By Peter Tonguette

Neal Page and Del Griffith are on the road again.

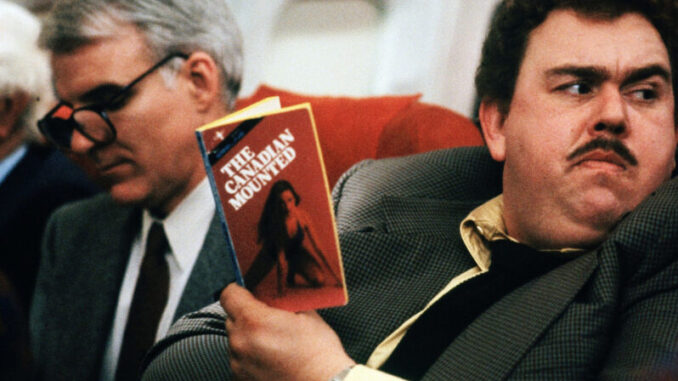

The famous cinematic odd couple — amusingly finicky businessman Neal (Steve Martin) and lovably oafish traveler Del (John Candy) — first traversed America’s roads and airways some 35 years ago, when writer-director John Hughes’s “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” hit theaters.

As every fan of the film will remember, Neal encounters Del during a long, interminable trip from New York to his hometown of Chicago, where his family is eagerly expecting his presence for the Thanksgiving holiday. Various snags and delays conspire to keep the unlikely pair joined at the hip for longer than expected.

Yet Neal and Del’s journey was once far longer than what was seen in the 93-minute theatrical release. Picture editor Paul Hirsch, ACE, assembled a first cut than ran 3 hours and 45 minutes — the longest, Hirsch said, of any first cut in his storied career, which also includes Brian De Palma’s “Blow Out” (1981), Hughes’s “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” (1986), Taylor Hackford’s “Ray” (2004), among countless other films.

Earlier this month, Paramount released a new 4K Blu-ray of “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” which includes about an hour and fifteen minutes of deleted and extended scenes pulled from earlier cuts of the film. Much of the footage consists of elongated versions of scenes familiar to audiences, including longer iterations of dialogue exchanges between Neal and Del. These scenes underscore, at greater length, both the tensions between Neal and Del as well as the closeness that develops between them; subplots are fleshed out — including a revelation that the motel-room thief who walks away with Neal’s cash was, in fact, a pizza boy who delivered a pie to the duo earlier — and one is glimpsed for the first time: As originally conceived, it turns out that Neal’s wife Susan (Laila Robins) suspected that her husband was unfaithful while on the road.

Any way you cut it, the deleted footage is fascinating — and even more fascinating are the memories of Hirsch, who recently spoke with CineMontage about the unique postproduction process on “Planes, Trains and Automobiles.”

CineMontage: How did John Hughes shoot “Planes, Trains and Automobiles”? In your book, “A Long Time Ago, in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away,” you write that the amount of film shot each day increased to accommodate rewrites by Hughes.

Paul Hirsch: He was less that way on “Ferris.” Perhaps the success of that film went to his head, I don’t know. But we were regularly receiving hours of dailies, more than I had ever seen before.

CineMontage: When you arrived at your 3-hour-and-45-minute cut, was the structure pretty much there? Was it just a matter of simplifying the storyline and shortening individual scenes?

Hirsch: It was there in the sense that scenes were not moved around, as we did on “Ferris.” There was no back story, and there were no flashbacks, except for the montage we concocted for Neal reflecting on the journey at the end. Too few pictures these days are written without a back story or a flashback. It’s a device that has become overused.

CineMontage: How long were you on the picture? I know you had to beat a threatened DGA strike on June 30, 1987, had your first cut done just after the 4th of July, and met the opening date in early November.

Hirsch: I overlapped with “The Secret of My Success” [1987] for about three weeks, so I started out behind. I was watching dailies in LA until I was free to join the company in Chicago. That was the last week in March of 1987. So eight months in total, I guess.

CineMontage: Now, about the recently unearthed deleted scenes! The Blu-ray states they came from VHS tape in the Hughes archives. Were you aware that this material had survived? Any idea whether other footage exists anywhere? (Maybe Paramount is only showing us the “best” or most interesting deleted scenes.)

Hirsch: I did know that John had a VHS copy of each cut, so obviously he had the long first cut, which included everything. The picture runs 1:33, so if you add 1:15 to that, you’re still an hour short of 3:45. There were a number of scenes that, as funny as they were at the time, with the changing times and mores would be considered in poor taste today. I think those would be among the ones left out. I would.

