By Jennifer Walden

At the start of the COVID-19 lock-down, there was much talk about “flattening the curve,” as in reducing the number of new COVID cases. But another curve has been flattening as well: the learning curve for remote editing. The longer the pandemic stretches on, the more comfortable editors are becoming with working remotely. Issues like securely sharing assets, syncing drives, reviewing visual effects, or cutting on an AVID without being in a studio have all been worked out to some degree and, more importantly, are continuously being improved.

Visual effects editor Sharon Smith Holley, who is also Secretary for the Editors Guild’s board of directors, has a unique and thorough perspective on just how much editing has evolved. Back in 2007, she started an archive for MPEG that not only includes vintage editing tools, but also has a photo collection of editors at work. She said, “I have a photo of Carol Littleton, Bruce Cannon, and Kathleen Korth working on “E.T.” on a Moviola. I have a photo of Editor Randy Morgan working on “ER,” and he’s using this little chunky computer. We’ve gone from that to multiple screens to flat screens and you think, ‘What could possibly be next — holograms on the wall or something?’”

Holley is asking people to send her photos of their remote editing setups to document this new chapter in history. “Editing is happening differently now, which allowed us to keep working through the pandemic. I’ve heard people say they don’t ever want to go back to the cutting room because of what remote editing allows them to have in their personal life, like being around their kids,” said Holley, who is currently remote-working on a major feature film for Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) in San Francisco from her home in Los Angeles and spending time with her cat.

ILM has studios in several major cities around the world: Singapore, Sydney, London, Vancouver, and San Francisco. They already had a handle on remote collaboration before COVID hit and were able to quickly set up Holley for this current feature. “I’m using a lot of different software — some proprietary — and platforms to upload cuts and get material for the Avid, get media, do reviews, and so on. It’s all browser-based. I’m actually remoting into an Avid that’s in San Francisco,” said Holley. She’s using remote desktop software (similar to Chrome Remote Desktop, or AnyDesk) to connect her laptop to an Avid at ILM. All the assets (like new shots, dailies, plates, etc.) are accessed remotely via Avid NEXIS.

ILM has studios in several major cities around the world: Singapore, Sydney, London, Vancouver, and San Francisco. They already had a handle on remote collaboration before COVID hit and were able to quickly set up Holley for this current feature. “I’m using a lot of different software — some proprietary — and platforms to upload cuts and get material for the Avid, get media, do reviews, and so on. It’s all browser-based. I’m actually remoting into an Avid that’s in San Francisco,” said Holley. She’s using remote desktop software (similar to Chrome Remote Desktop, or AnyDesk) to connect her laptop to an Avid at ILM. All the assets (like new shots, dailies, plates, etc.) are accessed remotely via Avid NEXIS.

ILM also sent Holley a large monitor that acts as an extension of her laptop’s screen space. “I can drag something to the left and it goes over to the big monitor so that I’m able to look at a cut full-screen, or have more real estate for the Avid bins.”

ShotGrid (formerly Shotgun Software) is being used to share and organize information for each shot and asset that passes through the film’s post-production pipeline. It’s a project management database that “keeps track of all the handles, the frames that are in the cut, technical information like lenses that were used on set, notes from the director, editor, or visual effects supervisor — anything that the artist and the visual effects editors might need to know, like if there are clean plates or if there are references for lighting,” explained Holley.

“There are so many people working on a shot on the visual effects house side — between lighting, animation, and clean up — and they all need to know and have access to a system that tells them if the cut’s changed, what’s changed about it, what are the notes, and when was it last reviewed. There are all of those pieces and elements for one shot, and ShotGrid is able to link them all together,” she added.

