by Betsy A. McLane

Images courtesy of A Century of Sound. All rights reserved

Have you seen Laurel and Hardy do exactly the same skit in both a silent and a sound version? Was it actually the quality of John Gilbert’s voice that doomed his career in the talkies? What beloved classic movie used Fantasound? Why did editors resist changing from optical to magnetic sound? Do you know the reason Alfred Newman’s opening musical fanfare for 20th Century-Fox suddenly got longer? And most importantly, can you explain why “push-pull” was perhaps the most important sound technology invented during Hollywood’s Golden Era?

All these answers and much more knowledge can be found in A Century of Sound, a two- volume, multi-DVD/Blu-ray collection that takes the viewer/listener on a journey through the history of motion picture sound, from its beginnings in the 19th century through 1975. A third volume, continuing the saga of cinema sound to the present, will follow in the near future. To say that this is a thorough and meticulous project is a vast understatement, and even if one thinks one knows film sound, there are revelations galore in store here, thanks to the formidably knowledgeable Robert Gitt, who wrote, produced and directed this vast undertaking.

Gitt, who retired after almost four decades of service as preservation officer at the UCLA Film & Television Archive, was partnered in this endeavor with Robert Heiber, recently retired president of Chace Audio (now part of Deluxe), a noted expert in sound restoration and preservation, who served as production supervisor and one of three executive producers on the project. Heiber began the Rick Chace Foundation to commemorate the work of the late Rick Chace, inventor of restoration equipment and founder of Chace Sound. The foundation, whose “mission is to ‘break the silence’ on the history, art and technology of motion picture sound through education, outreach and empowerment,” and the UCLA Archive worked together for 20 years, along with numerous other industry supporters, to create this definitive exploration/explanation of Hollywood motion picture sound.

A Century of Sound began as a live, 180-minute presentation by Gitt at the 1993 conference of the Association of Moving Image Archivists, the world’s largest organization for professionals in the field. It was received with wild enthusiasm that demanded follow-up and expansion. Over time, Gitt repeated and refined that presentation in many venues, projecting film clips with their original sounds (hiss, edit pops, flutter, etc.) included. The need to make these into a more permanent, accessible record was obvious.

The resultant project certainly meets that need. For instance, those who associate the start of movie sound with Vitaphone’s Jazz Singer (1927) or Lights of New York (1928) may be surprised. At least as early as 1902, Leon Gaumont in France introduced the Chronophone, a sound-on-disc system that synchronized with images on the Cinematographe. Also, in 1911, Eugene Lauste exhibited sound on film in the United States. A major purpose of the project is to give the unsung innovators of every era their due, and Gaumont and Lauste are only two of the many dozens of inventors, engineers, artists, scientists and businessmen who are cited. Some, like Gaumont, are well known; others, like Lauste, might be forgotten if not for efforts by Gitt and fellow historians. There are plenty of people to credit, since no advancement in sound becomes mainstream without input from multiple creative and competitive sources, from studio heads to sprocket manufacturers.

Speaking both on camera and as off-screen narrator, Gitt details the earliest attempts to reproduce sound onward through an exhaustive — and sometimes exhausting — step-by-step history. The first volume, 2007’s The Beginning, extends from 1876 only to 1932, the time when sound pictures eclipsed silents. The next volume, 2015’s The Sound of Movies (1933-1975), emphasizes optical sound, documents the transition to magnetic, and ends with a discussion of Dolby technology. Added to this detailed mix is the rapidity of sometimes concurrent developments, and the fact that while different technologies were employed simultaneously, some were in use for only a couple of years.