CineMontage: In the deleted material, there is much more dialogue in the plane between Neal and Del. What was the thinking behind shortening this, beyond the simple fact that it just goes on too long? Do we get enough of a sense of Del from a few choice jokes? For example, in the deleted material, Del shows Neal a pinup calendar advertising his shower curtain rings and makes fun of Neal’s first name.

Hirsch: The obvious answer is yes, the bit went on too long. The art, of course, is determining at what length it is no longer “too long.” There is a tricky balance to be struck between effectively demonstrating this guy is a bore, and boring the audience while doing so.

CineMontage: In the deleted material, there is a long version of the scene of Neal and Del being driven by a cab driver to their motel. This version is far more complex (even nightmarish) when played at length. The cab driver goes from being a benign oddball in the final cut to genuinely threatening in the long version.

Hirsch: I write about this in my book, “A Long Time Ago, in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away.” The scene as written was about a quarter of a page. When the dailies came in, it was clear that there had been a lot of material added to it. There were about four hours for this one ¼-page scene. I went to the head of postproduction at Paramount and got him to OK hiring another editor, Andrew London. I assigned him the scene so I could go on with the rest of the movie. I think it took him a week, during which hours of fresh material was coming in each day. I eventually promoted two of my assistant editors to cut alongside us, Peck Prior and Adam Bernardi. We all had our hands full. When we were cutting the picture down we returned the scene to how John had written it originally. And it wasn’t just a matter of shooting a lot that made it difficult. John would never cut the camera. When the actor finished a take, John would ask him for another, and then another, until the camera ran out of film. You’d hear the camera assistant yell, “Runout! Reload!” Meanwhile, we were facing an unknown number of takes in a 1000-foot roll, without slates to guide us to where they ended and a new one began. Try comparing line readings in those circumstances. And all this was happening with an extremely tight schedule and a deadline bearing down on us.

CineMontage: In the deleted scenes, the entire motel room scene is more complex, with Del sauntering into the bathroom as Neal is showering and the pizza guy (who later steals from Neal’s wallet) dropping the pizza. Why was this shortened?

Hirsch: The first motel scene was simply too long. We had to figure out how to cut it to the bone, while preserving the humor and drama and the story points. I’m happy with the result.

CineMontage: There’s much more of Del clearing his sinuses in bed. Are we hearing John Candy’s own voice here?

Hirsch: Yes, that was all Candy.

CineMontage: One deleted scene shows Neal’s wife and her mother speculating about whether Neal is having an affair while on the road. This is a big wrinkle in the plot — why was it dropped?

Hirsch: Yes, there were many phone calls home that we omitted, and we dropped that whole storyline, that she thought Del was made up, that he was just a phony excuse for Neal not coming home. The tone of the scenes was wrong for the overall film, and we were looking for things to cut. Maybe if we had more time, we might have figured out a way to make that work. Oh, well. I’m told that carpet weavers in the Middle East leave imperfections in their work, as a reflection of their own imperfection as human beings. I agree with that. I believe that the perfect is the enemy of the good.

CineMontage: We should talk about your most inspired editorial intervention in the whole film: Originally, the next-to-last scene unfolded chronologically, with Neal, having already said so long to Del at a commuter train station, learning of Del’s homelessness by happening upon him at another train station. You had the idea to intercut flashbacks with shots of Steve Martin looking puzzled on the train. This suggests that Neal is registering, in his own mind, that Del is homeless. You reworked the rest of the scene to make it look like Neal backtracks to find Del at the original train station. How did you arrive at this? Do you think Hughes had a notion that he might revamp the ending by shooting so many shots of Steve Martin on the train?

Hirsch: I can’t say what was in John’s mind when he shot Neal on the commuter train. When we watched the dailies, of which there were two hours, he never said anything to me about how he intended to use this wordless material. As for the benefit of cutting the scene this way, it is clearly better to have Neal suss out that Del is homeless. In the original, Del virtually throws himself at Neal’s feet and blurts out how miserable and lonely he is. Having Neal figure it out and have him go back to fetch Del makes Neal more empathetic and generous, and preserves Del’s dignity.

CineMontage: Do you have any opinion about the deleted material finding its way to the public on this Blu-ray?

Hirsch: It hadn’t occurred to me, frankly, that my work was being audited, but I’m happy for fans to be able to laugh at the stuff we all laughed at in the cutting room. I think that, as they watch it, they will understand why the shorter version is superior. Or maybe they won’t. No matter. I’m pleased that the picture, which lost the opening weekend to a picture no one remembers terribly much today, has become this iconic holiday ritual for so many fans.