HOW THE EDITOR PUT TOGETHER THE YEAR’S BIG ACTION SEQUEL

By Peter Tonguette

Picture editor Richard Pearson, ACE, did not set out to become a comedy specialist, an action guru, or a comic book connoisseur—but somehow, he has evolved into all three.

In his attempt to craft a diverse, unpredictable career in post-production, Pearson has pivoted from one genre to another. Early in his career, he edited a series of broad, and broadly appealing, comedies, including Frank Oz’s “Bowfinger” (1999) and the first sequel in the “Men in Black” trilogy (2002). After trying his hand at action with the James Bond film “Quantum of Solace” (2008), the editor then became embedded in not one but two comic book universes: After cutting Marvel’s “Iron Man 2” (2010), Pearson moved onto the DC Extended Universe. He was one of multiple editors on “Justice League” (2017) and is now the sole editor on one of the year’s most anticipated new releases, “Wonder Woman 1984.”

“I was always very keen to make sure that I didn’t get pigeonholed: ‘Oh, he’s the comedy guy, or he’s the action guy or he’s the drama guy,’” Pearson said from London in March, when he was putting the finishing touches on “Wonder Woman 1984.” The film was first set to drop in June, but the Covid-19 pandemic prompted Warner Bros. to shift the release date several times before finally settling on Christmas Day for streaming on HBO Max.

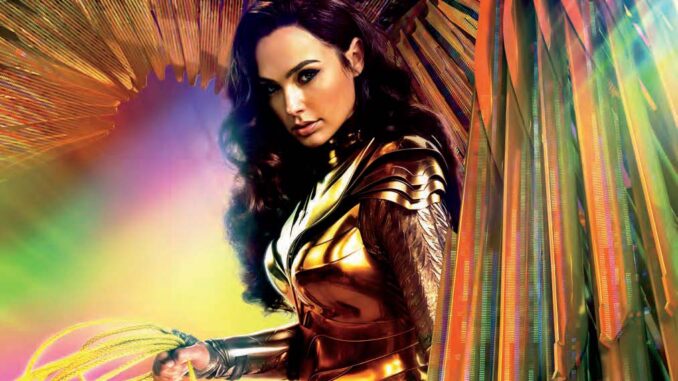

The sequel to the 2017 blockbuster “Wonder Woman,” “Wonder Woman 1984” represents a reunion for many of its key players: Director Patty Jenkins is again calling “action” and “cut,” while Gal Gadot resumes the role that won her legions of fans in the earlier film. In the sequel, Gadot’s Wonder Woman (and/or her alias, Diana Prince) finds herself entangled with pilot Steve Trevor (Chris Pine) and ensnared with the villain Cheetah (Kristen Wiig). This time, instead of the earlier film’s World War I setting, the setting is America in the year that Ronald Reagan won re-election—or, if you prefer, the year foretold in a certain novel by George Orwell. Jenkins co-wrote the screenplay with Geoff Johns and David Callaham, from a story she co-wrote with Johns.

get pigeonholed.” PHOTO:CHRISTOPHER FRAGAPANE

The new kid on the block is Pearson, who stepped in after the editor of the first film, Martin Walsh, ACE, had already committed to another project.

For her part, Jenkins said that the depth and breadth of Pearson’s experience made him an ideal fit for “Wonder Woman 1984.” “What is so important on these movies is that you have somebody that has this incredibly broad skillset—where they’re not only an incredible technical editor but they also have incredible humor and drama and emotions,” Jenkins said, and Pearson fit the bill. “I did like his body of work, and I liked that it both had ‘Bowfinger’—screen comedy—and it had action.”

A native of Minneapolis, Minnesota, Pearson did not grow up with dreams of bringing to life a legendary, lasso-wielding comic book heroine. In fact, his ambitions were considerably more modest. “When I was a kid, I was fascinated by television and film,” Pearson said. “I realized when I was in high school and college, wow, if someday maybe I would be able to work at WCCO-TV in Minneapolis. That would be the pinnacle.” As it turned out, near the end of his education, Pearson won an internship at the station that turned into a job. “That’s when I realized I actually had other aspirations,” he said.

