By Peter Tonguette

Chaos, commotion, contention, and a whole lot of comedy converged on the night of October 11, 1975.

That night, NBC broadcast a sketch comedy program that boasted a cast of boundary-pushing, little-known eccentrics, multiple musical acts, one famous but unhappy host, the controversial presence of the Muppets, and language, subject matter, and innuendo that tiptoed over the line of what was decent (or, at least, what the network was willing to air). Oh, and it was all scheduled to air live.

The mayhem may not have been visible to those who tuned into the premiere episode of NBC’s “Saturday Night” (SNL’s original title), but it is at the center of one of the most distinctive releases of last fall’s movie season.

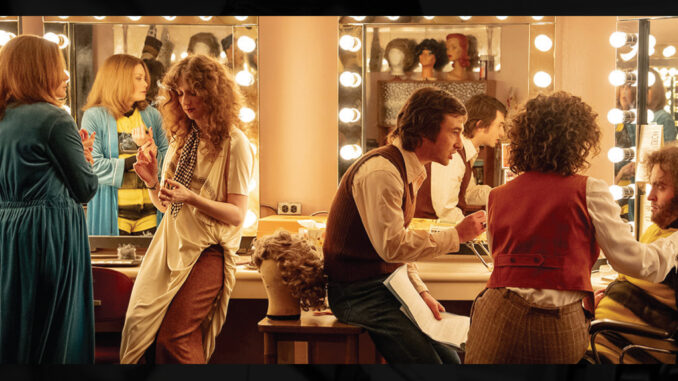

Director Jason Reitman’s “Saturday Night” parachutes the viewer into the innards of NBC’s Studio 8H on the momentous occasion of the airing of the first episode of the comedy series, which is presently in the midst of its 50th season. Back then, however, the show’s future classic status was far from assured. At every turn, Reitman, who co-wrote the screenplay with Gil Kenan, underscores the creative pandemonium that surrounded the effort to make the debut a success.

Unfolding in the hour-and-a-half or so before Chevy Chase exclaimed “Live from New York — it’s ‘Saturday Night’!” to those who had tuned in, the film pokes around the nooks and crannies of Studio 8H. (The studio was recreated on a soundstage in Atlanta.) Inhabiting this space are a gaggle of memorable characters: future “SNL” stars, including Chevy Chase (Cory Michael Smith), Dan Aykroyd (Dylan O’Brien), Gilda Radner (Ella Hunt), John Belushi (Matt Wood), and Garrett Morris (Lamorne Morris, no relation); producer Lorne Michaels (Gabriel LaBelle) and his wife, writer Rosie Shuster (Rachel Sennott); and NBC executive Dick Ebersol (Cooper Hoffman). Adding to the bedlam are Muppets creator Jim Henson (Nicholas Braun), performance-artist-style comic Andy Kaufman (Braun, again), and that unhappy first host, stand-up comic George Carlin (Matthew Rhys).

In time, the “SNL” cast would gain the moniker “Not Ready For Prime-Time Players,” but to bring the antic vision of “Saturday Night” to the screen, Reitman relied on a group of very ready-for-prime-time postproduction professionals.

CineMontage recently spoke with several of the most important players on the team, including picture editors Nathan Orloff and Shane Reid; supervising sound editor Lee Gilmore, MPSE; supervising sound editor and dialogue/ADR editor David Butler; dialogue editor Emma Present; music editor Chris Newlin; and re-recording mixers Will Files, MPSE and Tom Ozanich.

CineMontage: Nathan, you started on the film and were later joined by Shane. What was your approach going in?

Nathan Orloff: Jason is incredibly precise in what he shoots. He can be incredibly confident: “This is the way into a scene” or “This is going to be here.” He rarely shoots a widespread shotgun blast of “Get everything — figure it out in post!” That’s not Jason’s style. There are times when that shot he thought was going to be the opening shot was actually split in two, and then we cut back to it 30 seconds later, but there weren’t tons of alternate ideas left on the cutting room floor. We just wanted to keep what was singing and lose the stuff that wasn’t moving the story along.

CineMontage: Do you like to let scenes play out in long takes when they’ve been shot that way?

Orloff: I have this little voice I try to listen to when I’m watching something. If I’m enthralled and it’s working, I don’t have any desire to cut.

CineMontage: But it sounds like you had freedom to intercut scenes in a different order than might have been planned.