Once a visual element or edit is ready for review, it’s cut into the sequence to see how it plays with the surrounding shots. There are several ways that remote reviewing sessions can happen between the visual effects editor, picture editor, and director. One approach is to use software like cineSync (from Cospective) for high resolution, high frame rate video playback. Review session attendees log in with a session key. A sequence is loaded up, and it can be played forwards, backwards, and paused; attendees can draw on the screen. “You can look at a scene and draw a circle and say, ‘I want more horses over here,’ or ‘have the dove fly through the screen in this pattern or this pathway.’ cineSync has been around for a while and it’s a reliable way for people to review sessions,” noted Holley. “Also, the review sessions are recorded so others can watch them later and hear people talking about what needs to be done on a shot. That can be more effective than just reading written notes.”

Sometimes, less sophisticated review methods work, too, especially when dealing with poor internet connections. Holley recalled working on a project where pointing her laptop’s camera at the large screen monitor in her cutting room allowed the review session to continue. Holley affirmed, “It’s a brave new world out there; you can pretty much be anywhere and see what’s going on with your visual effects reviews. At times, you may need to go to a facility for a review session on a big screen — for instance, if you’re judging color and it has to be accurate. Other times, it doesn’t need to be as high quality.”

Oscar-nominated film editor Tom Eagles (known for his Eddie Award-winning cut of director Taika Waititi’s “Jojo Rabbit”) recently remote-edited the upcoming Netflix film “The Harder They Fall” for director Jeymes Samuel.

As Samuel was shooting the film in Santa Fe, Eagles was editing at home in New Zealand and his first assistant editor John Sosnovsky and second assistant editor Sam Bellamy were working at Pivotal Post in Los Angeles.

Every morning, Sosnovsky would spend a few hours matching their project content on the Avid NEXIS with Eagles’s local drive in New Zealand. Using the remote access software LogMeIn, Sosnovsky could open Eagles’s local drive, copy that media to the NEXIS, and then copy any new assets over to Eagles’s drive. “I spent a lot more time managing media than I normally would. I would use folders to track whether or not something was sent to each system. Every folder had to be assigned a location of where it was from, a date that it was made, and then a drive that it was going to,” he explained.

Thanks to the time zone difference between L.A. and New Zealand, Sosnovsky could make sure that Eagles started each morning with the new dailies from Santa Fe and prepped scenes from Avid in L.A.

Eagles said, “I’d cut on the Avid all day and even go into the night. I’d send notes to John via email. It was an odd interaction but it worked out because I could cut on my own all day without any distractions. I was screening cuts with Jeymes each week via Evercast.”

“The Harder They Fall” is a dramatic western that features complex, stylistic gun battles, so another editing assistant, Jason Barnoski, was added to the team to cut in sound effects. “Jason was working from home using Jump Desktop to connect to an Avid at Pivotal that was also on the NEXIS. So that was another folder that I had to manage and send to Tom, who was still editing on his local drive in New Zealand.”

After production wrapped, the project moved into post-production at De Lane Lea in London. Sosnovsky said, “We had to copy over the NEXIS, and ship it over to London, where we brought on two new people: Daniel El-Hendi (assistant editor) and Steve Mates (visual effects editor).”

But London was in lockdown when Sosnovsky arrived, and no one could get into the studio. Eagles remained in New Zealand working on his local drive, while El-Hendi, Mates, and Sosnovsky worked on local RAIDS that were synced to the NEXIS at De Lane Lea using a backup and file synchronization program called GoodSync. “We synced our local systems each night; I was still managing Tom’s system, too. Tom’s system became the master system. His project was the master project. I would grab the reels from him every morning and bring them into a folder on the NEXIS. We were still using the folder-naming convention I set up back in LA. Then everybody grabbed the reels they needed for that day — mostly for sound work and visual effects — and worked with those on their local RAIDS because the internet connection wasn’t great,” explained Sosnovsky. This process of nightly syncing happened for nearly a month.

Then Eagles headed to London at the end of January. “I couldn’t delay anymore. I had to go to London. Fortunately, the assemble was in a really solid place, but Jeymes and I just needed to get into a room together,” he said. At De Lane Lea, it was back to a typical in-house Avid workflow but Sosnovsky kept their local RAIDS at home up to date in case anyone fell ill. This way, they could continue working remotely.

