By Andrea Van Hook

The Matrix hit screens around the world in 1999 and immediately became a cultural icon. Rapidly developing a passionate following, the film inspired a game, Enter the Matrix, and a series of nine anime films by Japanese directors, called Animatrix. The series continued with Matrix Reloaded, which was released in 2003 and currently holds the record as the highest grossing R-rated film of all time, as well as the thirteenth highest grossing film in box office history. Matrix Revolutions, the third and final chapter, was released in ninety-five countries simultaneously on November 5.

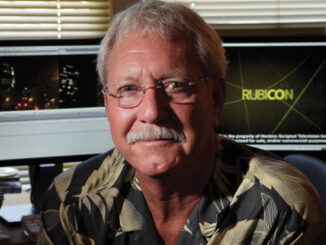

By an account, editing three high-profile, visual effects-laden movies over the course of four years is an incredible achievement, Having won the Best Editing Oscar for the original Matrix, Zach Staenberg discusses the pressure of editing such eagerly awaited films, how he handled the huge numbers of visual effects shots, and the challenges he faced.

CineMontage: How does it feel, having worked on such a successful film and the two sequels

Zach Staenberg: The Matrix movies are a true trilogy, not sequels. Larry and Andy Wachowski, the directors, envisioned all three of them from the start. They’re designed to be viewed and thought about as one continuing storyline.

What thrills me is the fact that millions of people have seen them. At the same time, even though the Wachowskis have this very commercial sensibility, it’s this really personal, idiosyncratic story. I feel so fortunate to be part of that. To do three movies and have them become, in some form or another, cultural touchstones is a real honor.

CM: The first movie was such a huge hit. Was there more pressure on the next two as a result?

ZS: To a certain extent there was. The Wachowskis didn’t want to make two more movies unless they could make them better. That’s one of the reasons that both Reloaded and Revolutions cost twice as much as The Matrix. You want to expand the universe and expand the ideas and give the audience more.

The Matrix contains ideas and themes that you don’t see in many other movies. Some people love the long dialogue. Some people criticize us for them. You don’t see them in a lot of other movies though. You also don’t see too many movies where someone is literally reborn. Neo comes out of the pod. It’s really a bold, exciting and brave scene. You’re putting yourself on the line to make things like that. One of the really great things about these movies is that they’re basically a studio version of an auteur film.

“Larry and Andy are very fond of mixing ideas and dialogue into the action. As the editor, my job is to blend the two seamlessly and keep everything as tense as possible.” – Zach Staenberg

CM: What’s your relationship with the Wachowskis, and how has it changed over the years?

ZS: Revolutions is the fourth movie I’ve edited for Larry and Andy. We started on Bound. And that’s when they first told me about Matrix. They had the script and they were hoping to direct it and they were hoping to make two more.

It’s been a long odyssey. Everyone has gone through all sorts of changes – marriages, children, deaths, births. We have a really close working relationship. I support them pretty much unequivocally, and they’ve been very, very supportive of me though this whole thing.

CM: Does one brother tend to be more focused on production and one on post-production?

ZS: No, they’re very symbiotic. When we made Bound, they had one parking place that simply said “Wachowski Brothers” and they would come in one car. They’re still very much like that. To me they’re distinct individuals, and I could go through each one’s personality, But that’s really not necessary, because when they are directing they are a cumulative brain.

CM: Were Reloaded and Revolutions shot one after the other or were they shot simultaneously?

ZS: They were shot in the way that made the most sense to production. If there was a location that was in both Reloaded and Revolutions, we shot it out, or if there was an actor who had only ten days work over both movies, we’d try to put those scenes together and shoot that actor out. Just like a production makes decisions on how to shoot a 120-page script, these were basically two movies that were like one, 240-page script.

As a result, I was editing both movies concurrently, with an eye to finishing Reloaded first.

CM: What was the size of your crew?

ZS: On a big project like this, you look for certain skills. I needed a great assistant on the Avid. I needed someone who has a lot of experience handling visual effects. I needed an overall great first assistant who really knows how to deliver a movie of this size, with all the demands. Within that, you want everyone to be able to move into each other’s area without any hesitation.