Orloff: Originally, the moment where Gilda is on the crane was separate from Jim Henson talking to Garrett Morris, and Dan Aykroyd talking about the gun under the bleachers. In the shooting, those were just singular little scenes, but when we intermingled all three, it told the story of: “This cast is out of control.” There’s a lot of creativity in the placement of scenes, even though there aren’t many different angles and coverage.

CineMontage: What was the workflow on the film like?

Orloff: I was in Atlanta from the beginning. Jason and I were very close on set. They shot Monday through Friday, and then Jason and I would spend Saturday together. I would show him everything I had done that week. One of the wonderful things about the movie existing on one night is everyone is in the same costume the entire shoot and lighting doesn’t change. I had a running note list of little pickups I’d love to grab, and it was easy to get these — close-ups of Lorne freaking out or something. It was a testament to Jason working closely with the edit.

Shane was still finishing “Deadpool & Wolverine,” so he started working on assembling scenes towards the end of the shoot. Once we got back to LA, he joined us in full force. That was an interesting and wonderful dynamic. I’m happy with how it worked out because Shane had a slightly outside perspective from coming in later.

CineMontage: Shane, did it feel like you were a fresh set of eyes?

Shane Reid: I think one of my strengths as an editor is that I came up doing a lot of short-form work. I could be an objective person and sort of re-look at material as a fresh voice: “Yes, you may have conceptualized it this way, and may have executed it this way, but there are also other ways of putting it together.” On “Saturday Night,” I was the first person to be able to step back and say, “Cool, but let’s check this out” or “Let’s do this with this here.” I think it helped Nathan unlock a little bit.

CineMontage: What were your impressions of what the movie needed?

Reid: We watched the assembly of the film with Jason just a few days after they had come back from shooting. We had it assembled and into shape enough at that point to watch it very early on. I had been scrambling to assemble scenes and keep up with the camera. Immediately, I thought the film was not frenetic enough. There were a lot of pacing issues out of the gate because some of these things that seemed like really well-orchestrated long shots did slow the rhythm down on film, even though they seemed chaotic at the moment.

CineMontage: The film should feel like we’re struggling to keep up with what’s going on.

Orloff: The idea was for the audience to join the film and say: “Wait a minute. This is going really fast. I think I’m following this. What’s that person’s name? Who is that again?” But hopefully, by the midpoint, you are totally into it and want everyone to succeed. That flow, that dynamic, was intended to sort of mirror what all the characters are going through in putting on the show. No one [involved with the show] had ever done anything like this before.

CineMontage: Yet amid all the chaos, we have Lorne’s cool, implacable disposition. Did you feel the movie was kind of anchored by his presence?

Orloff: Absolutely. He’s the thread that’s weaving through the tapestry here. Everyone is bouncing off of him. He doesn’t let anybody in emotionally except, briefly, Rosie. We needed to see private moments with him. Some of those were written into the script; some of them were stuff that we just pulled in during editorial and used music to enhance.

The thing I love about Jason’s approach is a little goes a long way. There were close-ups of the moment when we learn about the backstory of Lorne and Rosie’s marriage. But it was actually more intimate with the camera further away and you’re peering through the posts under the bleachers. It makes you lean in and want to hear what she’s saying. It’s more organic, and it’s definitely more Altmanesque.

CineMontage: Shane, you were responsible for crafting the few scenes that take us out of real time and allow us to vicariously experience Lorne’s internal panic.

Reid: Those are big swings. Those were mostly built by me being very anxious because I was having to double-up my time. I would be leaving Disney and starting at Sony at 8 p.m., and working until 3 in the morning. The film had come together really well. We always knew it would because the script was so fantastic, and the character arcs were kind of built into it. I had a lot to prove to continue to move the film forward with interesting ideas instead of just being someone else who was tidying things up or making some changes here or there, so I tried to look at the film in some very oblique ways.

CineMontage: There’s that moment when Lorne is observing bricks being laid on the set and, amid the brick-laying, has a kind of nightmarish panic attack.

Orloff: Shane had this wonderful idea: “OK, here’s a scene that works, but what if I cut a bunch of flashes to bricks and clocks and giant loud music and freaked everybody out?” It took me a second to get on board, and now I can’t imagine the movie without it. It’s essential.

Reid: That became a way inside a man who is difficult to get inside of. I said to myself, “This is like a giant jazz piece, and I think we can do things that feel different.” In some ways, the anxiety that I was feeling, trying to execute those at 2 in the morning, was similar to what Lorne was feeling in those moments, too. I would look at Lorne in the brick-laying scene and think, “I want to feel as uncomfortable with him as I feel in this moment right now where I’m taking a risk and I should be laughed at.”

