Compiled by Jeff Burman, Christopher Cooke and Michael Kunkes

Editor’s Note: In celebration of the Editors Guild’s 80th anniversary on May 20, 2017, we reprint this story on the founding of the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors, the forerunner of today’s Guild, which originally appeared in CineMontage JAN-FEB 2012 in honor of the Guild’s 75th anniversary.

1927-1936

In the throes of the Great Depression, Hollywood was a notorious anti- union factory town. Central to these efforts was the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, conceived in 1927 by Louis B. Mayer, not just as a publicity extravaganza, but emphatically as a company union. In the years leading up to the founding of the editors’ first union, the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors (SMPFE) in 1937, there were a number of crucial events that laid the groundwork for choosing a union. The choice was pragmatic. Events leading up to the founding of the union made the choice a prudent one and clearly reduced the risk of contentiousness among the editorial community.

Hollywood studios imposed numerous pay cuts and lay-offs between 1927 and 1931. Soon after the inauguration of US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933, studios announced a stunning 50 percent pay cut. Screenwriters and screen actors, feeling betrayed by the Academy in its capacity as their bargaining agent, resigned and formed the Screen Writers Guild and the Screen Actors Guild, respectively. That year, the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE), a presence in Hollywood since 1908, struck Columbia Studios, hoping to win jurisdiction of sound technicians there. This led to a range of jurisdictional disputes. Much of Hollywood was in turmoil.

Hollywood studios imposed numerous pay cuts and lay-offs between 1927 and 1931. Soon after the inauguration of US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933, studios announced a stunning 50 percent pay cut. Screenwriters and screen actors, feeling betrayed by the Academy in its capacity as their bargaining agent, resigned and formed the Screen Writers Guild and the Screen Actors Guild, respectively. That year, the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE), a presence in Hollywood since 1908, struck Columbia Studios, hoping to win jurisdiction of sound technicians there. This led to a range of jurisdictional disputes. Much of Hollywood was in turmoil.

In Gerald Horne’s book Class Struggle in Hollywood, 1930-1950: Moguls, Mobsters, Stars, Reds and Trade Unionists (University of Texas Press, 2001), Edmond DePatie, a Warner Bros. vice president, is quoted, saying that workers at the time were “exploited en masse.” It was “not uncommon to work people as late as 11 and 12 o’clock at night” and “every Saturday night, 52 weeks a year.”

Guild members who eventually joined the SMPFE in the late 1930s agreed, referring to work at this time as “slave labor.” All of them readily endorsed the significance of the union, saying it applied welcome disincentives to the long hours that were rampant in post- production before 1937. In those years, it wasn’t uncommon for “cutters” and their assistants to sleep in their cutting rooms, hoping against hope for something called premium pay.

There were several unsuccessful attempts to organize film editors before the SMPFE was founded. One group,called Film Editors, was formed in 1934. Under the leadership of Stuart Heisler, president, and Frank Lawrence, vice president, the group had active representatives in practically every studio. They included Hugh Bennett (First National Studios), Harold Kern (United Artists), Irene Morra (Fox), Thomas Pratt (Warner Bros.), Paul Weatherwax (Pathé), Grant Whytock (MGM), James Wilkinson (Paramount), Frank Lawrence (Metropolitan), Archie Marshek (Film Booking Offices), Ray Curtis (Universal), Desmond O’Brien (Tiffany-Stahl), William Hornbeck (Sennett) and Arthur Roberts (Columbia). “It is believed the [Film Editors] will speedily spread its influence throughout the production end of the industry,” wrote an unidentified trade paper in 1934 in an article entitled ‘Edited By’ Club Makes Rapid Strides Forward. “The general and enthusiastic response, which has greeted the new organization since its recent inception, indicates conclusively the need for such affiliation for advancement of the calling and general improvement and education of the personnel.” Alas, not much else is known about this short-lived group.

Current Guild members also include technicians from crafts other than picture and sound editorial. Film laboratory workers, who were represented by Local 683, were chartered by the IA in 1929. (The lab workers’ local was ultimately merged into the Editors Guild in 2010.) But in the early days, the lab local was just as critical to the film industry as were the projectionists in times of labor strife. The lab workers struggled with rival labor organizations, and did their share in purging racketeers and fighting for a safe, productive workplace.

The National Labor Relations Act was signed into law in 1935, establishing the right of workers to join trade unions and bargain collectively. The Screen Directors Guild (now the DGA), formed in 1936, led a boycott of the Academy Awards ceremony. None of the guilds had yet been recognized as bargaining agents by the studios. The Academy, under the leadership of director Frank Capra, quickly got out of the labor relations business.

1937-1939

Hollywood’s unionization drive was given a boost on April 12, 1937, when the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the National Labor Relations Act, passed by Congress two years prior. The ruling forced the studios to recognize the unions for actors, writers and directors. By May 9, the Screen Actors Guild completed its first contract with Hollywood producers.