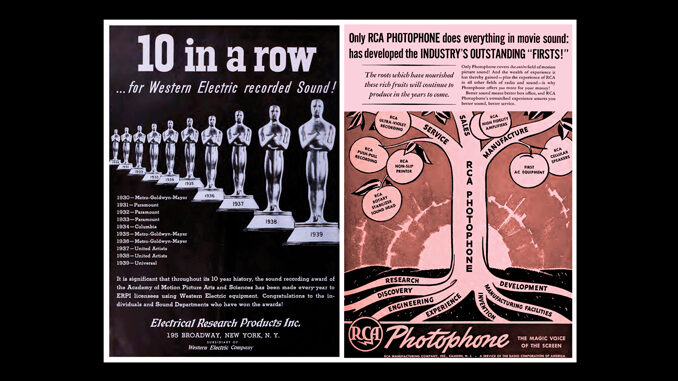

There are finely drawn patent diagrams of machines, portraits, myriad close-ups of ever- evolving devices, and comparisons of various film stocks, perf holes, aspect ratios and microphone enhancements/placements. Soundboards are on display as well as production stills from all phases of shooting, lab work, editing, exhibition and equipment maintenance. Richly colored posters tout the glories of particular sound systems to moviegoers. Period trade advertisements provide charming punctuation: Marilyn Monroe, in a slinky formal gown, gazes adoringly at a new CinemaScope lens, which helped capture her voluptuous widescreen glamour in How to Marry a Millionaire.

Summarizing the heated debates about the merits of various processes, Gitt also delivers intricate stories about the sometimes-startling business of Hollywood — like the remarkable tale of how William Fox was driven out of business. Producer Fox, in addition to being largely responsible for ending Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company stranglehold on America’s early movie business, was key in making sound films commercially viable. In 1925, a year before other studios showed a commercial interest in sound, Fox acquired 90 percent of western hemisphere rights to the German Tri-Ergon patents, which included important flywheel patents for talking pictures. He also bought rights to Theodore Case’s Movietone sound system in 1926.

Movietone sprang from the Phonofilm research of Case, Lee DeForest and Earl I. Sponable, and is a name now most associated with Fox Movietone newsreels. Fox also purchased the patents of Freeman Harrison Owens (who was previously sued by DeForest for patent infringement). The first Hollywood picture using sound on film technology was Fox Film Corporation’s 1927 Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans with a synchronized musical score and sound effects.

Those who actually made the films were less affected by competing sound systems and patent wars; they generally worked with whatever equipment the studio supplied. In a 1928 photograph of the 13-member Hollywood Vitaphone sound crew — which was creating sound sequences for Warner Bros. features and making 10-minute sound shorts documenting performances of singers, jazz bands, comedians, etc. — every man wears a tie, and only two are without suit or sport coats. The “Vitaphone Shorts” segued into dramatic shorts, one of which, Night Hawks (1928) grew to seven reels. Retitled Lights of New York, it became the first all-talking Vitaphone feature. The editor of Lights of New York, Jack Killifor, who continued working until his death in 1956, received credit on the main title card.

One of A Century of Sound’s treats is the visual and aural presentation of different variable density and variable area optical, and later, magnetic tracks. There were many types of tracks in the variable area optical category alone (unilateral, bilateral, dual bilateral, etc.), which are shown singly, side-by-side and on the sides of picture film clips. The merits and drawbacks of each, as well as the ways those drawbacks were minimized by further inventions — such as modifications to the Western Electric light valve — are explained.

For the makers of this project, there were challenges not only in restoration of the original films, but in finding a way for the viewer to see and hear actors while simultaneously looking at the soundtracks. “We printed the clips in a manner that departs from the normal way optical tracks are printed,” Gitt explained. “Normally, optical sound is printed 20 frames before the picture to compensate for the fact that picture goes through the projector gate intermittently, but sound is picked up continuously. An image of the sound projected on screen along with the picture would then be out of sync with the actors.”

Warner Bros.’ Rebel Without a Cause (1955) was a CinemaScope production released in both mono (optical) and four-track stereo (magnetic) formats. Selecting a quiet love scene between James Dean and Natalie Wood, Gitt isolates the four unique stereo tracks that exist on one piece of film and explains what each brings to the final mix of music, effects and dialogue. The fourth, and thinnest, track contains only a background of chirping crickets that comes into play toward the end of the scene. The sound in this film is not exceptional, but in his dissection, Gitt allows the audience to “see” the sounds in various configurations. It must have been a big job for Rebel sound editor Carl Mahakian (uncredited), but it continues to bother Gitt that while car radios in 1955 were all mono, the music coming from Dean’s car radio is an audio anachronism because it is stereophonic — de rigueur for the era.

