THE EDITORS BEHIND APPLE+’S NEW SERIES HAVE A PERSONAL TIE TO THE MATERIAL

By Rob Feld

“I remember the first time I discovered bacon as vividly as the first time someone yelled racial slurs while pushing me around on the walk home from school,” Nena Erb said. Erb was one of four picture editors on the first season of Apple TV+’s “Little America,” an anthology series about immigrant life in the United States. It’s one of the best-reviewed series of the year since its January premiere, with a 94% “fresh” rating on the review aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes.

For Erb – who emigrated from Taiwan at an early age – making the show cut close to home. Those early experiences “shaped who I am today [and] definitely informed my choices when I was cutting ‘Little America,’” Erb says.

Inspired by a magazine series, the show’s half-hour episodes each function as a standalone tale taken from one of America’s millions of immigrant stories. Along with Erb, the Season 1 editors were Geraud Brisson, Hilda Rasula, and Janet Weinberg.

For those on the team with direct or close ties to immigrant experiences, the series also presented an opportunity to draw from personal feelings and knowledge, and to bring attention to experiences often given short shrift in the media.

Rasula grew up in Los Angeles with a Finnish father and Chinese grandparents who ran a laundry near Paramount Pictures. “For me, undoubtedly one of the coolest aspects of this show is that we’re telling stories about people that are rarely front and center on American television,” she said. “The immigrant experience is something that was not my own childhood story, but was part of family lore and really informed my world view — a certain sort of built-in otherness, which I think is a common second-generation feeling that also involves a culture clash of the old guard and the new. Eating homemade lo-mein, washed down with Coca-Cola.”

When Rasula was in middle school, her family moved to a small college town in Canada, and she lived in France for her last year of high school.

“Ironically, it was these two non-American experiences that I prob-ably drew on most in cutting ‘Little America,’” she said. “Feelings of disorientation, of homesickness, of loneliness in a new country are all experiences I know well, and I think they’re an interesting part of the story that ‘Little America’ explores.”

“I remember the first time I discovered bacon as vividly as the first time someone yelled racial slurs while pushing me around on the walk home from school, to the day we became American citizens,” she says. “That, and all the experiences in between, shaped who I am today. My experiences definitely informed my choices when I was cutting ‘Little America,’ especially for “The Son.”” Erb’s episode, “The Son,” chronicles the journey of Rafiq, a young man who travels from Qatar to Damascus, where he and his friend, Zain, were met with gay slurs on the street. Rafiq’s brothers also assaulted Zain for hiding him, leading Rafiq to flee to Jordan, where he waited for asylum to immigrate to America.

“While my own experience wasn’t that dramatic,” Erb said, “I could relate to the hurt he felt with each slur, the loneliness that washes over you as you’re trying to build a new life in a country where you know no one, the anticipation for immigration papers, and the wonder mixed with confusion when you first set foot on American soil. In a million years I never would have guessed that I could tap into my own immigrant experience for my work.”

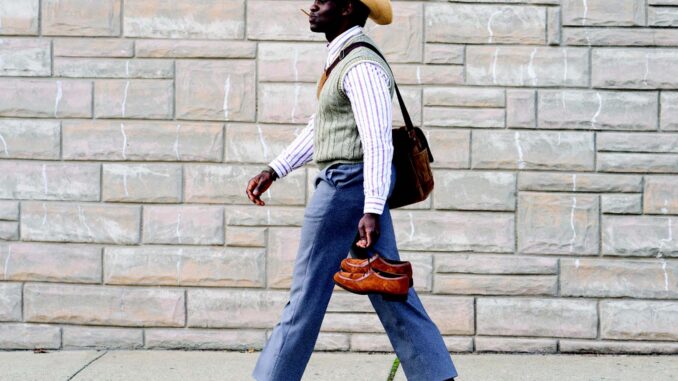

“Little America” features a broad range of stories: A Nigerian graduate student in economics struggles to adjust to university life in Oklahoma (“The Cowboy”); to build a home, an Iranian family struggles to move a massive rock from an otherwise perfect piece of real estate in Yonkers (“The Rock”); the only daughter to be sent to America from a Ugandan family of 22 siblings finds a piece of the American dream by selling chocolate chip cookies from a basket she carries on her head (“The Baker”); the rarified world of competitive squash is navigated by an undocumented teenager from Mexico (“The Jaguar”).

The stories are intimate and strive to bring their audiences into the specifics of the culture and personalities they are exploring, each concluding with a photograph and postscript about the real-life character on which they were based.

“This was one of the biggest, most democratic, and collaborative producing teams I’ve worked with in a long time,” said Erb, who also cut the episode “The Silence.”

“It was also important to our show-runner, Lee Eisenberg, to have the process be similar to that of feature films, where the director is involved until the end. There were many voices involved in the process; however, I felt my opinion was always heard. They assigned producers to oversee each episode while making sure everyone’s notes were taken into consideration. We would bounce ideas, discuss concerns, and experiment. For me, the ability to take big swings without fear of failure was liberating.”

Rasula, who cut episodes “The Cowboy,” “The Rock,” and “The Grand Prize Expo Winners,” describes a process that saw Eisenberg covering the East Coast locations and showrunner Siân Heder in Los Angeles working in the writers’ room and with the editors in post-production.

