by Edward Landler

The Dede Allen Seminar Room at the Editors Guild offices in Hollywood was filled with the smells of Chinese dim sum on Sunday morning, September 17. The Guild’s newly formed Asian-American Steering Committee (a sub-committee of the Diversity Committee) hosted this traditional brunch, which was shared with a gathering of members from all ethnic backgrounds after listened to and shared experiences with a panel of distinguished Asian-heritage union members, who discussed their perspectives on diversity in the industry.

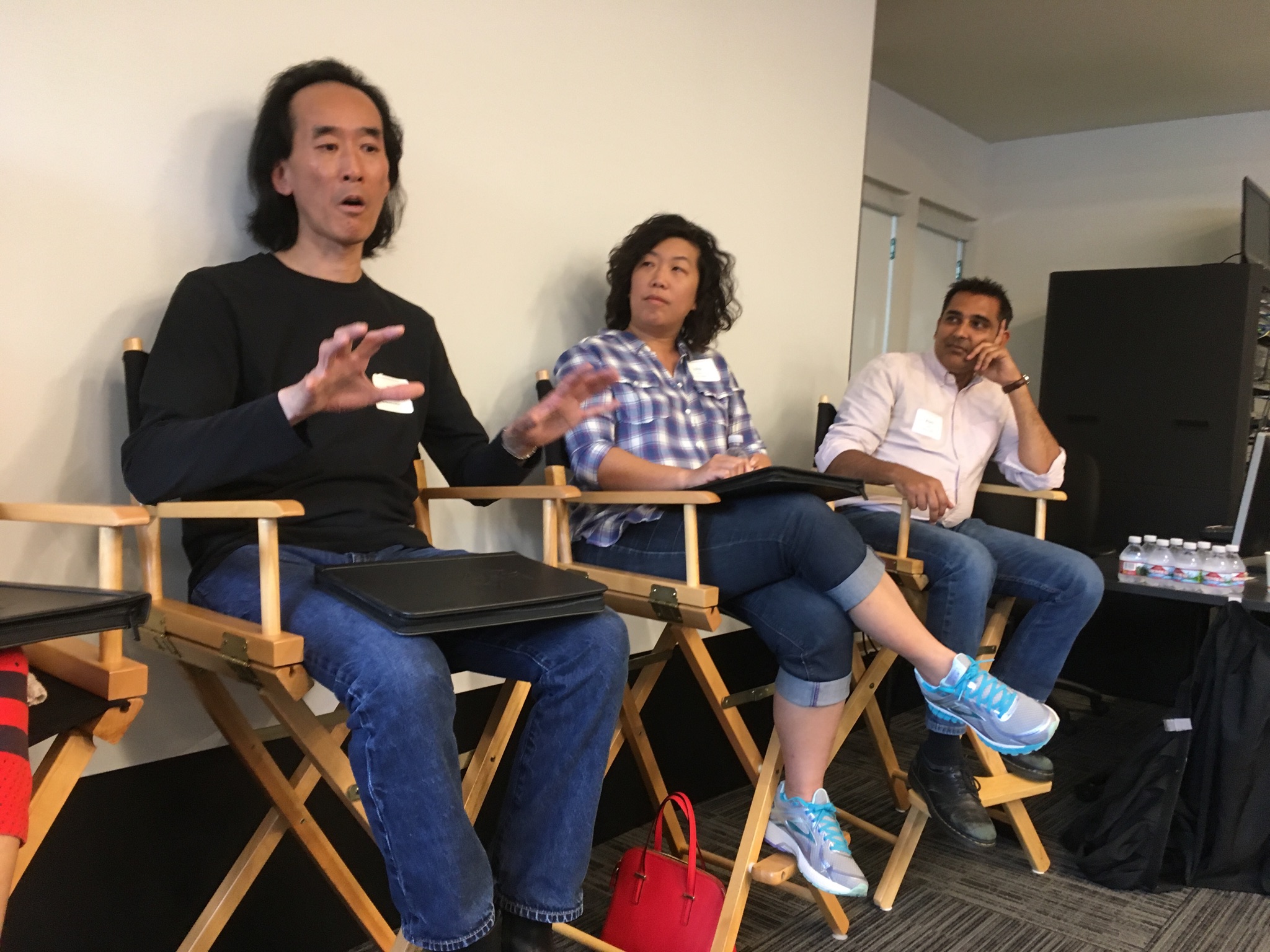

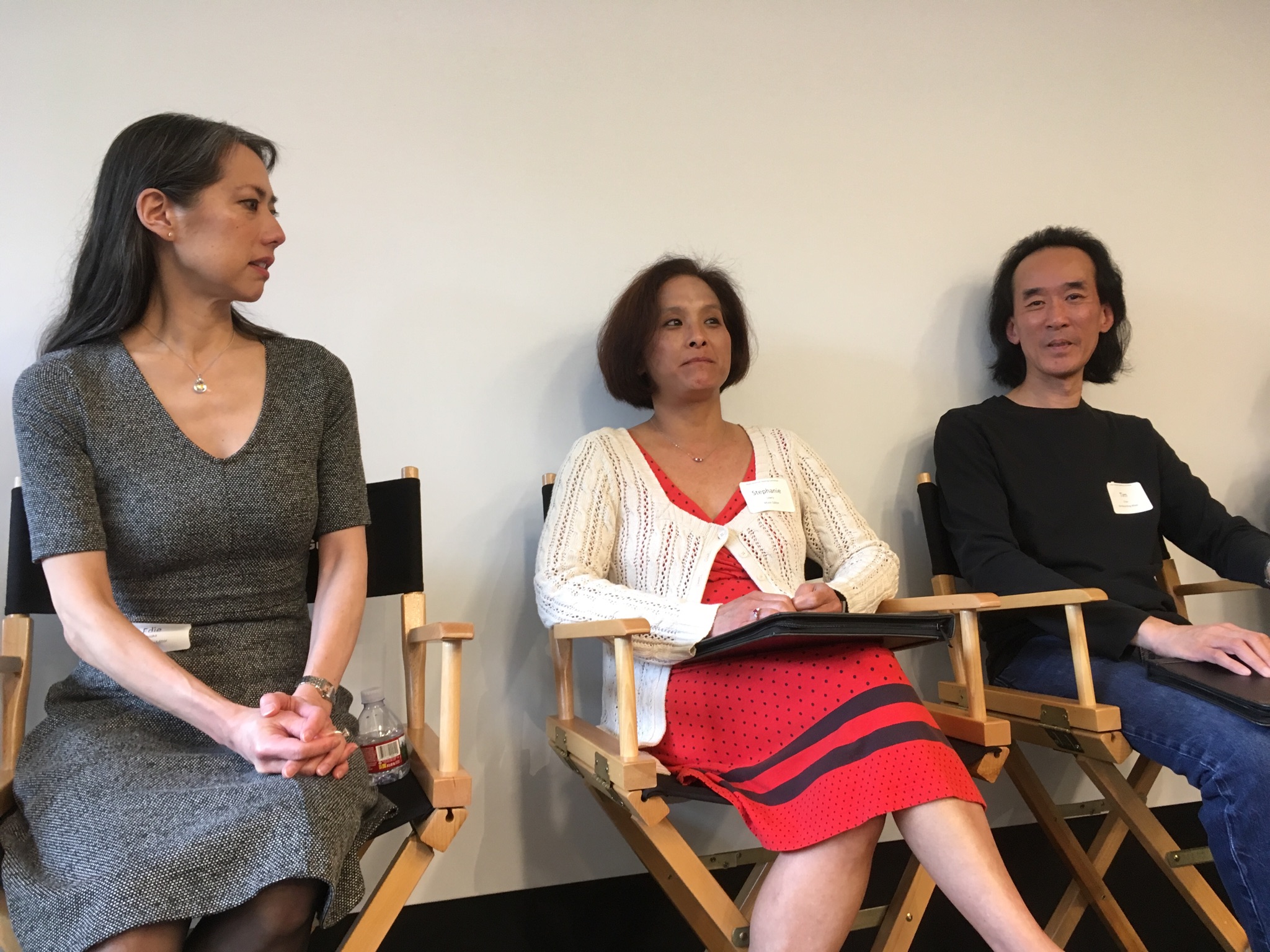

The panel members were:

Sound designer /supervising sound editor/re-recording mixer Tim Chau, MPSE (Kubo and the Two Strings, 2016; The Hangover, 2009; Home Alone, 1990).

Emmy-winning sound editor Don Hall — in a career spanning 66 years and over 70 credits in film and TV, he became Vice President of Post-Production at the Walt Disney Studios and is currently Professor of Sound and Post-Production at the USC School of Cinema.

Picture editor Edie Ichioka, ACE (The Boxtrolls, 2014; Murch: Walter Murch on Editing, 2007; Toy Story 2, 1999).

Emmy-winning music editor Stephanie Lowry (X-Men: Days of Future Past, 2014; Tropic Thunder, 2008; Spy Kids, 2001).

Assistant editor Asim Matin (Power Rangers, 2017; An Inconvenient Truth, 2006; Any Given Sunday, 1999).

Picture editor Julia Wong, ACE (Hercules, 2014; Extract, 2009; X-Men: The Last Stand, 2006).

Picture editor, Diversity Committee co-chair and panel moderator Maysie Hoy, ACE (Dolly Parton’s Christmas of Many Colors: Circle of Love, 2016; What Dreams May Come, 1998; The Player, 1992).

