By Michael Kunkes

In the parking lot of LA’s Shrine Auditorium, it is the final rehearsal for the 59th Creative Arts Emmys, to be held the next evening, September 8. In the production room of the remote truck––a cramped space not much bigger than a Humvee––director Chris Donovan sits in the front row before some five-dozen monitors, flanked by technical directors Beth Stiller, working the switcher, and screens TD Rick Edwards, along with associate director Laura Lyons. With relaxed yet intense focus, the crew progresses methodically, item by item, through a paper script hundreds of pages long. Working with the crew onstage, the team goes through the timing for every transition, camera cut, wipe, pre-loaded effect, graphic, super and taped sequence as stand-ins stroll to the podium to accept imaginary awards.

For Stiller, it’s just another day at the office. Technical directors, one-time members of the Cinematographers Guild Local 600 (then 659), joined Local 700 (then 776) in the early 1980s. The Editors Guild is the appropriate affiliation for these craftspeople, for no other editorial position has so much split-second pressure riding on it, nor a smaller margin for error. Whether a sports event, live music performance, game show, reality show or taped sitcom, the TD, also known as the “vision mixer,” is the last stop, the final arbiter of what goes live on the air or live-to-tape.

The position of technical director goes back to the first generation of live television, when they were known as crew supervisors. They set up the show, put together the crew and saw that each member knew what he or she was supposed to do; and ensured that the cameras were properly positioned with the right lenses, that cabling was measured and in place, and that each camera cut was rehearsed. Then, the show ready for air, they would operate the primitive switcher in the control room (and later, the remote truck).

Gregory Schwartz

More than 50 years later, the job remains titularly the same, but the digital age, high definition, the proliferation of equipment manufacturers and the sheer scale of today’s entertainment and sports programming has made the job as it first existed almost unrecognizable today. While TDs are still looked to for crew leadership and a smooth-running show, changes are coming furiously.

“We babysit the grammar of transitions and are the gatekeepers of the video,” says Stiller, a veteran TD who represents the classification on the Guild’s Board of Directors and has won two Sports Emmys (XIX Winter Olympics, Games of the XXVIII Olympiad) and three Los Angeles-area Emmys (1999 L.A. Marathon, 2000 Rose Parade, 2000 KCAL Fight Night Live). “None of the video will go out to the record machines or to air unless we let it out.” However, according to Stiller, the technical director’s job has grown a lot more, well, technical.

“Switchers are way more sophisticated, and many more sources than ever before are being driven by the technical director,” she continues. “The switcher is also interfaced with other devices such as digital disc recorders (DDRs) that will play back different effects frames accurately. Over the last 10 years, manufacturers have been competing for the marketplace and we have had to keep up with the technology, so we have had to take it upon ourselves to learn all of this.”

Other industry jobs have not evolved in the same way, according to Stiller. “Directors still carry pencils and stopwatches, but our tool has evolved into a really challenging piece of equipment: a computer,” she explains. “But something that hasn’t changed in any TD job is that the entire crew has to work as one organism, and each part of the organism has to pull its weight. We’re only as good as our weakest link, and a fantastic synergy occurs when everyone is on top of his or her game.”