On the first Matrix, I had three assistants, and we had a fairly separated visual effects department. We had a visual effects editor and two visual effects assistants. Although it went very well, with Reloaded and Revolutions I wanted to integrate visual effects under editorial. So this time – bear in mind, we were doing two movies at once – I had seven people. Two were essentially dedicated to handling the volume of visual effects we had.

Personally, I like to have the smallest crew I can to comfortably do the job. Obviously you don’t want to tax people by being understaffed. But the more people are invested in the process, the more camaraderie there is, and everyone has a better work experience. Fortunately, Larry and Andy are very organized and they don’t create a lot of chaos, and that’s one of the reasons why I can comfortably edit these movies by myself.

CM: Did you have the same crew for all three movies?

ZS: There was a two year production gap between The Matrix and Reloaded, so only Catherine Chase was on all three movies. She became my overall first assistant on Reloaded and Revolutions, and Jody Rogers, who handled visual effects, was with us for those two as well

We started shooting Reloaded and Revolutions in March 2001 in Alameda, California, where we filled out the crew with local people, including Graig Alpert as the Avid assistant. That’s where we shot the freeway chase. We built the Oracle Park that is in Reloaded, and shot the burly brawl, which is the fight scene with all the Agent Smiths. And we built Zion, which appears in both movies.

I came back during the summer of 2001 to our editing rooms in Venice to edit the freeway chase scene and the burly brawl and turn them over to visual effects. It then took visual effects from August 2001 through February 2003 to complete that work, particularly the burly brawl.

We then went to Sydney, Australia in the fall, and while there Dave Birrell as my Avid assistant. Coming back here to Venice for the last 15 months, We replaced Dave and Ian Slater.

“The more economical you can be, the better off you are. Once you’re confident that your idea has been communicated, move on.” – Zach Staenberg

CM: Were people divided up in terms of working on film or on the Avid?

ZS: People have their specialties. Ian is clearly the Avid first. There are few who could beat him on that machine. There’s not too many more experienced than Catherine in terms of delivering film. But at the end of the day, they both did what they needed to do. Catherine has her own Avid and so does Ian. Jody Rogers and Rob Komatsu, who were handling visual effects, also had Avids. Catherine is the point person on film and the over all person, but you try to keep the flow as open as possible, so everyone feels like they’re working together.

CM: How did you handle dailies?

ZS: Everything was shot on film. We printed and screened dailies every day for 270 production days. We shot over 18 months because we took hiatuses both to edit and to just take breaks.

My assistants organized the dailies on film cutting order. We digitized the sound directly from DAT and we’d synch it in the Avid. I think that’s more accurate than synching in telecine, and it’s a job for assistant editors. We explored using a digital disk recorder, but when we started in the spring of 2001, the technology was too new, and our production mixer didn’t want to risk it.

CM: How many visual effects shots did you have in each of the movies?

ZS: About 440 in The Matrix, if I remember correctly. On Reloaded, we had around 1100 shots and on Revolution, 750

CM: How did you handle screenings?

ZS: On The Matrix and Reloaded, we screened several times on film. The first time I screened Revolutions, we ran an Avid output with a video projector, because so many shots are completely or mostly CG. In Reloaded, that wasn’t the case. Even though there were more visual effects shots, most of them could be screened on film in some form, often as blue or green screens. These were screenings only for the directors, myself, and the first assistants.

Take the freeway chase from Reloaded – the day I finished cutting it, it was totally screenable. That chase included 300 to 400 CG shots. But it was still a totally watchable sequence even before we turned it over to visual effects. But in Revolutions, the scene before the siege – there’s nothing there. There were lots of human elements that I would pick and cut, but you couldn’t really screen it.

CM: Is the rumor that there’s a 900 page storyboard encompassing all the movies just a rumor?