CineMontage: Lee, can you talk about the sound design in the movie?

Lee Gilmore: Jason wanted things to sound authentic, lively, and energetic. One of the first things he told us was that of all the movies he’s done, this one was the most important in terms of sound, that sound was going to be such a huge player. So no pressure at all when we had our first spotting session! But he gave examples. He didn’t want to use any type of background beds. He didn’t want any kind of steady sounds that might make things murky. We were hyper-surgical in where we placed spotted backgrounds as we bobbed and weaved around the dialogue. As soon as you walk into the lobby, you are holding on for dear life, which I love. It has a very kind of old-school, almost Altmanesque feel at times with everybody talking over each other. I don’t know if I’ve ever worked on anything with that much energy popping off the screen.

CineMontage: As I understand it, instead of loop group, the loop group was extensively supplemented with principal actors, since all of the actors on set wore lavalier mics.

David Butler: In building the set, they actually copied the eighth and ninth floors of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, so there’s no edge of frame. Everyone could just be somewhere and could be acting. [Production sound mixer] Steve Morrow put a mic on everybody, and he also put Ambisonic Dolby mics in the ceiling. Steve was constantly recording the room. Jason told everyone, “Just act. Don’t pantomime. Actually act; actually talk.” That allowed us to make it really immersive where we’re not focusing on just what’s on-screen but we’re also picking up other conversations happening off-screen.

CineMontage: What was it like working with so many voices?

Butler: There are sections where you see every single person, practically the entire cast — John, Chevy, Gilda, Dick, the Teamsters — and they’re all mic’d, and we use everything. They’re having conversations. We didn’t want this to go to waste. Ella Hunt as Gilda has a distinctive voice. So does Dylan O’Brien as Dan. Let’s make sure we hear that once in a while. Maybe it’s not registering that it’s them, but we’re having their voices constantly in the background.

CineMontage: Emma, how was cutting dialogue on this movie different?

Emma Present: Often my first approach to cutting a scene is to grab the boom and then include the lav for some support of the boom. In this case, it was the other way around. There were so many people everywhere. I was impressed by what the boom op was able to capture, but in many circumstances, the lav had to be the hero and the boom was capturing the ambience of the room and got us some incredible reverb. But we were able to pan and treat everyone individually because they were all lav’d so well. We might be hearing Lorne Michaels have a side conversation while we’re focused on someone else center-view, but then we pan and hear that conversation continuing and it’s now center-focus. It couldn’t be loopers. These were the principal actors having all these side conversations. One of the main things Dave had me do was fill out those tracks with all of the side conversations so it felt like we were in it.

CineMontage: What tools did you use to clean up those tracks?

Present: If I needed to get someone else out of someone’s lav, I took [iZotope] RX and was very surgical about it. I have all my preprogrammed shortcuts, so I’m just typing on my keyboard. I go in and highlight frequencies and say, “I know this other person’s voice. I need to remove it.” Occasionally, a lav drops out or someone flubs a line. We were able to find alts, but these were such unique takes that you didn’t want to change out the way they were delivering the line.

CineMontage: Lee, how did you fill out the sound world of Studio 8H?

Gilmore: I combed through all these great 8H ambient recordings from Steve Morrow and found areas that had the most personality, whether it was a grip knocking something over or a rolling rack going by. Then it was about what spotted backgrounds, what flavors, felt right for when we’re in 8H, in the hallways, the affiliates’ room — that kind of thing.

CineMontage: Chris, talk about your work with the music. Jon Batiste, who appears on-screen as Billy Preston, crafted a score in live sessions in New York and then in Atlanta, where the music was recorded on the actual Studio 8H set upon the completion of filming on certain days.

Chris Newlin: After they wrapped, they gave Jon an hour or so to get out of his makeup into his street clothes. When the musicians returned, he had a few additional instruments: a couple of horn players and additional percussionists. They recorded in the space. They wanted it to feel live. The nature of what it was and how it was done gave it a different energy and feel. It ended up amounting to 40 to 50+ audio tracks.

Butler: What Jon did with the music — who would have thought this Brazilian and African percussion feel would work for a comedy movie set in New York City? And yet it completely works. It’s the motor that drives that entire mix in the movie.