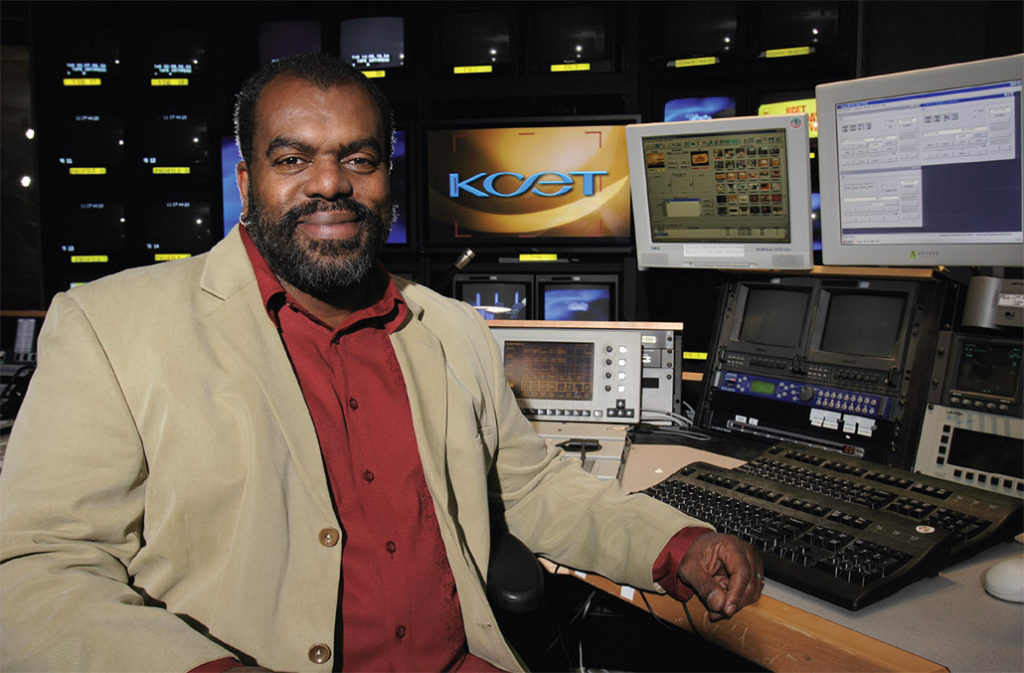

“A crew is a collective formed to do quality work,” says J.J. Jackson, aka Jonathan X, a TD and director who has won four Sports Emmys for his work on Fox NFL and NHL telecasts. He currently directs The Tavis Smiley Show on PBS. The best thing that has happened to TDs, he says, is that they now receive full credit alongside directors and producers––a trend that started five years ago on Monday Night Football. Along with that recognition has come a lot more complexity in terms of what the TD has to oversee.

“The technology is much more software-based and much more complex in terms of multiple menus, more virtual instead of physical routing, switcher interface with DDRs, high-end graphic character generators, sound, etc.,” he explains. “It used to be ‘Cut, dissolve and mix’; what used to be 50 to 100 parameters in a show can now be as many as 400.”

Robert Ennis, another TD as well as director, is the winner of a daytime Emmy for Hollywood Squares. After 12 years at ABC and six at CBS, he was hired by switcher manufacturer Grass Valley Group and spent 11 years as a teacher, trainer and writer (and still freelances for the company). He was instrumental in developing software for Grass Valley’s 3000 and 4000 series switchers, and owns patents for some of the bells and whistles on the company’s Kalypso switcher, one of the industry’s current standard bearers. A fixed-wing and experimental helicopter pilot, Ennis makes his home in Nevada City, California, and commutes to Los Angeles for his technical directing work on Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy.

He doesn’t play games though, when he talks about where the job of the TD is going today. “The TD has become more of a computer programmer than a crew supervisor,” he claims. “Everything is done with E-mems, which are basically timelines and snapshots of a show’s events, all of which require a lot of programming time.” This level of complexity has made the job of the TD even more critical, according to Ennis, who adds, “I know it messes with directors’ egos when I say this, but when the director calls for a camera cut, it’s really just a suggestion. The TD is really the one flying the plane. That is not to say you’re going to override the director, but when, for example, he calls for camera two and camera two didn’t rack focus in time, a good TD will wait that extra beat to let that camera get in focus.”

“The market is progressing to the point where everyone is going to have his or her own TV station at home,” – Bill Irwin

The bottom line, Ennis says, is that directors can sometimes make a mistake––but there’s nothing between a TD and the final transmission. “A ‘zero tolerance job’ is what my TD friend Wayne Parsons [Entertainment Tonight] used to call it,” he says. “You are required to be at your best at all times, and an absolutely perfect job is the minimum of what is expected of you. The best you can do is not to make any mistakes. There’s no rewind or fix button anywhere.”