The triadic relationships among business (money and law), invention (science and engineering) and artistry (filmmaking craft) is an underlying theme of Century of Sound, although this is implied through examples, not stated directly. For nearly 50 years, the two major companies, Western Electric and RCA, licensed their original track negative recording and playback systems on a non-exclusive basis. In general, studios elected to license one or the other. In a few cases, a producer might license both. Each company housed extensive research and development departments, sales teams and maintenance technicians. Each also had different, often highly demanding specifications for lab processing, as well as theatrical projection and loudspeaker systems. It was customary to “brand” a film with its sound system, including the corporate logo, as “RCA Sound Recording” or “Western Electric Recording.” As might be expected in the early days of sound, patent wars and suits were common, including an especially bitter battle between the German cartel Tobis-Klangfilm, which controlled the European rights to sound-on-film technology, and Western Electric and RCA, which aligned against Klangfilm.

The multitude of sound types challenged directors, editors, recordists, mixers, cinematographers, laboratories, theatre owners and projectionists. Executives made final decisions about which format and equipment to use, generally in consultation with heads of post-production, but always based on the economics of running their studios. Especially powerful was Douglas Shearer, head of MGM’s sound department, who, with John Hilliard in 1938, developed theatre speakers; their “Shearer Horn System” became a standard for many years. Western Electric incorporated it into its Mirrophonic Sound System to provide better sound quality in theatres that could afford to re-equip. Thousands of exhibitors had older equipment still performing well and settled instead for less-expensive “equalization,” in which an engineer sat in a theatre auditorium with a set of variable tone controls. When he was satisfied that the best results had been obtained from a sample reel, the frequency correction was measured and built into the theatre’s amplifier system.

Shearer, winner of multiple Academy Awards, began MGM’s sound department in 1927 and was the director of its technical research until his retirement in 1968. The three main executives at 20th Century-Fox concerned with sound were Earl I. Sponable, Edmund H. Hansen (both in the 1930s), and Carl W. Faulkner (who became head of the sound department by the 1950s); Loren Grignon was also very involved in sound and stereo sound research for the studio.

Over the years, each studio had its own mix of formats, and editors who had to make sense of the miles of sound footage. They initially balked at the shift from optical to magnetic because they were accustomed to “reading” visible sound marks on optical tracks. Some complained about having to use a “squawk box” to review the audio and mark the cuts with grease pencils because it slowed them down. For a short while, editors continued to be able to demand an optical “work track,” even when the film was recorded magnetically.

By 1950, Paramount Pictures’ head of sound Loren Ryder had converted the studio entirely to sprocketed 17.5mm magnetic audio, rendering optical sound obsolete for production — although not for exhibition. The full history of magnetic sound from wire recording through Stefan Kudelski’s (who along with Col. Richard H. Ranger came up with NBC’s three-tone radio chime) development of the NAGRA recorder and onward is thoroughly examined.

A Century of Sound acknowledges the importance of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in developing standards and giving awards in the sound field. In 1938, AMPAS set up a committee to study theatre sound equipment by testing sample soundtracks from each of the Hollywood studios in various movie theatres to see how well — or how poorly — they sounded compared to the same soundtracks when heard during the final mix at the studios. Based upon measurements they made, the committee came up with a standard equalization setting by which technicians could adjust theatre amplifiers to produce sound that would work well with the most recent Shearer Horn two-way loudspeakers. In this way, audio heard by audiences would accurately reflect the original audio quality heard by the sound mixers. Sound in theatres therefore would avoid treble frequencies that were too muffled or shrill, or bass frequencies that were too weak or tubby and boomy. Named Academy Curve, this standard lasted almost 50 years.

A prime example of Gitt’s meticulous care taken to make clear the dozens of technical topics in Century of Sound is the explanation of push-pull, an optical recording technique used to decrease distortion as well as to increase audio fidelity while reducing noise, before the widespread adoption of magnetic recording. Its rather sweet sonic quality is illustrated by a surviving original music track from Gone with the Wind (1939), quite unlike the restored versions of the film that have screened for decades using soundtracks altered to meet later audiences’ demand.