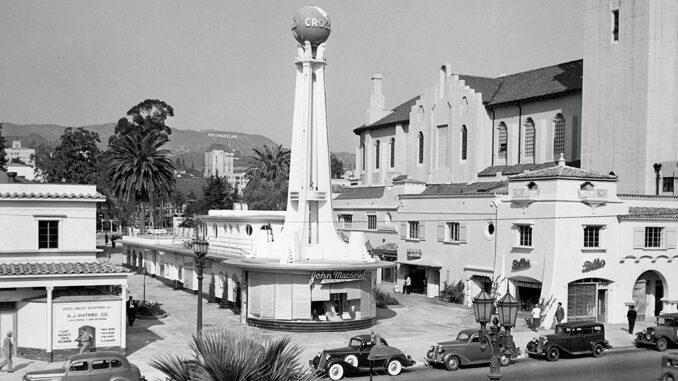

Photo: Bison Archives

On May 20, 1937, the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors was founded by sound editor James Wilkinson and film editors Ben Lewis and Philip Cahn. Four days later, the Society’s Board of Directors first met. At the third meeting of the Board on June 7, the initial slate of officers was elected: Edmund D. Han- nan, president; Frederick B. Richards, vice president; Edward Dmytryk, secretary; and Martin G. Cohn, treasurer. At that meeting, it was also decided that the Society’s offices would be located at 1509 Crossroads of the World on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. Society membership was a solid 571 men and women, encompassing picture and sound editors, assistants, apprentices and librarians.

By November 15 of that year, the organization ratified its first contract with the producers, increasing salaries and improv- ing working conditions. Feature editors now earned $100 a week, second editors (trailers and shorts) $75, and sound editors and librarians about $60. They each worked a 54-hour week over the course of six days, with time-and-a-half on Sundays and double time on holidays. Assistants and apprentices were paid an hourly rate, with assistants earning $1 an hour.

The Society moved quickly. In 1938 William Sharp was hired as the Society’s first business agent. A ten percent wage increase for picture editors was negotiated. Similar increases were won over the next seven years. Sound editors and music editors were recognized as separate entities with an established scale rate of $70 a week.

According to the Local 683 newsletter Flashes from 1939, the IATSE won its first closed-shop agreement on August 12 of that year. The producers promised to employ only members of the IATSE in ten of the locals it then represented: the sound technicians of Local 695, the film lab technicians of Local 683, the studio technicians of Local 37, the costumers of Local 705, the makeup artists of Local 706, the studio property men of Local 44, the studio grips of Local 80, the studio projectionists of Local 165, the studio laborers and utility workers of Local 727 and the studio chief set electricians of Local 728. Cinematographers were excluded because of a jurisdictional dispute, and the editors were not yet in the IATSE. This significant contractual gain was won during the term of disgraced IA president George E. Browne. Browne was linked to organized crime in Chicago and was convicted of extortion and conspiracy charges in 1941.

1940-1943

The SMPFE held its first dinner-dance at the Florentine Gardens in Hollywood on September 20, 1940. An early playground of the stars, the Gardens was known for its huge bar and dance floor, and lush floor shows. The evening was the result of the “social gathering” proposed at the Society’s June 6 Board of Directors meeting by MGM’s Fredrick Y. Smith, who was named head of the organizing committee.

The SMPFE held its first dinner-dance at the Florentine Gardens in Hollywood on September 20, 1940. An early playground of the stars, the Gardens was known for its huge bar and dance floor, and lush floor shows. The evening was the result of the “social gathering” proposed at the Society’s June 6 Board of Directors meeting by MGM’s Fredrick Y. Smith, who was named head of the organizing committee.

Very few recollections of the event survive, but something of the spirit of the evening is left to us in the form of a tattered copy of the impressive 72-page program book. Director Frank Capra, President of the Screen Directors Guild, wrote the Foreword. Praise for the editor’s craft came from people like director Norman Taurog, who said, “The finest jobs of film editing are those in which the editing is not apparent.” Director Dorothy Arzner, herself a former editor, said that editors were “in the only field that is a school for direction.” Producer and former editor Sam Zimbalist painted a picture of the harried film editor as set upon by everyone from the star to the writer to the director. And with tongue somewhat in cheek, Hal C. Kern, fresh from his 1939 Oscar win with James E. Newcom for editing Gone with the Wind, wrote of editors and assistants alike, “If we would count to five before springing some of our ‘great ideas,’ nine times out of ten, we would keep our mouths shut.” Sound advice from David Selznick’s film editor.

