by A.J. Catoline

There’s a lot of strike talk in the air. Workers are frustrated. They’re not getting a fair deal to advance up to the next level. They are looking for a spark of magic to shake things up. They need to find their voice. A union! Brothers and sisters unite! Stand up now! It’s a timeless, existential labor crisis of “Whose side are you on?”

We could be talking about the Motion Picture Editors Guild, whose members are super-charged and woke in a campaign to improve their working conditions in the current union contract negotiation debate.

But in this article we are talking about the recent film Sorry to Bother You, the cult hit of the summer that’s a fresh and wild ride, visually ingenious and about so many things. The film from Annapurna Pictures is about a campaign to organize workers in a union, while exploring hip-hop culture, the obstacles to black success in America, how capitalism crushes the soul, and how corporations have a dark secret to hide. And all that happens in a film that is also daringly funny.

“I have great appreciation for the Editors Guild. We would be taken complete advantage of if we weren’t unified, and that is one of the many messages of the movie: Unchecked power is an extremely dangerous thing.” – Terel Gibson

Before creator Boots Riley made his directorial debut, he was a musician with a political hip-hop group, The Coup. Before that, he was a union organizer helping California farm workers and had volunteered for the Progressive Labor Party.

Riley says it took him a decade to get his film made with a well-crafted pitch:

“It’s an absurdist dark comedy with magical realism and science fiction, inspired by the world of telemarketing. Cassius Green is a black telemarketer with self-esteem issues and existential angst who discovers a magical way to make his voice sound like it’s overdubbed by a white actor. This catapults him up the ladder of telemarketing success — to the upper echelon of telemarketers who sell weapons of mass destruction and slave labor via cold calling. In order to do this, he has to betray his friends who are organizing a telemarketers’ union.”

When Riley finally got the funding to begin production, he set out on an ambitious schedule, even by independent film standards, shooting 60 locations in 28 days around his hometown of Oakland, California.

When you are a first-time director trying to assemble so many elements of your vision, it is not surprising that post-production is not considered until late in the game. The production was already a week into shooting before Riley had a conversation with the film’s editor Terel Gibson. CineMontage recently sat down with Gibson to ask how the movie was able to compile so many themes, visuals and story lines into a tightly paced, 105-minute runtime.

CineMontage: Boots Riley said that it was many years of challenge trying to get this film made. How did he find you on his journey?