Those aspirations first took Pearson overseas, where he spent several semesters at what was then known as the London International Film School, and then to Los Angeles, where he started hustling for work. “At that point, I realized that I’d had enough practical experience in very basic film/television production techniques,” Pearson said. “I arrived in 1988, in the middle of a writer’s strike, so there was absolutely nothing going on. I was cold-calling little independent features that were going into production.”

The editor’s efforts paid off when he was hired to work on a low-budget science-fiction comedy, “Mutant on the Bounty” (1989). “They said they might need a PA, so I convinced them and then worked for free for two weeks,” Pearson said. “They were so happy with me they paid me $50 a week—that’s really true.” Additional credits followed, including commercials, music videos, and episodic series, before the editor had the opportunity to work on a career-changing project: HBO’s miniseries about early space travel, “From the Earth to the Moon” (1998). “I saw the ‘From the Earth to the Moon’ project as a possible bridge to the feature world because they were working with primarily feature directors,” Pearson said. Of course, in those days, television editors had a tough time making the transition to feature films. “I was always told at every level: ‘Oh, you’re never going to be able to go from television to features,’” he said.

Enter Frank Oz, to whom Pearson had been recommended by “From the Earth to the Moon” director Jon Turteltaub. Oz, the director of a string of successful commercial comedies, was looking for an editor to cut “Bowfinger.” “I said to Frank in that interview, ‘Look, there are dozens that can come in here with resumes ten times as long as mine, but they all came from somewhere. I just want to let you know that this is me coming from somewhere,’” Pearson said. “He was great, because he was so confident and really just needed someone that he could hang out with in the room but also was competent enough to operate the box.”

For a while, Pearson accumulated credits in comedies, but Oz gave him an early opportunity to flex his editorial muscles: In 2001, Pearson edited “The Score,” a tough-minded heist movie starring a much-ballyhooed cast of acting heavyweights—Robert De Niro, Edward Norton, and Marlon Brando. “It was a real advantage to me, trying to build this multifaceted career, that this was Frank’s next choice,” Pearson said. “I think that displayed to others that, ‘Oh, maybe he can do different types of things.’”

In a sense, Pearson’s eclectic resume prepared him for his eventual entrance into comic-book-derived pictures. For example, his experience working on the effects-heavy comedy “Men in Black II” helped make “Iron Man 2”—his first comic book feature—an easier experience. “I really like working in that sandbox where it’s very malleable,” Pearson said. “You can say, ‘Well, if it’s not this, it could also be this. You could fly from here to here,’ or whatever it is.”

When Patty Jenkins was searching for an editor for “Wonder Woman 1984,” she turned to her collaborator from the first “Wonder Woman,” Martin Walsh, as well as producer Charles Roven—both of whom had worked with Pearson on “Justice League” and sang his praises to the director. “I think that people don’t realize how incredibly important editing on these kinds of movies is,” Jenkins said. “It has to be meticulous, but it needed to happen from a completely emotional place.” Pearson was thrilled to get the nod. “She was kind enough to give me a try,” he said.

Then the work began. Although Pearson traveled with the company from location to location—including stops in Washington, DC, London, and the Canary Islands—the editor and director did not work all that closely during the long, grueling, 128-day shoot. “During production, I’m very singularly focused,” Jenkins said. “You have to work on post to a certain extent, but I’m like: ‘We’ll edit it when I get there. I have to just focus on shooting for now.’ Particularly because he and I didn’t know each other, I didn’t have a shorthand with him and I didn’t have time to put attention into investing in the future.” Pearson anointed himself what he called a “lighthouse captain”—if he saw something wrong, he’d let her know, but otherwise, he’d keep plowing through the material. “I said, ‘Unless I see something coming toward the rock, I’ll just keep going,’” he said.