The program book included congratulatory ads from the likes of Jack Benny, Pacific Title and Art, Pathé Labs, Technicolor, Hal Wallace, Spencer Tracy, Hal Roach, Matt- son’s of Hollywood, Edgar Kennedy, Consolidated Film Industries, Bing Crosby, Clark Gable, Rita Hayworth, Hedda Hopper, Alfred Hitchcock and Groman Mortuary.

Nineteen-forty was a watershed year in other respects. Music editors were admitted to the Society as an official classification, editors in New York began working on forming their own Guild, John W. Lehners was hired as the Society’s business agent (a position he would hold until 1972, minus a two-year stint in WWII) and, perhaps most importantly, in February of that year, Society members gained a ten percent wage raise over the first contract with producers.

On January 1, 1943, the SMPFE published the first issue of The Leader, the organization’s debut bulletin and precursor to today’s CineMontage. However, Society president Fredrick Y. Smith of MGM seemed less than optimistic about the periodical’s prospects for success. “Out of approximately 700 members in our society, there are some who probably will not give two hoots for this sort of publication and who may not even be interested enough to read it…” Smith was astute enough, however, to know that the majority of members were “interested in the welfare of their society.”

Amid the reporting of increases for members receiving overscale pay and collections of wage claims was a great deal of concern about members who had joined up or been inducted into the armed forces. As of this date, 214 members were serving, a number that was soon to increase, “thanks to Tojo and Schickelgruber,” according to Bulletin Committee member Richard Currier. The Board, however, did its bit, cutting its meetings to once a month from every week in an effort to conserve precious tire rubber. Society members were well represented in many branches of the Service, including the Office of War Information in the nation’s capital, Astoria Studios on Long Island and at “Fort Roach” (aka Hal Roach Studios) in Los Angeles. Frank Capra headed a special unit with William Hornbeck commanding editorial.

Alas, this first Guild publication was not to last, and ceased publication in 1944 after just six issues, when the Society affiliated with the IATSE.

Speaking of the IATSE, editors on the East Coast followed in the footsteps of their fellow soundmen, cameramen and projectionists who had already been unionized by the IA, and formed their own union. The IATSE granted East Coast editors a charter in 1943 and Motion Picture Film Editors, Local 771 was born.

Meanwhile, the SMPFE made new advances in its collective bargaining agreement, adding a tiered wage structure, severance pay and expanded vacation pay.

1944

In 1944, Local 771 in New York elected Morrie Roizman as its first vice president, and Jack Bush as vice president. The same year, the young Guild negotiated its first union contract with the newsreel companies, calling for a closed shop, 40-hour workweek, paid vacation, time-and-a-half for overtime, a Service- man’s Clause and a minimum wage scale with industry equity. The following year, Charley Wolfe became the first business agent.

When the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors agreed to accept a charter from the IATSE in 1944, it was at a time in Hollywood when unions faced widespread jurisdictional disputes and attempts at consolidation. The IATSE was the logical choice. Having first established itself in Hollywood by representing projectionists in 1908, it had become an effective bargaining agent for many categories of film work. Many Society members believed that without the clout of a national labor organization, they would not be able to negotiate for better contracts.

It should also be noted that in 1944, three years had passed since a corruption scandal led to the conviction of two former IA leaders on racketeering charges, growing out of their close ties with organized crime boss Frank Nitti. All told, mobsters dominated the IATSE for seven years. Willie Bioff began extorting money, first from kosher butchers, then from Chicago movie theatre owners by threatening a projectionists’ strike. Bioff ’s success attracted the attention of Nitti, the successor to Al Capone. Nitti was soon skimming two-thirds of Bioff’s take. As if this wasn’t enough, Nitti fixed the IA elec- tion in 1934 and installed George Browne as IA president. The extortion racket expanded, with the major studios paying $50,000 a year for “labor peace.”

Organized crime’s influence began to unravel in 1941, when a top executive at 20th Century-Fox was indicted for tax evasion. As his fortunes plummeted, he implicated Bioff in a $100,000 “loan.” Browne and Bioff were eventually convicted on federal extortion and conspiracy charges. Bioff was sentenced to ten years in prison, Browne to eight. It was estimated that at least $2.6 million was extorted from 1935 to 1940. By 1944, these influences had been repudiated by the IATSE and the IA was determined to leave this disgraceful episode behind it.

Organized crime’s influence began to unravel in 1941, when a top executive at 20th Century-Fox was indicted for tax evasion. As his fortunes plummeted, he implicated Bioff in a $100,000 “loan.” Browne and Bioff were eventually convicted on federal extortion and conspiracy charges. Bioff was sentenced to ten years in prison, Browne to eight. It was estimated that at least $2.6 million was extorted from 1935 to 1940. By 1944, these influences had been repudiated by the IATSE and the IA was determined to leave this disgraceful episode behind it.