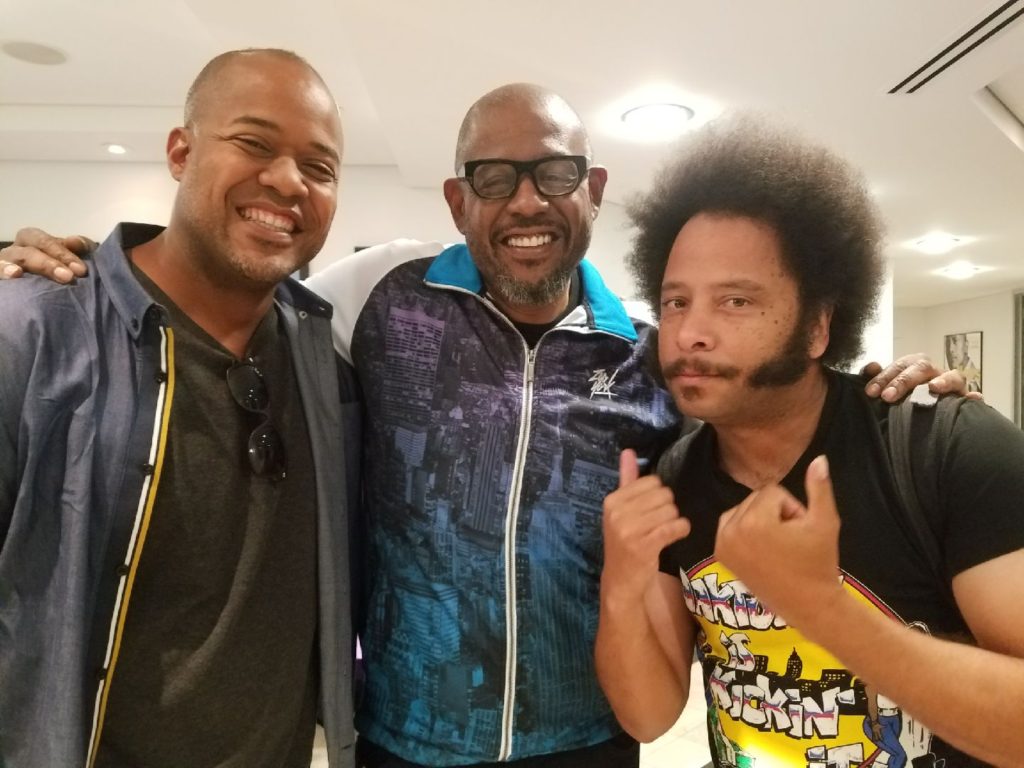

Terel Gibson: We have a mutual friend, with whom I had worked on a pilot — the director Catherine Hardwicke (Thirteen, 2003; Twilight, 2008). She was at the Sundance labs with him. When Boots was looking for editors, she recommended me. I loved the cast and the amazing script. We connected when they were about a week into shooting.

CM: A week into shooting?

TG: It was a very compressed schedule but that compressed it even more. I got on the phone with Boots the next day when he was on set between setups. We immediately connected creatively and I could tell what he was going for. He asked if I wanted to do it, and I said, “Absolutely!”

CM: They were shooting last summer and wanted a cut ready for the Sundance Film Festival submission deadline in September?

TG: We locked picture for Sundance in 13 weeks. That’s including a five-week shoot. Looking at the footage, I was like, “How is it possible they shot this in one day?” It was incredible what they were able to pull off during production.

Originally, the plan was to do post in Oakland, where Boots lives and where they were shooting. But ultimately it proved more cost effective for him to come down to LA. He would work with me Tuesday through Friday, and then go back to Oakland on weekends to work on the music.

I remember early on the producers asking if I thought we’d make the schedule. I was like, “Sure, absolutely!” But then I thought, “This is going to be a very tall order; it’s an incredibly complicated movie.” But when you have these strong performances and a director who has a clear sense of what he’s going for, anything is possible. It was hard work, obviously. With lots of nights and weekends, but even from the first pass, Boots’ unique vision really came across.

CM: What was it like working with a first-time director in the cutting room?

TG: Boots was very open to experimentation. But he would also be quick to say, “Leave it alone”’ if something didn’t quite work. There were a couple of sequences that we took out that were fantastic, but we didn’t want to slow the pacing and overstay our welcome. We had to be very critical of the moments that served themselves more than overall story. The goal was to give the film a sense of seamlessness and an unpredictable energy.

CM: When Sorry to Bother You premiered at Sundance, a review called it “the most bonkers film” at the festival. How did you weave together so many storylines and genres — comedy, hip-hop, social commentary and science fiction?

TG: I actually don’t think it’s all that bonkers. We tried to stay consistent going from moments of comedy to intense drama to the more horrific moments. It’s an absurdist dark comedy but I think we are also living in an absurdist dark comedy. Because every day we pick up our phones and live in this constant fear of what new absurdity today’s news cycle has in store. There is a great line in the movie where Steven Yeun [who plays the union organizer Squeeze] talks about how when people feel powerless to do anything about a problem, they just accept the problem. We can become so overwhelmed that we just get used to it. I think that is what makes the movie so timely.

CM: A movie about workers rising up in their union is indeed timely.

TG: I have great appreciation for the Editors Guild. I’ve been a member for 20 years now and thankfully we are organizing the membership. We would be taken complete advantage of if we weren’t unified, and that is one of the many messages of the movie: Unchecked power is an extremely dangerous thing.

CM: What else inspires you about the story?

TG: I’m super-proud to be connected to a film that illustrates inclusivity. It’s nice to see the message is resonating with audiences.

CM: Was it a challenge to cut the picket line scenes with so much happening on screen?

TG: We wanted the crowd scenes to feel like you were the eye of the storm. There’s a lot of handheld coverage and sound design to help fill out the world and make it feel like total chaos.

CM: Early in the film you use interesting transitions when Cassius Green (Lakeith Stanfield) starts on the job as a telemarketer, and he is thrust into strangers’ homes as he pitches them on the phone. How were those cut?

TG: In the scenes where Cassius drops down into people’s living rooms, it’s the first time I think the audience understands that this is going to be a very different kind of film. My approach was to try to make all of the drop-downs feel rhythmically unique.

One of my favorite transitions — which was a discovery in the cutting room — is when Cassius goes to the doctor and asks, “Is it bigger?” Then we cut to a great shot between his legs and his girlfriend Detroit answers that question in the next scene. There was initially a scripted scene between those two moments but losing it felt very intentional.

CM: What was it like cutting dialogue that was over-dubbed with characters putting on their “white voices?” Did you have those voices early in the cut?