“There are ballplayers making millions of bucks who are hitting .220,” says Jonathan X. “However, at any level, a TD needs to bat .950 and higher, because every cut, every keystroke, every motion has to have a certain synchronicity to it. If the wrong cut or wrong trigger is made––or the wrong button pushed––everyone will see it. As far as I’m concerned, it’s one of the most underappreciated jobs in the industry.”

Speaking of sports, Stiller adds, “Now that switchers are highly programmable, a major challenge is to design the set-up to randomly access most efficiently, in the minimum number of keystrokes, instantaneous recall of any scenario. In live sports for example, we must be ready go from game play––with all it’s associated effects and graphics––to the shot of a hero or a goat followed by replays or a hero package, statistics, promos, a bumper sequence to commercial break, or back to the next game play. The best TDs solve the puzzle most ergonomically, appearing to hardly move while accomplishing the task. There is only one right button at any moment in time.”

Richard Wirth, a two-time Emmy winner (The Rachel Ray Show, 2006, and Sesame Street, 2005) and New York-based technical director, provides an example of the TD’s grueling preparation for each show. Wirth, who has TD’d PBS’ Live From Lincoln Center and Great Performances, relates the story of the production of a live-to-tape performance of the Broadway musical Fosse. “I worked with former Broadway dancer, now director, Matthew Diamond, who spent months breaking down the performance into some 1,500 numbered shots. When that’s done, we’ll tape a couple of performances and there will be extensive camera meetings that can last six hours a day between tapings.

“We babysit the grammar of transitions and are the gatekeepers of the video… None of the video will go out to the record machines or to air unless we let it out.” – Beth Stiller

“The TD has to listen to the score reader for the musical counts, as well as to the associate director for the selection of the next shot coming up, and to the director to take the shot at the precise moment,” Wirth continues. “The cameramen are receiving their computerized shot rolls so that they are ready for each upcoming shot. It’s total concentration and it doesn’t get more intense than this.”

There are plenty of changes coming in the newsroom too, including new equipment that may someday relegate either the director, associate director or TD to the scrap heap. For example, Grass Valley Group’s Igniter or Ross Video’s Overdrive Production Control System are touchscreen systems that extend the technical director’s reach to include all devices in an on-air production control room––including video servers, DVE effects, VTRs, DDRs, audio mixers, robotic cameras, teleprompters, graphics, routers, still stores and, of course, the switcher.

Comments Stiller, “A TD or director can move item numbers around, kill them, swap them and just point to the screen to launch the next event. And there’s just one person doing that, so it’s possible that either the TD or the director will disappear in the newsroom. In fact, it’s already starting to happen.”

Over the last few years, the latest bugaboo for TDs has been HD, which is still going through the growing pains of mixing multiple formats, despite its proliferation. Bill Irwin began as a technical director on sitcoms such as Alf and Roseanne, but switched to sports when film began taking over the sitcom world in the mid-1990s. Irwin was instrumental in organizing the Los Angeles sports community into the IA and convincing key employers to sign union contracts in the early 1990s. He claims that HD is still a myriad of different formats and aspect ratios.

“There are so many formats in which producers want their shows delivered,” he says. “ABC or Fox may want 720p, others may want 1080p. Producers bring in 4:3 NTSC tapes and ask you to put HD wings on them––so you can waste an hour a day just doing barn door wipes. It would be great if the government would just come in and say, ‘Put everything in 1080p and that’s your format.’ But frankly, the FCC has no interest in doing that, and it suits manufacturers to have multiple formats.”

