by Laura Almo • portraits by Sarah Shatz (NY) and Martin Cohen (LA)

Click, crack, squish, smack, thud, boing, crunch, splat…

The old edict “Necessity is the mother of invention” certainly rings true for Foley artists — the people who create sounds for film and television. To be a Foley artist is to be creative and detail-oriented, intuitive and analytical; they must be in good physical condition and, as it turns out, quite often a mind reader.

The Foley artist must be able to perceive, feel and discern very subtle nuances of the human condition — whether it’s the way a person walks when she’s tired, moves when she’s asleep or slams a glass down at a party when she’s drunk. It may be the minutest details of a body shifting in a chair or the grotesque sounds of a person’s eye popping out of its socket.

From footsteps and body movements to playing sports, Foley artists re-create everyday sounds for a project, but they are not random. Everything audible the Foley artist fashions is always in service to the story. The hard-heeled, purposeful walk of an official is going to reflect the character’s dogged determination. The way a cup rattles when a professor puts it down suggests the nervousness she feels at her tenure meeting.

A STUDY IN HUMAN CHARACTER

“First and foremost, Foley is anything that a person in a film would do — footsteps, a prop they would pick up, or contact with other characters,” says New York-based Foley artist Rachel Chancey. “To friends and people who don’t know what Foley is, I often refer to it as the acting or character sounds; I always consider anything a person does to be something that I’m going to do in Foley.”

Chancey, who got her start at Spin Cycle Post in New York City and now works out of a custom-designed Foley stage in her home in Brooklyn, says she begins a project by watching the film to get a sense of the story. “I’m looking for what’s going

on with the characters; I’m watching and trying to get in touch with their emotional lives.” Having studied theatre at NYU, she sees a strong connection between acting and Foley, as they are both performance-based and studies in human character.

“Using my theatre background, I ask myself, ‘What are the characters feeling, what are they thinking, what is their intention?’ It all helps when I’m performing Foley,” says Chancey, whose credits include The Squid and the Whale, Midnight in Paris and HBO’s Treme, as well as the upcoming films Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: Sword of Destiny and Wolves.

REPLICATING SOUNDS

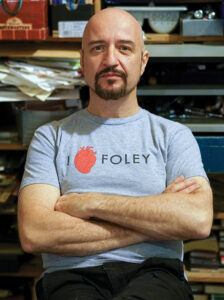

After watching the film or TV show and getting a sense of the character’s emotional world, Foley artist Marko Costanzo starts doing footsteps. A typical day will involve getting into costume, which for Costanzo is a pair of shorts and a T–shirt. He notes long pants are likely to create movement sounds on the tracks. “Footsteps might take up half the day,” says Costanzo, explaining that they would include anything from work boots to high heels on any number of surfaces, including marble, gravel and ice or frozen snow. “We look at whatever is on screen and try to duplicate that sound. From there, we’ll go ahead and do any of the body movements and all the actions that you’ll see actors do on screen — like opening doors, putting plates down and moving heavy containers.” His numerous credits include The Silence of the Lambs, The Departed, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, The Wolf of Wall Street and the recent Spotlight.

Hand-eye coordination is key for a Foley artist, according to Costanzo. And if this wasn’t exactly what got him in the door at Sound One in New York City, it is what got him noticed. Back in the day, he was a working magician with aspirations to be in show business. He got a job as a messenger at Sound One and, as part of his job, would go into every editing room to deliver 35mm trims. He would then show a magic trick. And then he would go into the next room and show another trick.

One thing led to another and eventually he got a job as an apprentice sound editor on Sophie’s Choice. As Costanzo tells it, one day he was given a chance to see the Foley room, where legendary Foley artist Elisha Birnbaum was working. When Birnbaum couldn’t find the prop he needed to make the sound of a pull chain light bulb, Costanzo offered to bring one in — and the rest is history. “That was my first Foley effect,” he says. “They actually let me do the pull chain and they used it. That was the start.” When Birnbaum announced that he was looking for a replacement, he took Costanzo under his tutelage and eventually Costanzo replaced Birnbaum and became a go-to Foley artist in New York City.

