by Laura Almo

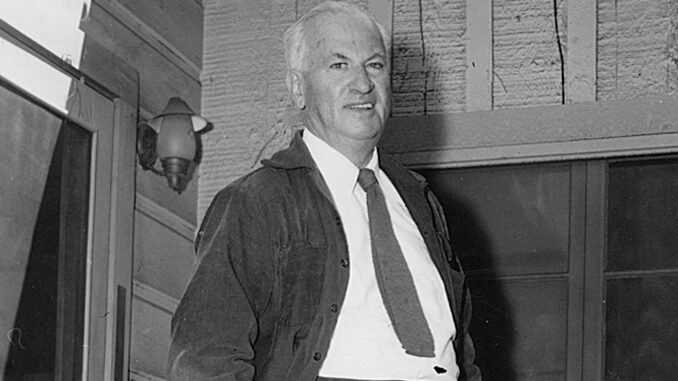

It was the late 1920s and Jack Foley was a producer, director and writer working at Universal Pictures at its old location on Ventura Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley. Just up the road on Barham Boulevard, competing studio Warner Bros. was busy filming The Jazz Singer. When The Jazz Singer, with snippets of sound, was a success in 1927, neighboring Universal soon realized it would have to jump on the sound bandwagon.

At that point, Universal was working on Showboat, a silent picture that would now become the studio’s first film to incorporate sound. Universal asked for studio volunteers to help with the process, and Foley, who was interested in sound and always up for a challenge, jumped at the opportunity. He worked with other volunteers to add rudimentary sound. For that first sound production, the studio rented a Fox/ Case-Sponable sound unit to record sound effects, music and voices for Showboat. This was recorded on Stage 10, one of the original sound stages at the studio, which now houses a dubbing stage and an ADR facility.

From there, things began to take off. Universal Pictures started doing more Westerns, and they called Foley in to do “footsteps” (this was the predecessor to the term “Walking Foley”). According to Catherine Clarke, Foley’s granddaughter and guardian of his legacy, Foley got so busy, he called in people from the prop department to work with him in what was referred to as “Foley’s area.”

This was the beginning of an art form — albeit one invisible and uncredited, as this job was called “sync to sound” (later termed “syncing”). All sound editors would do their own work. As movie sound evolved, so too did Foley. Migrating to the sound department at Universal, he continued to perform sounds for the studio’s films for 40 years, concentrating on footsteps and props.

Foley’s passion was infectious. A real people-person with a genuine love of life, he brought in anyone who was interested in making sounds for film, including family and friends. Before long, he had assembled his own group of people who worked together and developed their own tricks and techniques — one of which was to use a cane to create extra footsteps.

It was Foley who suggested that actor Walter Brennan put a rock in his shoe to create a limp for his role in To Have and Have Not (1944), and who rescued Spartacus (1960) from having to be reshot. When production didn’t get the desired sound of the chariot armor, Foley shook some old keys to re-create the sound and saved the picture. He worked his sonic magic on many other films, including Magnificent Obsession (1954), All That Heaven Allows (1955) and A Farewell to Arms (1957). Foley died in 1967 at the age of 76.

While these early practitioners created a staple of tricks and techniques, it was all kept under wraps. “Post-production [and sound effects] was one of the secrets of showbiz,” says Clarke. “Everything was supposed to be very real, and nobody was supposed to know what went on behind the scenes.” Indeed, in true Hollywood style, all the audience was supposed to notice were the stars on the screen and the story.

When Universal Pictures split up as part of the studio restructuring of the 1950s, Foley’s “disciples,” as they were called, went to work at different studios. “Some of them started working together in pairs,” says Clarke, “and because they liked Jack so much, when they finished a scene they would say, ‘That’s a wrap. Let’s Foley it.’ And that’s how it got started.” In the 1960s, Foley was officially recognized by Desilu, when the Hollywood studio named its sound stage “Foley’s Stage.” Adds Clarke, “The name took off but, aside from the guys who worked with Jack, nobody knew who or what ‘Foley’ was.”

The art remained in the shadows for many years. A function of history and tradition, Foley artists, as they came to be named, never received screen credit. Around the 1970s, sound editors were doing their own syncing (as it was called before becoming officially known as Foley), and realized they could hire outsiders to do this time- consuming and specialized work.

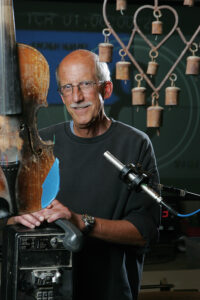

“There’s a certain kind of focus and a knack to doing this kind of work; you must be able to make nuances with your body. Many sound editors didn’t like doing the work or found they weren’t very good at it,” says David Lee Fein, MPSE, a longtime Foley artist whose career spans five decades, from the 1970s to the present, and includes MGM, Paramount and Warner Bros. “For a while, there was a bartering system where there might be a trade between sound editors — one who liked to do Foley and one who didn’t. Sound editors soon realized they could outsource this work.”

Some of the first people to be hired were dancers, as they had that combination of body control, rhythm and timing. One of the first professional Foley teams was Ross Taylor and Kitty Malone. Taylor was a sound editor while Malone was a dancer. Others were professional athletes.

By the 1980s, more people were becoming Foley artists but it wasn’t until the end of the decade that they began regularly receiving screen credit. The hidden art of Foley was now recognized — although by a specialized Hollywood term that few people outside of the entertainment industry knew.

This changed in the early 1990s, when there were a few pivotal stories that sparked public interest in the craft. In 1992, The Wall Street Journal. ran a front-page feature on longtime Foley artists Ken Dufva, MPSE, and Fein, and not long after, The Los Angeles Times began running short “behind the scenes” films that played in theatres before feature films.

“The LA Times did a short with Foley artists John Roesch and Hilda Hodges, and Foley mixer Mary Jo Lang,” says Alyson Dee Moore, a Foley artist and Editors Guild Board member, who had partnered with Roesch for many years. “That was a big breakout,” she says. “Once that short film came out, a lot more people were aware of what Foley was.” And a lot more became professional Foley artists.

It was by happenstance that Clarke ran into Fein and Dufva while visiting the Paramount

lot in the early ’90s. “We were chatting a bit and I said, ‘I’m Jack Foley’s granddaughter.’ And that shocked the daylights out of them.” Since then, Fein and Dufva have been instrumental in raising awareness about the craft of Foley and introducing a new generation of people to it. Also in that decade, the work of Foley artists was further recognized when the Emmys began giving statues to award winners instead of certificates.

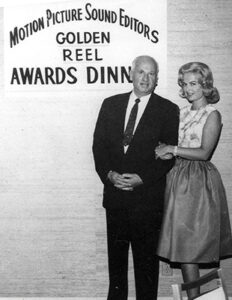

In 1997, Foley the man was honored posthumously with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Motion Picture Sound Editors, which also had made him an honorary member in 1962. Foley artists were admitted into the Editors Guild in 2006.

Few industry professionals can claim that their name is a noun, a verb and an adjective all at once — let alone a post-production craft and an Editors Guild membership classification.

Of the notoriety and recognition bestowed upon her grandfather, Clarke says, “I think he would have been embarrassed. He wasn’t really a showbiz person. But underneath, I think he would have been pleased.” Above all, Foley was doing work that he absolutely adored, she adds. “He put his heart and soul into it. He really loved it.”