by Rob Callahan

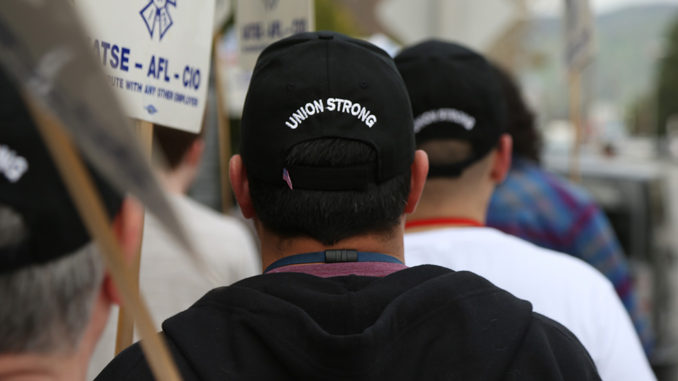

In recent months, the IATSE has made dramatic progress in bringing more work in unscripted television under the coverage of union contracts. Dramatic progress often demands dramatic struggle. Many employers prove fiercely resistant to signing union contracts, relenting only after employees exert pressure through bold displays of solidarity — including, in some cases, work stoppages. As those who follow our union’s organizing activity know, the IATSE makes regular and effective use of recognition strikes, in which employees halt all work in order to compel their employers to sign union contracts.

But many of the gains the IATSE has achieved in reality television of late have been made with only a minimum of brouhaha. In an online forum for reality TV post-production employees, one poster remarked recently that he was working on “a new show that actually started as a union show… The fact that it started under a union contract to me speaks volumes as to how the industry is starting to shift.” Indeed, in the first half of 2013, more than 20 newly union unscripted programs — shows running the gamut from American Ninja Warrior to American Baking Challenge — entered into IATSE contracts early on in their seasons, sometimes even before the starts of principal photography, without anyone having to heft a picket sign.

In addition to the many individual productions that have signed contracts, two powerhouse reality production companies, Reveille and Endemol, have joined Fremantle in negotiating agreements covering all their future shows. Those term agreements, too, were negotiated without any interruption of work or other disruptive disputation. More and more, employers in this sector of the industry are coming to the table of their own accord, before being pushed there by their employees.

In the jargon of union organizing, such growth is sometimes referred to as “top-down organizing.” There is no single agreed-upon definition of what constitutes “top-down organizing,” but it is a term generally used to refer to any organizing strategies that fall outside the category of grassroots, or “bottom-up,” organizing. Grassroots organizing focuses upon the mobilization of rank-and-file employees to wrest bargaining power from their bosses. If grassroots organizing is all about employees standing up together to demand more, top-down organizing is about persuading employers to step up to the table to offer more.

Seemingly effortless advances in top-down organizing in unscripted television, or any other largely non-union sector of our industry, will continue to be made if and only if employers know that crews are prepared to flex their muscles and forcefully unionize non-union workplaces.

Agreements covering work in scripted television and features are generally achieved through some manner of top-down action, with management recognizing the wisdom of offering employees union terms of employment on the front-end of a project, before employees have begun to clamor for a contract. Producers of scripted fare have come to understand that signing an IATSE agreement is simply a routine part of getting a project underway. Now, more producers of unscripted fare are starting to think similarly.

Top-down organizing is usually invisible to individual employees, because such deals are reached amicably in conference rooms rather than contentiously in the streets. Union negotiators work all the details of the deal out behind the scenes, as a routine matter of business. No employee is asked to wear a button, don a union T-shirt, sign a petition, or step away from his or her job. Absent any such action, the contract can seem to appear out of nowhere, as if by magic.

But top-down deals do not simply appear by magic. Nor is the apparent dichotomy between top-down organizing and bottom-up organizing really straightforward or absolute. In fact, all union contracts — whether they be obtained top-down through discussions with management in the early stages of a project, or bottom-up through pressure that restive employees bring to bear upon their bosses — ultimately derive from the same source: the solidarity of the workforce.

When employers come to the table and agree to provide union benefits and terms of employment, without their first being forced to do so, it isn’t magnanimity that inspires them to sign contracts. Nor is it some kind of magic wand that the IATSE waves; the union possesses no sort of special power by which we can mesmerize management and make non-union employers bend to our will. The only thing that motivates employers to sign a top-down deal is their recognition of the wisdom of reaching an amicable agreement on the front-end of a project, which is preferable to them to dealing with the disruption and duress of bottom-up organizing from the crew. In short, our top-down victories happen only because employers prefer to pre-empt their bottom-up defeats.

More and more, employers in this sector of the industry are coming to the table of their own accord, before being pushed there by their employees.

Seemingly effortless advances in top-down organizing in unscripted television, or any other largely non-union sector of our industry, will continue to be made if and only if employers know that crews are prepared to flex their muscles and forcefully unionize non-union workplaces. If folks want the union to conjure up contracts covering non-union employers, as if by magic, then they need to be ready to make the magic happen. That means that members need to call in their non-union work and need to be willing to stand together with their colleagues.

Whether contracts are forged quietly behind the scenes or banged out with a ruckus in the street, know that it is our members’ commitment to one another — the magic of solidarity — that makes contracts happen.