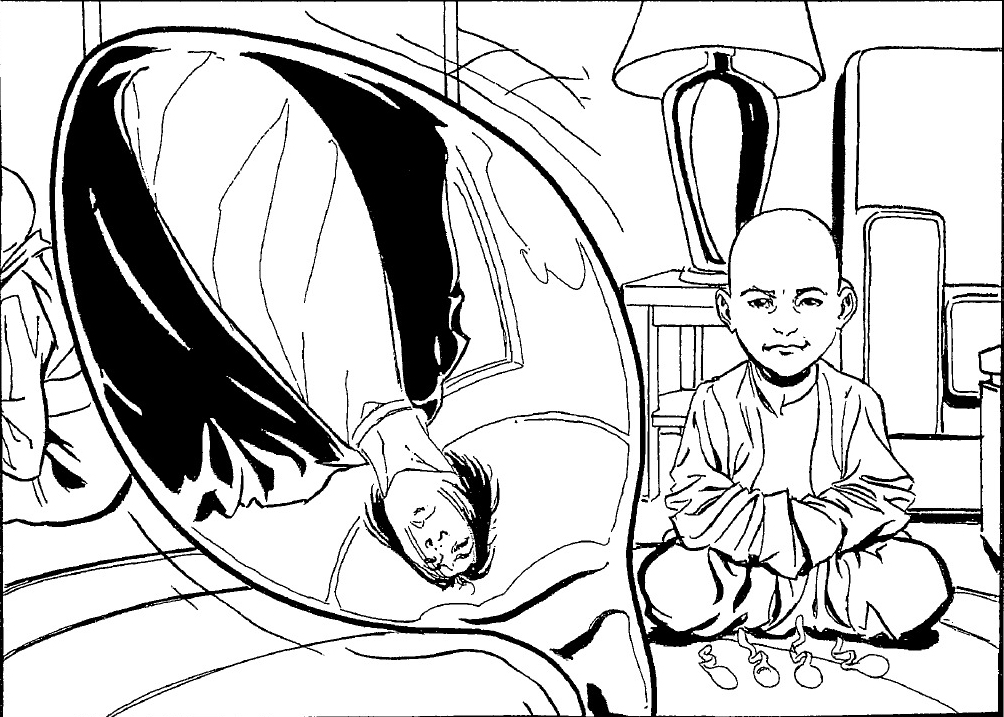

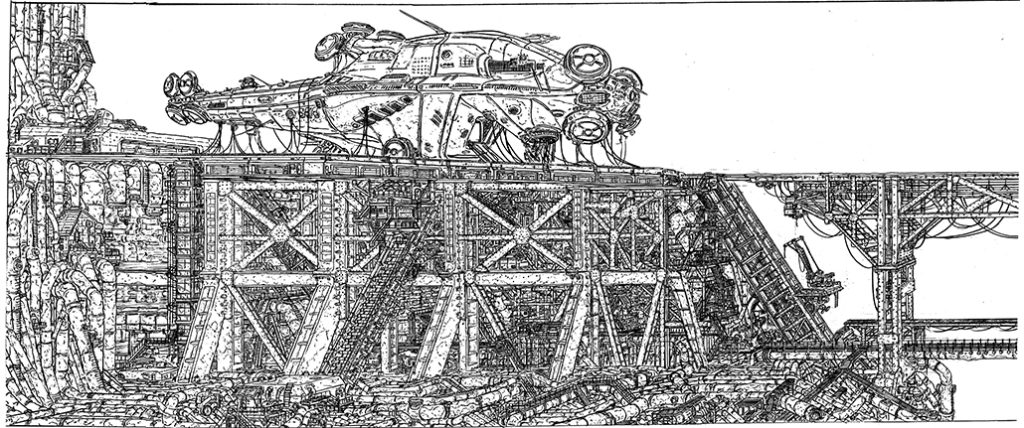

ZS: The Wachowskis didn’t storyboard the whole movie, just any scene that’s really complex. That gave Larry and Andy a bible of sorts that they could work from. They worked with Geof Darrow, a conceptual artist. He is to The Matrix what the Swiss artist H.R. Giger was to Alien. Geof created detailed drawings of most of the sets, He drew the APUs [Armored Personal Units], and he drew the inside of the ship Nebuchadnezzar. He drew the pods where Neo was reborn.

Take the shot of Neo rescuing Trinity in Reloaded. He swoops down to ground level, and catches her before she impacts the car. He comes up 60 stories to the roof where he’s going to pull the bullet out of her. Obviously there are a huge number of elements. Storyboards show you the angle, the camera lens, and how to make the shot.

Usually, I never look at the story boards while cutting. I just cut the film. But when sequences are pure CG like in Revolutions, I use the storyboards more carefully, because they’re telling you what you’re going to get from CG and where you should be going.