“You are required to be at your best at all times, and an absolutely perfect job is the minimum of what is expected of you. The best you can do is not to make any mistakes. There’s no rewind or fix button anywhere.” – Robert Ennis

“If everyone was watching in HD, we’d have no problem with format conversion,” Ennis adds. “And from a pure switching point of view, it doesn’t matter what the format is; you’re gong to switch whatever the director calls. Fortunately, a couple of manufacturers are starting to come out with switchers––such as the Snell & Wilcox Kahuna––that are multi-format, because they see the migration and they know that people aren’t going to stop doing SD on Friday night and go to all HD on Saturday morning. But from a TD standpoint, it’s just another input source to deal with.”

HD has prompted some new thinking in the way TDs cover a show. In the instance of Jeopardy, a game show mainstay for three decades, the familiar tight set had to be completely redesigned and spread out for the vagaries of the 16:9 format. Ennis relates that although the show is now produced in the letterboxed format, it has to be shot to satisfy both camps. “With the new set, you can easily tighten up for a close-up, but most of our audience still watches in standard definition. So we have to shoot in HD, but still protect the 4:3; if the set hadn’t been redesigned for HD, you’d end up with parts of other contestants in the close-ups.”

“HD is phenomenal, not only the quality of the resolution, but also the monitors,” says Jonathan X. “The only thing I don’t like is the trend of upconverting everything and protecting the 4:3 ratio at any cost. I am a true proponent of HD, and feel that anything that is shot in HD widescreen should be shown in letterbox on SD channels. The popular argument is that when people see the black on top and bottom of the HD image, they will think they are losing part of the picture. That argument is old and dated, and should be thrown out. Show it in letterbox and truly use the full frame for composition. People will get used to it.”

The increasing sophistication of the job has prompted a shakeout in the ranks––not unlike that which followed the introduction of non-linear editing for picture editors in the 1990s. More and more TDs turn to directing or retire. “They’re having a tough time out there finding new TDs,” explains Ennis. “Part of the reason is that the role of the TD is diminishing to one of only being tied to a switcher. More and more productions want the kind of 3-D effects that you can’t create fast enough in a live environment, though manufacturers are working on it.”

Irwin, winner of a 1992 Sports Emmy for The 1992 America’s Cup and another this year for The Pokerdome, adds, “The TD is invaluable when it comes to quality, large-scale productions, but it’s a changing business. A lot of TDs are in their 40s and 50s and there aren’t a lot of new people coming into it. The job has become so potentially intimidating that a lot of people who would have gone into it 10 to 15 years ago won’t go near it today. The technology changes so rapidly that today we have to be proficient on five or six different switchers. People are holding onto their jobs, but eventually will retire. Who is going to take their places?”

Wirth has a different perspective. “There’s so many more venues and avenues where switching is a part of the production and people are getting trained all the time on new switching equipment,” he says. “I come from more of an engineering background, and TDs from my generation would go out, work with a crew and set up an entire event. Now, it’s mainly becoming a switcher operation, where a lot of the traditional responsibilities are carried out by a tech manager outside the control room.”

“I’ve known a lot of camera operators who’ve tried to become TDs,” says Ennis. “They get tired of carrying the cameras up and down stadium steps; they want to become TDs so they can sit down all the time. Those people don’t necessarily make good TDs. However, some of the better ones that I’ve seen come into the market in the past 10 years have come from the graphics side. Maybe that is where the new people will come from because there is a certain amount of creativity involved that you don’t get from other television disciplines.”

“The market is progressing to the point where everyone is going to have his or her own TV station at home,” Irwin adds. “There are switchers coming out now [such as NewTek’s TriCaster] that you can carry in a backpack and run off a PC. They can import video, instantaneously cut, do playback, effects, etc.––even output directly to the Internet. That may be the future for high school football coverage, but producers will always need those high-end trucks for the big game.”

Jonathan X offers the best piece of advice to people looking to fill the vacant spaces: “Work with your equipment, play with it, experiment with it. And if you are fortunate to be in a facility where you can play after hours, take the time to do it. And most importantly, never let the pressure of the control room reflect in your fingers. The truth is, technology can eventually try to take away everything, but one thing it can’t take away is the human emotion and spirit of capturing the event as it’s happening live.”