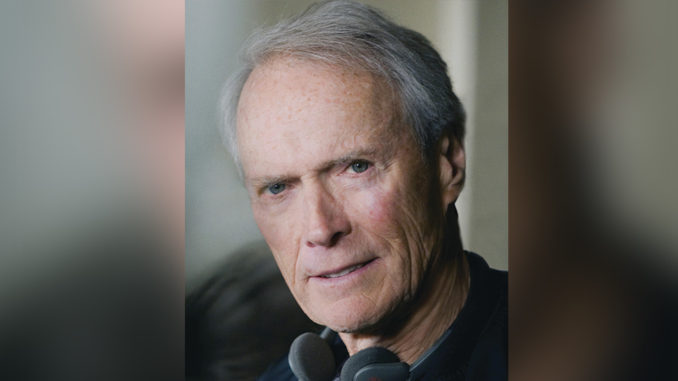

by Michael Kunkes

Clint Eastwood has a fondness for editing––and editors. According to the filmmaker, he has worked with only a half-dozen editors in the 38 years he’s been directing motion pictures, starting with Carl Pingitore, who passed away in January 2008. The two met on Don Siegel’s 1971 film The Beguiled, and Pingitore edited Play Misty for Me, Eastwood’s feature directorial debut, that same year. It was the only film they did together.

In 1972, three-time Oscar nominee Ferris Webster edited John Sturges’ Joe Kidd, which starred Eastwood. Beginning with High Plains Drifter (1973), Eastwood and Webster collaborated on a run of 14 films that ended with Webster’s retirement after Honkytonk Man (1982, co-edited with Michael Kelly and Joel Cox). Editor Ron Spang also worked with Webster on a couple of Eastwood films, Firefox (1982) and Any Which Way You Can (1980).

“Ferris was one of the all-time characters; he was great fun and a very talented editor,” Eastwood recalls in an exclusive interview with CineMontage. “Joel was Ferris’ film assistant before he became his co-editor. Ferris would be working on his Moviola with a cigarette hanging from his mouth, literally standing on a piece of film that unrolled onto the floor.

“Joel would be fixing rips and tears and picking up trims from the bottom of the bin,” Eastwood continues. “After Ferris retired, Joel became my editor and now he’s co-editing with Gary Roach, who is a terrific editor as well.”

“A movie is like a clay statue and editorial is the final part of that molding. It’s where a film evolves from a story that’s been read on paper and makes the transition back into a story again, only this time a visual one. It’s one of the most important processes of filmmaking.” – Clint Eastwood

Asked about Cox’s 30-odd years working with Malpaso, Eastwood’s Warner Bros.-based production company, the director simply states, “I just think that when you get people that are really good at their jobs, it’s tough to look beyond. Joel is totally on the ball, and a loyal person to work with. He’s taken me from the Moviola to the KEM and finally to the Avid––and he always keeps up on technology.”

On the importance of editorial, Eastwood offers, “A movie is like a clay statue and editorial is the final part of that molding. It’s where a film evolves from a story that’s been read on paper and makes the transition back into a story again, only this time a visual one. It’s one of the most important processes of filmmaking.”

Eastwood was compelled to return to acting for his current release, Gran Torino, even though he had not appeared on screen since 2004’s Million Dollar Baby. “I liked the story and the relationships between the characters and thought it had a really interesting script [by Nick Schenk; story by Schenk and Dave Johansson]. The guy in the story, Walt Kowalski, is exactly the same age as I am and, also like myself, is a Korean War veteran. I liked him because I saw him as someone who was set in his ways but could also change and evolve throughout the story. For most of my career, I’ve been an actor who occasionally directed. Of course, Europeans consider me more to be a director who occasionally acts, and that’s probably more true today.”

How does Clint Eastwood the director think audiences will receive Gran Torino? “By the time you’ve finished a film and lived through the editing and post process, you have no idea at that point if anyone’s going to go see it,” he says. “You can never guess what people are going to like. I don’t make movies for their commercial possibilities; I’d hate to be driven by that. I always look at a story when I read it and ask, ‘Is this something that I would like to see?’ Secondly, I ask myself if it’s something I’d like to direct or would like to be in.

“Once those questions are answered,” he concludes, “you just go ahead and make the film. Whatever life it’s going to have needs to have somewhat of the hand of fate on it.”