The Fantasound roadshow version of Fantasia (1940) is the only known example of push-pull use in exhibition, with sound from a separate dubber interlocked with the projector, requiring Disney technicians to be present in the theatre to make adjustments on the fly. A multi-channel soundtrack was created for this film, in part by the technology-obsessed celebrity conductor Leopold Stokowski, who recorded an optical track for each section of the orchestra, resulting in nine separate soundtracks, which he then mixed into four master optical tracks. Fantasia initially failed at the box office, and “Fantasound” was never recreated.

Stereo sound, dating from first two-channel audio experiments in Paris in 1881, came to Hollywood via 20th Century-Fox’s development of CinemaScope. The Robe (1953) was the first four-track stereo CinemaScope film to go into production, and the first released (although Fox’s How to Marry a Millionaire, 1953, was completed before it). This epic used true stereophonic recording — not only music, but also dialogue. The Robe featured three-channel stereo, plus a fourth mono surround channel for special effects employing multiple-microphone directional sound, such as footsteps of Roman Legions marching from right to left; thunder, wind and rain in the crucifixion scene; and an early use of off-screen voices.

Stereo initially failed to transform motion picture soundtracks and, after a spate of films, its use in non-music or non-effect sound virtually disappeared, until the 1975 introduction of Dolby Stereo Optical Sound. CinemaScope too suffered demise, although the anamorphic type lenses that made it possible continue in use today. Most studios provided some music in stereo, but generally recorded voices and effects in mono, creating some unusual sound/screen combinations.

One legacy of CinemaScope pictures was the extended 20th Century-Fox musical fanfare. Moviegoers were accustomed to arriving and seeing a curtain closed across the screen. When the film began, the curtain would grandly and slowly sweep open while the studio logo was displayed and its identifying musical accompaniment played. Theatre curtains across the country were automated to be open when a standard Academy ratio picture began, but with the arrival of CinemaScope and its much wider screen, the curtains could not fully open by the time the logo ended and the title appeared. It would have been impossible to change the speed of curtains opening in thousands of theatres just for CinemaScope, so the solution for Fox was to extend the screen time of its logo. To match the extra seconds, the music also had to be longer, so its composer and Fox’s musical director Alfred Newman added the grand notes that became the signature sound of 20th Century-Fox films.

As for some of the other pressing myths and questions surrounding Hollywood’s transition to sound, John Gilbert, “The Great Lover” of Greta Garbo both on and off-screen, had a voice probably quite well-suited to sound recording. The sudden demise of his career had much to do with the fact that he was reportedly detested by his MGM boss, Louis B. Mayer, who may have engineered Gilbert’s downfall. A Century of Sound demonstrates Gilbert’s vocal ability well in the “Hollywood Stars and the Transition to Sound” special feature on The Beginning disc.

This feature also includes a revelatory comparison of Laurel and Hardy skits. First, in a 1928 silent short, Should Married People Go Home?, Stan and Ollie take two lovely young ladies to a soda fountain for refreshment, but only have enough money to pay for three sodas —“misunderstandings and comic transactions ensue” using intertitles. A year later, 1929’s Men O’War short shows them doing the same bit, with the same cast of characters and same lines — only with recorded voices. The comic effect is the same; not only did their vaudeville-based routines work with or without dialogue, but their individual voices perfectly fit their personas.

Having completed the monumental labor of love that is A Century of Sound, Gitt will not be participating in the forthcoming last volume of this trilogy, although UCLA and the Rick Chace Foundation will oversee the production. The on-camera authority for the third part will be Ioan Allen, senior vice president of Dolby Laboratories, who obviously has a high standard to hit.

The spanner in the works of this grand project, if there is one, is copyright. The studios and stars, rightly recognizing the value of this project, granted rights to clips, soundtracks and images. The caveat is that the sets cannot be sold to the public, but can only be gifted to appropriate educational institutions and industry organizations. For more information on A Century of Sound, including its availability, please e-mail centuryofsound@cinema.ucla.edu.