CM: What were the pre-visualizations? How were they used

ZS: Take, for example, the siege scene in Revolutions that starts when Mifune looks up and the dock ceiling starts to shake. A company called Pixel Liberation Front took the storyboards for that scene and turned them into animated sequences called pre-vises. Once they’re in the computer they can give me different angles. And so I actually have a ten-minute sequence that I edited entirely from the pre-vises. Based on that editing, shots are then changed as necessary or deleted. The pre-vis process cost money, but in a picture like this, it actually represents a savings, because we learned which shots were really needed.

CM: How much compositing did you do in the AVID?

ZS: We would do some of the simpler stuff here in the editing room, but I don’t like to do much rough compositing. We had a visual effects department and were constantly sending material back and fourth to various effects vendors. We would use these as starting points. Larry could look at the sequence and say I’d like to change that from a 21mm lens to a 27mm , let’s boom up a little bit, etc. And I could say, can’t we get a shot of this here, because we have to connect that, or let’s make sure that we get some overlapping action to smooth out a cut.

“The Architect has some really long speeches. I was cutting lines from one take to another. The idea was to create this very flowing performance from the best material, a performance that mesmerizes you.” – Zach Staenberg

CM: What was your interaction with the visual effects department like?

ZS: We were pretty close. John Gaeta, who was our visual effects supervisor, was in here all the time for the reviews. We’ve all been working together a long time now.

CM: What were you sending back and fourth? Did you have the Quicktime files?

ZS: We looked at effects on film and as QuickTime files, loaded into the Avid.

During the last several months, I went up with one of my assistants to work with our main visual effects vendor, ESC. We worked out a system that allowed us to take two Avids up there and, using high speed transfer, talk to Avids in Venice. Basically, it was like having another system down the hall.

When we started mixing at Warner Bros., we also set up an Avid there. So at that point, I could walk into Warner Bros., or here in Venice or up in Alameda and cut. It was pretty expensive, but we couldn’t have delivered the movie otherwise.

CM: What was it like working with so many visual effects?

ZS: Basically, you’re in production right up until the time the last visual effect is done. Even though we had a high degree of careful planning, the cut would change once we got a visual effect – from just a couple of frames to a more serious rearrangement of a sequence, because you’re finally seeing it for the first time. Very, very rarely would we just pop it in.

Adapting to this different workflow is the biggest change that we had to face. We were taking the shooting day and expanding it across the entire post production schedule.

CM: Did the technology of visual effects change from one film to the next?

ZS: A lot of people know how we did certain shots on The Matrix with an array of 120 still cameras. There were no still cameras on Reloaded and Revolutions. It was all computerized, all virtual. So essentially we did the same thing, but even better, with more control, more allowable movement. That’s a good example of how technology changed.

Some of the work we did in Revolutions, like the super punch near the end when Neo punches Smith, is totally virtual. Nothing’s photographed. That’s a virtual human. His face is in extreme close-up as it’s distorting. It’s an absolutely awesome shot.

CM: Has your approach to editing changed?

ZS: You have to recognize what the material needs to be. Hopefully that comes from a directorial point of view. You can’t edit The English Patient like you edit The Matrix. More than ever, I understand that the more economical you can be, the better off you are. Once you’re confident that your idea has been communicated, move on.

These are extremely dense movies. We do the opposite of spoon-feeding the audience. We don’t drop hints and carefully set up ideas and then pay them off. The Wachowskis will drop a very important idea into a sentence. If you miss that sentence, you have to go back and watch the movie again to get it.

I’ve always felt that editing is an extraordinary combination of art and craft. I really love well-crafted movies, but on large projects like these, it’s really easy to get side-tracked. At the end of the day, what makes editing an art is the same for any movie, even one that isn’t so technology intensive. I try very hard to keep that in mind as I’m editing, to make the craft serve the art. One of my last jobs as an assistant editor was working with Howard Smith on George Miller’s episode of The Twilight Zone, and George and I had several discussions about Road Warrior, which was out at the time and a movie I greatly admired. George told me that when the craft is there, the art can follow, and I really believe that.