A number of offers were made to the SMPFE to combine with other Hollywood labor organizations. Most notable among them was an offer by the Screen Directors Guild, which would have included only picture editors. There were similar offers for music editors and sound editors. Those and others were turned down. When an offer was received from the IATSE, there was some dispute about who should be allowed to vote. Notices were mailed to active members, including 268 who were serving in the military overseas. Some wired the Society that they wanted to participate by mail-in ballot. A General Membership meeting was held on July 17, 1944 without them. Some 89 percent of the members who lived in and around Hollywood attended the historic meeting. The Society of Motion Picture Film Editors voted to become part of the IATSE by a vote of 446 to 119.

On August 2, 1944, IATSE President Richard Walsh awarded a new charter to editorial workers, and the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors became the Motion Picture Film Editors, Local 776. The membership stood at approximately 900.

For former Editors Guild president Stan Frazen, who joined the Society in 1942, choosing the IA was simple: The IA offered to take all editorial workers, not just the picture editors like the Directors Guild proposed. Splitting up the editors was not an option, according to Frazen. All of the members didn’t feel that way at the time. Dann Cahn (son of Philip, co-founder of the Society), who also joined the SMPFE in 1942, thought that editors might have done better with the directors, and that perhaps the assistants could have been brought in later.

“I think one of the reasons the Society voted to go with the IA in 1944 was all the young members,” posited Gerard J. Wilson, who joined the organization as a sound editor when it was founded in 1937 and, like so many others, enlisted in the Armed Forces during World War II. “There was a lot of new people working at the studios who never would have been able to get jobs if it hadn’t been for the war…and these younger people knew that joining the IA would stabilize their employment situation after the war ended. Because our memberships were on suspension while we were in the service, we had no vote on the merger. I think, though, that it would have happened sooner or later anyway.”

Cahn agreed with that assessment. “They had a vote of those who were here,” he said. “I was in the service making training films during most of World War II. When I came back, we were in the IA.” Music and picture editor Edward Haire, another 1937 alumnus of the society, noted that when the IA vote came, there was an unusually high number of women working in editorial because of the war. As a result, according to Haire, they played a leading role in selecting the IA.

When the Society was looking for representation by a national organization, and considering the IA, a jurisdictional struggle surfaced at the studios. Herbert Sorrell, a former prizefighter, and head of the Painters Union and the Conference of Studio Unions (CSU), began to draw together a number of different crafts and pressed for recognition. Soon, the painters were joined by cartoonists, office employees, machinists and the IA’s film technicians from Local 683. By 1941, the CSU already had won a contract for cartoonists at Disney, MGM and at Schlesinger Studios. In 1943, the set decorators joined the CSU and Sorrell campaigned for representation for them. The studios refused. The IA, already well established in the studios, began to feel the effects of its CSU rival’s efforts to compete for work. But while the CSU set decorators struck, IA members continued to work. Incidentally, the film technicians withdrew from the CSU in 1944, and returned to IATSE as they felt the IA was a more effective bargaining unit.

1945-1949

By 1945, the standoff between the studios and the set decorators boiled over into a series of heated confrontations. On October 5, nearly a thousand pickets in front of Warner Bros.’ Barham entrance in Burbank faced helmeted police with billy clubs and tear gas. Pickets overturned three cars in front of the studio entrance hoping to block strike-breakers. Three hundred police and deputy sheriffs from Los Angeles, Glendale and Burbank refused to let this stand. They dispersed the strikers, causing about 40 injuries. According to historian Dan Biederman, high-pressure fire hoses were trained on the demonstrators from the ground, and studio executives hurled nuts and bolts at them from the roof tops. The national media dubbed it “The Battle of Warner Bros.”

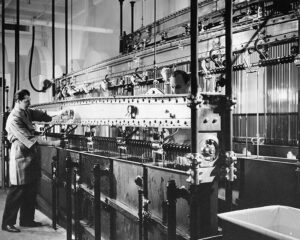

Photo: Bison Archives

After a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election in 1945, the IA gained the jurisdiction of the carpenters. In 1946, the CSU and the Carpenters Union sought a clarification of the NLRB election. The result was a lengthy impasse and lock out. But as the striking carpenters were arrested in greater and greater numbers, IA members continued to work. Some were bused in, others slept inside the studio walls.

In 1947, with the advent of the Taft-Hartley Act, the closed shop was outlawed and all union officials were required to take anti-Communist oaths. During this period, lay-offs became a reality at the Hollywood studios and seniority loomed as a big issue, and would for the next few years. By 1949, the IA won its NLRB election and the disputed jurisdiction with the CSU. The CSU’s support was undermined by arrests, lawsuits, poorly applied directives from the American Federation of Labor and by attrition.

As the decade drew to a close, it was evident that a new medium called Television had been developing rapidly and was on the rise. Fortunately, so were the salaries for Guild on-call editors. In 1945, the rate was $200 a week. By1949, it had risen to $305.72.

To be continued…