Newlin: The New York sessions had some instrument isolation, but the percussion players were all in the same room. So there was some bleed. And obviously, on set you have the same problem: everybody was in this giant set and you have microphones picking up everything. It helped us in the mix to have control over the instruments that were closer to any given mic, but you still couldn’t just mute something. When they recorded on set in Atlanta, Jon would build out long stretches with Jason where it would be 16 bars of just shaker, or a shaker and bongos, allowing for layers and different dynamic structures we could then use in the edit.

CineMontage: How were those sessions built into the score?

Newlin: Between myself, Nathan, and Shane, we started cutting and rearranging the tracks to picture under Jason’s direction. The challenge was figuring out how to take this amazing music Jon created and shape it to picture without Jon having to come back and re-record it without the magic of being on set with the free improvisational feel of it all. It was important that it felt live and spontaneous and you didn’t necessarily know where it was going. It also had to drive the story and the picture. I started building these toolkits from the material Jon had created. Essentially, it would be anywhere from one to two bars to 16 bars of material that Jon did. I made it so the picture editors could also pull that into their Avid and use it as they sculpted scenes. That’s why our temp score was also mostly our final score. That, combined with a few overdub sessions with Jon that were mostly piano-focused, was how it all came together.

Butler: Chris was vital. I told him on a couple of occasions that it’s one of the top two music-editing jobs I’ve ever heard. “Elvis” was the other one. You can’t tell with Chris where the score ends and the needle drops begin. It’s seamless.

CineMontage: Will and Tom, can you talk about what you were trying to achieve in the mix?

Will Files: At any given moment, you have no less than a dozen people on screen overlapping each other — by far the most complicated dialogue recording on film that I’ve ever been a part of. On top of that, you have a score that was recorded on set. And then, on top of that, you have Jason’s strong desire to make this world feel as authentically like Studio 8H at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in 1975 and all the texture that comes with it.

Tom Ozanich: I went to an early screening before any temp mixes had happened. It was just the Avid temp mix type of thing. I loved the movie. I thought it had great timing and pacing. But it was hard to understand a lot of the dialogue. And that’s because a lot of stuff was piled on top of each other; people kept talking even when they went off-camera, or they started talking before they got to the camera. In the production mix track, that’s all married together.

CineMontage: What did you propose to Jason?

Ozanich: I said, “Would you be open to us starting to play around and pan some of the dialogue off?” I wanted to show him we could keep the “messiness” he wanted, but that’s more about the density of activity, not people talking over each other or our having difficulty understanding what they’re saying.

All these mics and tracks have different and opposing problems, and when they’re married together in a mix, you can’t do anything about it. But by keeping each mic and track separate from the others, I can adjust EQ to correct the problems individually. Then when we start to move them around and track the movement; we’re able to follow multiple events at the same time. Spatially, they pull apart and we can follow each event because, although they’re simultaneously audible, they’re not actually on top of each other.

CineMontage: Will, you went to some lengths to make the studio itself come to life through reverbs.

Files: I was thinking, what’s the sound of “SNL” from the TV-viewing audience’s point of view? What makes that show sound like that show? Everybody thinks of the music because there’s such a long history of great performances on that show, but the other part of it is that they’ve shot that show since 1975 in the same studio space, which has essentially remained unchanged. If you listen to any episode of “SNL” going all the way back to the first one, they all have the same reverberation character because they’ve never changed the room. Studio 8H was designed originally as a small concert hall for recording radio orchestras or broadcasting them live to the air. It was not built as a soundstage per se. It was built as an auditorium, and as such, it’s a pretty lively acoustic space.

CineMontage: What tools did you use to recreate that space sonically?

Files: We went to the original episodes and sampled the audio into a program called Accentize Chameleon. This plug-in uses machine learning to deconstruct the sound and create an acoustic sonic blueprint, then applies it to other sounds. It’s also able to export that as an impulse response file that we loaded into another new piece of software called FabFilter Pro-R 2, which is a multi-channel reverberation plug-in that we can use to build the Atmos. We were mixing the film in Dolby Atmos because we wanted the opportunity to take full advantage of all available audio channels. We were able to take this [stereo sample] from 1975, feed it into a very modern Dolby Atmos reverb plug-in in 2024, and create this beautiful, natural-sounding, multi-channel acoustic space that sounded remarkably like the actual TV show.

Gilmore: You’ve got to give it up to Tom and Will for doing such a great job of pointing your ears in the direction they needed to go. At times, the movie seems very much like a choose-your-own-adventure book. You have all these different stories going on: You can go over there because that story’s still going, but now we’re going to direct your ears over here to these characters. It was a masterclass in mixing. ■