Hoy introduced assistant editor Ceci Hyoun, chair of the Asian-American Steering Committee, who asked audience members how many Asians they had worked with on one show. About two-thirds indicated they had worked with one Asian, about one-third with two, and only two people had worked with three on a single project.

“This is the first time for so many Asian-American Guild members to be in one room together,” Hyoun said. “To raise awareness of inclusion and diversity issues, you have to be willing to make yourself more visible. This is a means for us to voice our concerns more assertively.”

Beginning the discussion, moderator Hoy noted that she had wanted to go into movies from the age of four but, growing up in Vancouver, British Columbia, she thought all Chinese either worked in laundries, restaurants or groceries. She asked the panelists about their beginnings in the industry and the attitudes they faced in their families.

The 89-year old Hall said, “My parents didn’t know what the industry was, but I went to school wanting to be an editor. Around 1950, I started working as an assistant editor at a very progressive company, Mercury International, but rather than wait eight years to get into the Guild as a picture editor [the process then], I became a sound editor.”

Hall said that he and editor Don Chu were the only Asian Americans in the Guild, at a time when the best-known craft professional in the industry was the great, Oscar-winning cinematographer James Wong Howe, ASC.

Japanese-American Ichioka’s family’s attitude toward the movie business was “not an issue,” she said, and she feasted on classic films at Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archives. Early in her career, she hopped between editing live action and animation — “and it’s all blended together now.”

Growing up in New Jersey, Pakistani-American Matin had highly educated professional parents who encouraged his ambitions, and his first big break was working in New York with Merchant Ivory Productions. As a child, he was inspired by Terminator (1984) to be an editor, and he studied its cutting on his VCR, controlling the speed of the tape with the remote.

Lowry, raised in New York, related, “All Chinese children take music lessons,” which she said later helped her as a music editor, but when she received a scholarship to study film at USC, her first-generation American parents “assumed I wanted to be the next Connie Chung.” She got into sound working on music videos and, as her career progressed, managed to balance her career in sound editing — and later music editing — while raising her children as a single mother.

Editor Wong knew she wanted to be a storyteller at 11, but her Chinese-born parents refused to pay for her college unless it was for a career in law, medicine or engineering. Instead, she stayed on in their Philadelphia home to save money while attending Temple University to study in its film program. Her family began to accept her ambitions in her senior year when she won the American Cinema Editors’ ACE Student Editing Award.

Though inspired by Star Wars as a child, the originally Chinese-Australian Chau studied piano and wanted to be a recording engineer. After working as sound editor on 10 major Australian features (including Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, 1985), he came to Hollywood for a movie job that fell through. His restaurant-owner parents lent him money to tide him over until he found regular film work here. After returning home to be supervising sound editor on Quigley Down Under (1990), he came back to LA and remained to amass 70 more credits.

Steering the conversation to the awareness of diversity on the job, Hoy asked how Asian cultures who valued the needs of the group over the individual might lead Asian Americans to be regarded as “quiet” in work situations.

“Well, I am naturally quiet, but I speak up when I have to,” replied Hall. “I never really thought about it because there were so few Asian Americans when I started in the business.”

At USC film school now, however, he noted that, among the 60 cinema students altogether, there are 26 students from China “who always sit together and work together.” Born in the US, Hall speaks neither Mandarin nor Cantonese — “but they flock to me and I tutor them… I’ve encouraged them to speak and work with whites and other non-Chinese.”

Music editor Lowry offered, “I have a classic, quiet Asian personality but I rise to the occasion… I saw what people needed and fulfilled that but, when I wanted to move up, I had to promote myself.” Editor Wong added, “People react like it’s surprising that an Asian would be loud or funny or have opinions.”

Stating that it all comes down to one’s worth on the job, Hoy said, “Somebody once told me in an interview, ‘I didn’t know you were five-foot-one-inch tall,’ and I shot back, ‘I feel like I’m seven feet tall!’”

Nevertheless, the panel as a whole felt that being an Asian American had not held them back in their careers, but they all found that the issue of diversity manifested itself in subtle ways on the job. “Diversity is always on my mind,” Ichioka said. “People approach you as if you’re the spokesperson for all Asians.”

The others agreed and spoke of working on shows with one other Asian, and people consistently confusing their names. Assistant editor Matin believed it was assumed that, as a South Asian, he was good at running computer systems. Hired on a show produced by Israelis, he mentioned that he was a Muslim and was told, “You know what you’re doing; you have the job.”

Bringing up a related diversity issue, Wong explained, “It’s hard to separate reactions to me as a woman versus being Asian… Being Asian and a woman fit more into being accepted as an assistant editor; when I moved up to editor, I wasn’t regarded as such a natural fit.”