“Some of the work we did in Revolutions, like the super punch near the end when Neo punches Smith, is totally virtual. Nothing’s photographed. That’s a virtual human.” – Zach Staenberg

CM: What were the most challenging scenes to edit?

ZS: The Architect scene in Reloaded was an incredible challenge. It’s a crucial scene. The Architect is the father of the Matrix. He tells Neo (Keanu Reeves) that he’s the sixth in a long line of Messiah-like figures, then presents him with a terrible choice. Essentially, what we learn is that when the program reaches this critical point, this cleaning out takes place.

I love Helmut Bakaitis’ performance as the Architect. He has some really long speeches. So I did a lot of work, sometimes cutting production lines from one take to another, using them like ADR. The idea was to create this very flowing performance from the best material, a performance that mesmerizes you.

The Oracle scene in Reloaded was also a challenge, because it has various levels. It starts simply. Neo recognizes her as a machine. She explains what these rogue machines and rogue programs are, and then builds into who the Merovingian and the Keymaker are. It’s like a musical piece that keeps building and building. It’s really quite beautiful, and I hope people see it that way.

Revolutions was a different animal. Because even though it has fewer CG shots, 90 percent of them are in the second half of the movie. The first half contained fairly traditional editing. We’ve set up this idea of Neo gone missing, but the audience sees where he is – in between the real world and the Matrix. The white train station scenes are very contemplative. There is still quite a bit of action – Trinity and Morpheus chase the Trainman into the Merovingian’s club where there’s a huge gun fight in the coat check. Smith shows up in the Oracle’s apartment, and in a disturbing way takes over the Oracle. As filmmakers, Larry and Andy are very fond of mixing ideas and dialogue into the action. As the editor, my job is to blend the two seamlessly and keep everything as tense as possible.

In the second half, it was a real challenge to keep a creative flow and do everything you could with material that didn’t yet exist. I was making picture changes right up until the last week of the mix, which we always knew we were going to have to do. We mixed Revolutions for about 65 days, including pre-mixes. We actually planned a pick-up scoring day into the schedule during the last ten days of the mix, because we knew we’d have to make music changes based on the new material. It was important to me to stay as open as possible and keep everyone in music and sound as open as possible, so that we could effectively handle whatever came in.

CM: If you had a colleague who was going to be approaching a similar project, what advice would you offer?

ZS: Every situation is so different. The Matrix films have an advantage in that they are, from the top down, very well organized. I think editors need to stay proactive. Interact with all the people who affect you, the visual effects people and of course the directors and art department. As you get raw material, try to use it. It’s a temptation to sit and wait until you get a shot that’s finished. But I think that’s a mistake. Staying as involved as you can will really help you understand a scene and how it’s going to flow and build.

CM: Did you have any budgetary concerns, or were you able to get what you needed?

ZS: For the siege in Revolutions, we had it all pre-vised out and I edited it together. We put it out for bids, and found out it was going to cost more than planned. So Larry and Andy and I sat down and we made a shorter cut for budgetary reasons.

Later on, we had a real concern that we weren’t going to get all the shots in time for our release. So we went through the movie and preemptively took out shots, and reedited scenes to see if we could make them work with less.

CM: Is there anything you would do differently?

ZS: On Reloaded I’ve heard all kinds of comments. Some people loved the movie, others like it but wished it was shorter, sometimes citing the freeway chase or the burly brawl. The Wachowskis got to a point where they were really happy, and they felt that their ideas were being communicated. I felt, listening to them, that unless those ideas were going to change, the cut was doing what they wanted. Sometimes, the director is asking you how it can play better for the most people. In this case, Larry and Andy were asking how it can play the best for their vision. It’s possible that we could have made a cut that would have worked for a slightly higher percentage of people. But it’s also true that a huge number of people liked it the way it is. It’s a mistake to try and please everyone.

CM: Did you have previews?

ZS: No. One reason we didn’t have previews is that no one was going to ask the Wachowskis to change anything. Everyone at Warner Bros. seems to respect the fact that these guys have a movie that’s going to go out. And they’re confident in it commercially as well. So there’s no question of trying to figure out if a character should be adjusted, or if we should shoot a different ending.

CM: Would you ever shoot this kind of project again?

ZS: It will never happen again. I mean this with all humility. It’s a once in a lifetime experience and I’m really grateful I was part of it.