TG: On set, they would have someone read the lines off-camera as the actors were mouthing the words. In the walk-and-talk scene in the office with Cassius and Mr. ____ [played by Omari Hardwick], the actors said all that dialogue and we dubbed the voices in later. We didn’t record the “white voices” until we were about two-thirds through the director’s cut. It was a very surreal experience when we brought those voices in because we had sort of gotten used to the original performances. Which worked in some strange other way.

With Patton Oswald’s voice, we recorded at a recording studio in Hollywood and then ran back to the cutting room in Santa Monica to see how it was feeling, and make adjustments. The next day, we recorded David Cross and threw that in. Rosario Dawson did the elevator voice, and Lilly James did the voice for Detroit during her art performance. She was shooting Mamma Mia 2 at the time, so she recorded via an Internet session. Basically, we were cutting the voices in as we went and our incredibly talented sound team refined it even more before the mix. It was such a bold choice and very important get feedback early on in screenings.

One of the main things we discovered was the importance of sync. The original intention was that it should be clear if it was overdubbed, but you don’t want it so wildly out of sync that it feels like a Kung Fu movie. We wanted it to feel odd but still rooted in the world Boots had created.

CM: Tell us about the assistance you had from your editorial department.

TG: My assistant editor Katherine Prescott did an amazing job. Her work ethic is one the main reasons we made it to the finish line. Kate helped so much with the visual effects, which there are a lot of in this movie, and thanks to her hard work we were able to include composite effects and replace green screen very early in the process.

We also had the luxury of working with composer Merrill Garbus from very early on in the process. She was able to send in all the score so I could modify the cuts to match the music perfectly. So when they did get to the dub stage, it was all there. As picture editors, we have to wear many hats these days, including cutting the music.

CM: How did you get started in the business?

TG: I started in 1997 on a film called Beloved working for Carol Littleton and Andy Keir as a post-production assistant. I could not believe I was working with the editor who cut E.T. I was like, “This is insane!” I got bumped up to an apprentice editor toward the end of that show.

Carol recommended me to Lisa Churgin for a film she was cutting called The Cider House Rules[1999]. That was my second job as an apprentice. So I came up the old-school way: apprentice, second assistant, first assistant, additional editor. I then started cutting on my own in 2010, as an additional editor with Pam Martin, a great friend and mentor, on David O. Russell’s The Fighter.

CM: Does the Editors Guild need to fight to keep the apprentice editor position as an opportunity for those starting out?

TG: I could not agree more. I think it is really important. That position hardly exists anymore. We need to train the next group so they are not dumped into something they are unprepared for. Working as an apprentice for a number of years, I got to learn process thoroughly before I even touched an Avid.

CM: Tell us a memorable story from your journey to becoming an editor.

TG: When I was on my first job for Beloved, they were shooting in Philadelphia and post was in New York. I was going back and forth on the train, from the cutting room with the sync film dailies, so they could screen those on set. And at the end of the day I would come back from set with the exposed negative and DAT sound to take to the lab.

Amtrak is a commuter train that goes express from New York to Philadelphia to Washington, DC. No stops in between. And it’s packed. And the train stops on the platform for maybe a minute. So I’m doing my daily run, I have a hand truck loaded with film boxes that I have to get off this train. I get one load off and onto the platform. There’s rush of passengers trying to get on. I’m fighting my way through getting the second batch of film off the train. As I get towards the door, I hear, “Stand clear of the closing doors! Next stop Washington, DC!” And the doors close! I see the film still out on the platform! The train starts to move… “Oh shit…” I had run this scenario in my head before, and I knew what I would do. And the only option you have in that particular moment is to pull the emergency brake. It works really well. It stops the train immediately on a dime.

The doors open. The conductor comes out and yells, “What happened? What are you doing?!” I explained the situation. He looks at me, a 22-year old kid on his first job, and tells me that I had just committed a federal offense. I said, “I am incredibly sorry, but if I didn’t get off this train my career would be over!” He saw the film boxes and said, “Don’t do it again. Have a good day.” I packed up the dailies and never told anyone that story until years later.

CM: So as an apprentice editor, you saved the picture? And the exposed negative?

TG: One hundred percent! Now we send dailies digitally, so nobody will have to relive that again.

CM: What advice do you have for those starting out as editors?

TG: You reboot your career at every stage of this business, in terms of compensation or the scale of the projects you are working on. But that’s what it takes to work your way up the ladder. For me, there was no magical thing that happened. It was just a long, long time of hard work. But it can pay off.

And save your money, so you don’t have to make choices for the wrong reason. You just got to hang in there. And when an opportunity arises, seize it!