Ichioka, Lowry and Hoy all told of being asked in interviews about having babies and raising children, questions that a man seeking the same job would never be asked. Hoy also remarked on the gradual changes in sexual attitudes: “When I was starting, working with Bob Altman and all those guys, you could sue them for sexual harassment at any time, but I took it as a joke. Like you said earlier, Tim, ‘You cannot walk into a room like you have a chip on your shoulder.’”

Chau replied, “No question, it’s tougher being an Asian and a woman than being a guy.”

Ageism as a diversity issue was also addressed when Lowry pointed out, “It happens a lot more now for those of us who came up when the industry was still film and not digital.” For Matin, as an assistant editor, the difference in film was that “you could switch places and learn more. [Editor] Richard Halsey, he was over my shoulder and telling me what to do.”

Hall recalled, “We looked at the film, studied it and decided where to cut…and you didn’t have to have all the sound for the first editor’s cut; directors and sound editors could still imagine what could also be there. With digital, kids don’t think about where to cut; they do it and right away can try something else.”

With the conversation turning to the changes in the workplace, Hoy said, “They think, ‘I can work on a computer, I can edit.’ They’re not learning how to tell a story. We’re more isolated; assistants are becoming just data wranglers. With Altman, we had a lot of fun and knew when to be serious. With dailies, you had to sit with the director and the crew and you had bonding.”

“Now it’s like a football team not huddling before the play,” added Ichioka.

Noting that she doesn’t go on location to cut anymore, Wong explained, “I’m in the cutting room all by myself and maybe get a text from the director now and then. In post, it takes five or six weeks to get to know the director.”

Before opening up the discussion to the audience, the moderator asked the panelists for their work and career philosophies. Hall responded, “Start early, have a plan and don’t be afraid to change your goals if you’re not happy.”

“You’re always worried about the wrong things,” said Ichioka. “You shouldn’t have to ask, ‘Why didn’t I just enjoy myself?’”

Lowry urged, “Don’t wait for what you want. You have to make yourself go for what you want.”

“You have to have a balance,” Chau stated. “Do your work and do great work and be yourself.”

“In terms of diversity, it’s not just a human story; if it’s a Black story or a woman story, you want the perspective of a Black or a woman,” Matin concluded.

Earlier, Hoy had spoken of her work on The Joy Luck Club (1993): “The stories in that movie were so personal to my life, I brought a sensitivity to it.” Now she warned, “Beware of typecasting. I’ve edited Black comedies. I don’t want to hear, ‘She only edits emotional woman Asian movies.”

After that, the audience joined in, sharing work experiences of assumptions being made about their abilities, as well as the difficulties of getting Asian stories produced and of Asian-American actors, writers and directors developing fuller careers. Despite Masters of None (2015-present) and other shows, Matin pointed out, “That’s maybe three out of 700.”

In response to observations that apprenticeships have disappeared with possible jobs for newcomers going to experienced assistants, Ichioka said, “Sometimes a person can come into tasks that can be considered apprenticing.” Assistant editors Halima Gilliam and Sharon Smith Holley noted that there have recently been job openings in which the less experienced could learn. Hoy noted, “We’re trying to change the descriptions to make that more possible.”

Finally, Filipina-American editor Tricia Rodrigo asked about getting around industry nepotism and developing networking. Ichioka told of working for free and learning on the job when she could find “someone desperate enough to accept me.” During his first year looking for work, Matin said, “I wrote 600 to 700 letters and got a three to five percent response rate. Now you can try to contact people whose work you respect through Facebook.”

As panelists and attendees broke up into multiple conversations over delicious dim sum, CineMontage sought out reactions to the fast-moving, two-hour discussion just ending. Panelist and steering committee member Lowry expressed hope that “this event would also foster a spirit of mentorship,” while fellow committee member Gilliam was delighted that “the panelists themselves were from so many different Guild classifications and of so many different origins and ages.”

Regarding their varied backgrounds, assistant editor Dov Samuel, born in Toronto to a Jewish family that had lived for centuries in India, said, “There were a lot of really good role models [on the panel] for the younger members. They shared experiences that don’t belong to any single minority group; I recognized the family pressures they talked about.”

Diversity Committee member Kathleen McAuley said, “I think that the diverse groups support one another and we learn from what’s different in our experiences.” Chinese-American assistant editor Shin Peng observed, “I loved hearing all their stories and seeing that it’s not necessarily a minority issue, but about starting out and getting on in the business.”

Meanwhile, with their appetites for Chinese cuisine and knowledge from experience satisfied, the audience members left to continue their careers in the film industry — perhaps foretold in the fortune cookies that came with the dim sum.

The Asian-American Steering Committee members are Anisha Acharya, Emily Chiu, Rahul Das, Halima Gilliam, Sharon Smith Holley, Maysie Hoy, Ceci Hyoun and Stephanie Lowry.