“We really needed both of them in each place just to try to handle the thousands of decisions made each day to get the story to the screen,” Rasula said. “There weren’t any particular instructions given during production, so much as a lack of instructions. It was really like, ‘We’re trusting you to know your job because we are slammed, so we need you to take the footage and run with it!’”

Rasula described creative debates with producers revolving around trying to be as generous as they could be with characters while trying to be specific and sharp in the storytelling. “We didn’t want one character to seem like they were representative of their whole native country or ethnic group, and yet the anthology format of the show could inadvertently lend itself to that interpretation,” she said. “That was an ongoing concern.”

“I’m an immigrant — or I became an immigrant,” said Brisson, a native of France, who cut “The Baker” and “The Jaguar” episodes. “That feels more accurate. In that sense, I think I would identify to the feeling of being an outsider and yet feel at home. I thought a lot about my attachment to the United States, why I had come here, and how important it had become for me to live in a place where you could meet and get close to people with such different backgrounds.

“During my job interview, Lee, Siân, and I discussed the challenge of telling a story based on actual people, and about how important it was that each story felt personal,” recalled Brisson. “We also talked about tone and the line between drama and comedy. We didn’t have any set rules like you might have on some series, where they would have been established in the pilot episode. We approached an episode like its own short film. My directors, Aurora Guerrero and Chioke Nassor, both had strong, personal, and different points of view for their respective episodes. “The Jaguar” was about squash and was conceived like a sports movie, for instance. But after Aurora and I played with having the name of our character on screen at the beginning of “The Jaguar,” we ended up using that idea for the other episodes.”

Because each episode includes a different culture, language, and sometimes country, each editor relied heavily on the expertise of his or her collaborators. For “The Manager,” about a 12-year old boy, Kabir, who must learn to run his family’s Utah motel after his parents are deported back to India,Weinberg referenced the work of the episode’s director, Deepa Mehta, and cultural expertise of executive producer Kumail Nanjiani and star Suraj Sharma.

“In addition to informing much of the episode with her cultural perspective,” Weinberg said, “Deepa designed some fun, traditional Bollywood transitions that jump the characters forward in time. For example, 11-year-old Kabir lowers his head to the sink to wash off tears, and when he raises his head, he is 17-year-old Kabir, now the grown manager of the motel. Kumail noted a scene that he felt was so untypical of an Indian family, that ultimately it was lifted, and Suraj brought his own improvised, Bollywood dancing to a hallucinogenic party scene.”

“Because ‘Little America’ is an anthology,” said Brisson, “the sense of the whole maybe wasn’t as significant as making sure you would feel a personal connection to each story, and our directors were essential in that regard. As an editor, I felt I had to focus on depicting our characters with honesty and to be mindful of the tone. And if we managed not to get in the way of the emotion, not to feel manipulative, then we’d be in a good place from one episode to the next, regardless of how different the stories were.”

Cultural accuracy and voice aside, an unexpected challenge for some of the editors proved to be cutting dialogue in a language that they do not speak.

For “The Son,” Erb worked with two different translators who spoke Arabic and a cultural advisor who made sure the songs chosen didn’t have lyrics that could offend. For “The Silence,” about a French woman who falls in love at a silent retreat, she relied on colleagues Brisson, who comes from France, and Rasula, who is also fluent in French. The episode, written and directed by Heder, is an interesting case in that it has very little dialogue, but when its protagonist, Sylviane, finally speaks at the end, she pours out her soul in an extended monologue in French to the man at the retreat for whom she has developed feelings without ever sharing a word. It was a departure for the series and a particular challenge for Erb who, with numerous characters and storylines to follow, was greatly concerned with maintaining clarity and keeping an audience engaged.

“Reading a script for a silent episode and watching a silent episode are two very different things,” she explained. “When you’re reading, you know the intention of the writer because it’s there in print. But everything is left to the viewer’s interpretation when there is no dialog to help frame the story. Would the viewers pick up upon what I was trying to convey without that framework? So, Geraud’s and Hilda’s help was critical when it came to cutting down parts of Melanie Laurent’s monologue at the end. It was important to make sure we were losing what wasn’t necessary without losing the heart of what she was saying.

“The other challenge to this episode was that Siân didn’t want to rely on music to help carry the emotion so there was nothing to hide behind,” she continued. “It was all up to the choices made in editorial to get the story, the emotion, and the comedic moments across.”

Editing can be a particularly political position on any show because it sits at a nexus among multiple creative contributors with controlling stakes. While, as in most television shows, the editors had limited time with their directors, all of the producers of Season 1 had varying degrees of involvement with the writing and shooting of different episodes.

“Each episode would have notes from all the producers, of course, but then we would also get editing time with specific producers,” said Rasula. “The trick of that was balancing out the varying interests, opinions, and tastes of each producer. The fun of it, though, was get-ting to work with so many fantastically talented people. Obviously, each immigrant is the star of their own life story, and it was refreshing to edit scenes that explore what that experience feels like — from huge, momentous life events, down to the most odd, granular little instances, which were the moments that delighted me the most.

“This is a show that is less interested in the politics of immigration than it is in the emotional experience of it,” Rasula said, “and I think that was a smart approach.”