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE FEET

On the West Coast, where the craft of Foley was created (See sidebar, page 56), LA Foley artist Joe Sabella believes that “walking characters” is a window into their world. “If you really think about it, people’s feet depict what kind of personality they have,” he posits. And though there isn’t a way to generalize about the personality traits of Foley artists, the consensus is that being a good listener and paying attention to details are essential elements. As is being in good shape. “You have to coordinate your body, your mind and your ears,” explains Sabella, who began in features making sounds for such films such as The Little Mermaid, Back to the Future II and III and Hoffa. Nowadays, he works primarily in television. He worked on classic TV shows like CSI and The Sopranos, and is currently working on Scorpion, the TV drama loosely based on the life of computer expert Walter O’Brien.

For Sabella, one of the main differences between TV and film is the work schedule and the amount of time allowed to finesse sounds. “Since features afford more time to make the sounds more detailed, we tend to break everything down to its simplest form,” he offers. “Say it’s people getting in and out of a car; I would do a leather set sound to the seat and then maybe an impact of their bodies hitting the seat and then touching the steering wheel.” But in TV, he would combine sounds, following the same rules of detail, finesse and accuracy. Sabella maintains that the process and approach is the same; it is just the schedule that is accelerated. “I take the same mindset with features and apply that to my TV sounds.

CREATIVE YET TECHNICAL TEAMWORK

Therein lies the ingenuity of Foley artists. Both a technical and creative process, it requires them to use their heads and hearts — not just to duplicate sounds but to describe the world in which the characters dwell. “What we do is choice-driven,” explains Foley artist Robin Harlan, MPSE. “What prop we choose for each effect and what shoe we choose for each character makes a huge difference, not just in telling the story but in how it’s going to be mixed.”

The Foley team of Harlan and Sarah Monat, MPSE, have been making sounds big and small together for nearly 30 years in LA. Working at Sony Pictures, their credits include Titanic, the Star Trek reboot, The Interview and Hotel Transylvania 2, and they were recently working on Miracles from Heaven, due in March. Their partnership began in the mid-1980s when Harlan invited Monat to work on the night shift of a TV series called Traveling Man. “When Sarah and I started working together, we realized there was a really excellent synergy,” recalls Harlan. “My strengths and her strengths are different, but they work very well together.” Harlan likes big action and adventure films while Monat has a penchant for panache and timing.

“Working in partnership is huge,” adds Monat. This is especially important on Hollywood blockbusters where you’re moving big props. One person may be holding a prop while the other person is making sure it is correctly mic’d. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. In recent years, LA-based Foley artists have begun working by themselves, a work style that has always been the norm in New York, primarily for budgetary reasons.

For Harlan and Monat, however, working in partnership has enabled them to create some kind of work-life balance. They jokingly say they’ve been working together longer than most people have been married and in that time have seen fads and fashions come and go in terms of how supervising sound editors want their Foley. As Harlan puts it, there are some sound supervisors who want everything to be completely “vanilla” — very toned down with more of a suggestion of footsteps than the reality of feet. Others want bold and over the top.

WALKING THE WALK

The job itself requires impeccable timing and physical endurance, as well as a keen understanding of the human condition. “If you watch people’s feet, they depict what kind of personality the people have,” explains Sabella. A gangster walking with a sense of purpose requires a lot of weight, while a person who is emotionally drained is going to walk more sluggishly.

Choosing the shoes to make these textured and nuanced sounds is a whole art unto itself. From sneakers, heels, flip-flops and sandals to dressy men’s shoes and snow boots, a Foley artist’s shoe collection may have upwards of two hundred pairs. “You can dissect a shoe heel to toe and come up with a sense of which is heavier, lighter, bulkier, etc.,” says Chancey. There are some shoes that work really well and others that just don’t work; it depends less on the size of the shoe than the sound it makes. A 50-pound schoolgirl could be walked by a beefy Foley artist, while a 250-pound sumo wrestler may very well be performed by a petite woman. For example, when diminutive Chancey did the Foley for Christopher “Biggy” Wallace in Notorious, she used a bigger men’s shoe stuffed with socks and a microphone to pick up the low end.

