collective action to improve working conditions is not simply a tradition relegated to history; it is a practice we must carry into the future. If you do not have a contract at your workplace, reach out to a union organizer to talk about how one might be won.