Unbeknownst to Jenkins, though, Pearson was already in sync with his director. When Jenkins sat down to view the editor’s cut, she was astonished—not by the things she wanted changed or tweaked, but by how much she liked it. “It’s always the worst day of your life, watching the first cut of the film,” Jenkins said. “But I did not have that experience. It was working for me, and there were surprises and delights, beginning to end, and I cried through the end of the movie and had all these emotions on something I had nothing to do with the editing of.”

“It was a real sweat for me, because that could’ve been my last day on the job,” Pearson said. “Fortunately for me, she was very, very happy, and then we moved into the post process.” Jenkins found herself in agreement with most of the takes Pearson had selected, but even when she had a different idea, she recognized what he was trying to do with a scene. “When I would want to change something, my direction to him would be just like my direction to the actor,” Jenkins said. “Instead of saying, ‘I want Take 35B because that’s what I circled,’ I would say, ‘Oh, I see what you were going for. You were trying to be funny and it’s his point-of-view, but I thought it would be funnier if we were in her point-of-view and she was surprised by what happened.’ I’d walk away, boom, totally new scene would come back—perfectly done.”

In effects-dependent movies like “Wonder Woman 1984,” numerous scenes have already been previsualized. “I began incorporating live-action footage into the previsualization, sometimes using the VFX editor to help me composite live action into a previs plate,” said Pearson, but that didn’t stop him from experimenting—even with action or effects scenes. “I was struggling in one set piece where a young actor needed to move from point A to C. As prevised and shot, the B transition point wasn’t really working. I had the VFX editor, Tino Brodt, mock up a bit of digital set extension and an “actor” to help communicate to Patty and Dan Bradley, the second-unit director, what that beat could possibly be. It was a very helpful tool and ended up being the solution for that problem.”

Jenkins was appreciative of Pearson’s resourcefulness in manipulating digital material. “He will cut multiple versions where he is saying, ‘Well, in this one she stays in duress longer, and then she makes a move at this moment. Well, in this version, there’s a way we could do it where she makes the decision much earlier,’” Jenkins said. “He will take a single frame of just performance and split it multiple times where he’s created a shot that never happened.”

Yet, to paraphrase Shakespeare, the sound and fury of “Wonder Woman 1984” does signify something; unlike so many movies based on comic books, this one is rooted in character, the editor said. “There is so much heart and depth to this character, Diana Prince,” Pearson said. “That noble and pure quality is really upheld by Patty, and we were always trying to service those sides of her. Frankly, Gal Gadot is half-a-step away from actually being that person. She obviously doesn’t have superhero capabilities, but she is just a lovely, lovely woman—kindhearted and so giving. It’s really astonishing and refreshing to work with material like that.” The editor said that he often lingered on “moments of compassion” that flicker across Gadot’s face, choosing to stay on her until “the very last frame possible.”

For Pearson, working on the film was a blast from the past, especially when he dropped by a decommissioned mall in Washington, DC, that was turned into a 1980s-era shopping center for the film. “I’m 58 years old, so I was right in the middle of all that,” he said. “It was really freaking me out to walk around this mall and to see Chess King and RadioShack—but with the RadioShack logo from the ’80s. It was like a visual slingshot back to my younger self.” The editor even flashbacked to his roots at WCCO in Minneapolis—that dream job that wasn’t quite. “There was an opportunity to cut an infomercial, which wasn’t unlike an infomercial that I would’ve cut back in the ’80s when I was working at the television station in Minneapolis, utilizing some of the same kind of ridiculous graphics and transitions,” he said.

For her part, Jenkins will have a tough decision if she makes a hypothetical “Wonder Woman 3”—will it be Pearson, or Walsh, or both in the cutting room? “At the end of this movie, we were actually trying to juggle something for a minute, so we actually brought Martin in,” she said. “They’re both mind-blowingly talented editors—the best editors I can imagine.”