Acquiring shoes is often a humorous endeavor, relates Monat. “People look at you strangely,” she says. “Employees want to help you with fashion, not sound.” Some of the best finds have been cheap shoes from second-hand stores, according to Harlan, who recounts buying expensive men’s shoes only to find they were unusable on the Foley stage. “Maybe you go to the Salvation Army and get a pair of shoes for 50 cents — and they’re the shoes you end up using for 30 years because they are fantastic and you’ll never be able to replace them.” Harlan reveals that she is walking Foley for the current series Madame Secretary in the same shoes in which she walked the character of Daisy in Driving Miss Daisy.

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

When it comes to props and shoes, every Foley artist has his or her favorite: a zippo lighter, a rusty hinge, a creaky table… They are collectors and accumulators.

“Calling me a collector is very kind,” Costanzo laughs. “I’ve been called a hoarder and a dumpster diver — affectionately, of course.” But this points to a larger truth about the art of Foley. In order to make sounds with fine shades of detail and nuance, you need all kinds of props, often in duplicate.

Just about anything is suitable as a prop, from antique phones, typewriters and radios to cornhusks and coconuts. Chancey, who works out of a 900-square-foot space on the cellar floor of her home, describes her prop collection as “part garage, part attic.” She adds, “I organize it by category: metals, plastics, things that roll, things that squeak, things that are squishy, toys, crinkly paper, crinkly plastic, natural stuff… I’ve got a whole area with seeds, pits, nuts, husks, coconuts and bones.”

Sabella acquired an expertise in bone-breaking sounds working on CSI for 15 years. When he wanted to get away from celery and other organics, which has long been the standard for bone breaks, he found alternatives that sounded just as authentic. “I use very thin wood for a bone break with a little sanding sound, and a lot of mud and grit for gush sounds.” Other tricks of the trade include corn starch substituting for snow. Or polenta to make it sound icier. And for ice cubes? Walnuts or “fake ice” made out of resin that won’t melt and change the way the ice sounds.

WHERE THE SOUND GOES DOWN

The Foley stage is where it all happens. So what does the Foley stage look like? At c5 in New York, Costanzo works in a 30-by-60-foot room with 18-foot ceilings. Built by re-recording mixer Skip Lievsay when he was still one of the owners of c5, it has foam walls, ceiling tiles and curtains. “We have a nice big reflective wall that allows you to cast or throw a sound 90 to 100 feet,” says Costanzo. The Foley stage also has mobile foam cushions that function as foam walls and can be moved anywhere to absorb the live sound, which is crucial when doing exteriors.

Harlan and Monat work on Sony’s original MGM Foley stage, a soundstage that could never be created now because of upgraded building standards. “This is the original MGM stage, built before the 1930s, so the dirt pit is grounded and not elevated on cinder blocks or cement casing. The pits and surfaces were built to last. This is Hollywood at its best,” Harlan explains. “It sounds more natural.” She says that the old-growth construction has a much different sound than what can be created with today’s structures. “Steel reinforcement and cinder blocks tend to create a cold sound,” she adds. “You just can’t get the warmth.”

Building regulations aside, much has changed in the way a Foley stage is designed, according to Sabella, who reveals that one of the real challenges is keeping outside noise from entering the Foley stage. “You’re always fighting ambient sounds, planes going overhead, trains passing by,” he says. At his Foley stage in Van Nuys, Sabella created a “room within a room” by doubling up the walls. This in effect sealed the Foley stage off from the outside world. “We had an acoustician come in,” he continues. “We designed our room with panels that are adjustable. We can change our ambience in the room at any given time to match any ambience that we see or hear in production.”

The digital age has undoubtedly changed the way in which Foley artists work, especially the way the sounds are recorded and mixed. But the art itself remains decidedly low-tech.

What has changed is the output. “We work a lot harder than we did 30 years ago,” Costanzo observes. “We’re able to accomplish a lot more in a much shorter amount of time, and that’s because of digital.”

The onetime magician sums up his job thusly: “I run in place quite a bit. I lift things up and I drop things. I pick things up, I put them down. I pick them up, I put them down. My job hasn’t changed in 33 years. I’m still banging two sticks together.”