Samuel, who was both director and composer on “The Harder They Fall,” did most of his composing at home rather than in a studio due to COVID restrictions. Eagles said, “Jeymes was demoing songs but he wasn’t exactly scoring to picture. There’s a bank robbery scene and everything is synced to the music. That sort of happened in post. The early demo was just the beat that was made up of gunshots. With just a bit of tweaking to the picture, I could get most of the gunshots in the beat to sync up with what was happening on-screen.”

Managing media assets — what’s coming from where and from whom, and who needs what to be up to date — was essential to keeping “The Harder They Fall” from falling apart. Sosnovsky decided that having one person handle all the media was the best solution under the circumstances. He said, “I could design a better system with drop folders for a future project, but we were jumping into it without having experienced remote editing before, so we designed our approach on the fly. Fortunately, I had two strict rules: don’t throw anything away, and don’t overwrite any folders. Archiving everything saved us a few times.”

Editor Autumn Dea – who edited director Cooper Raiff’s 2020 SXSW Grand Jury Award-winning narrative feature “Sh*thouse” — is currently remote editing an upcoming documentary film for director Doug Pray. She’s also dealing with a huge amount of media but using a different approach. When Dea joined the film last August, there was already 350 hours of footage captured. And now, a whole year later, there’s even more. She said, “The on-boarding process and setting up for editing remotely took a beat, but we’re working with Cricket Lane (an off-line editorial and finishing company) in Santa Monica, which offers a lot of tech support. Using TeamViewer (remote desktop software), their tech person was able to connect to my computer and set up my system.”

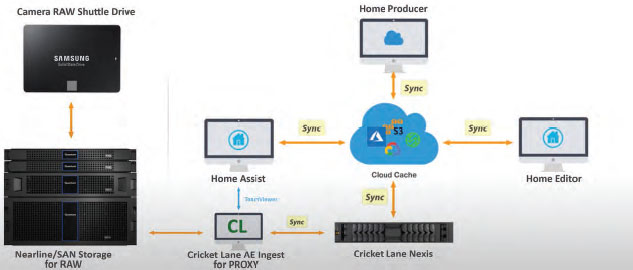

Dea explained Cricket Lane’s “sandbox” approach to remote editing as using StorageDNA’s data management services platform, DNAfabric, to connect her, the assistant editor, and the director (who are all working remotely) via shared S3 cloud storage. RAW production footage is copied from a hard drive to Cricket Lane’s nearline storage. The assistant editor adds this data to the project’s Avid NEXIS, which is synced to the S3 cloud. Dea and director Pray also have individual Avid systems on their computers connected to the NEXIS via the S3 cloud. The assistant editor can access Dea’s and Pray’s drives remotely to organize their project files from the root level. Dea said, “We each have our own Avid project on our own drives, but the sandbox allows us to share bins with each other. We drop bins and sequences from our individual project file into the sandbox and it’ll show up in everyone else’s project file.”

Assets are automatically synced using proprietary software that can be licensed through StorageDNA. According to Cricket Lane, it’s similar to sync services like Goodsync and Chronosync but has some Avid-specific workflows and clever solutions for bi-directional sync. Dea explained, “If I add something to my project, it will also be copied in the background to everyone’s drives. And their assets are copied to mine.”

When Dea is ready for the director to review a sequence, she drops it into the sandbox and he plays it back on his Avid. “Then we usually talk about it on the phone or via Zoom,” Dea said.

Dea concluded, “It’s been a pretty effective workflow, all things considered. Having the sandbox is definitely a step up from emailing bins, but it doesn’t compare to being able to work in the same project file, like you can do in the traditional Avid work-flow. It’s been a great solution for working remotely, though.”

Jennifer Walden covers post-production technology for CineMontage and other publications.