by Kevin Lewis

Many picture and sound editors have cited Blow-Up (Blowup in the UK, 1966), directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, as a major influence on their methodology and their editing principles. The film inspired such directors as Francis Ford Coppola to create You’re a Good Boy Now (1967) and The Conversation (1974), and Brian De Palma to make Blow Out (1981). There are even editing and story elements of the film in Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969), Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1982), and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999). With its depiction of voyeuristic tendencies, Blow-Up is a good companion to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954).

Antonioni, after creating such penetrating intimate psychological Italian dramas as L‘ Aventura (1960) and La Notte (1962), confounded even his fervent admirers with this nonlinear, explosive drama, which was the equivalent of a gusher erupting from a manhole on Carnaby Street. As the film’s director, co-writer and uncredited editor, he chose the revolutionary rock music and fashion culture in post-austerity London for his first English-language film. Antonioni was nominated for the Academy Award for his direction and his original screenplay (co-penned with Tonino Guerra and Edward Bond), although the film acknowledged the short story Las Babas del Diablo by Julio Cortazar as its inspiration.

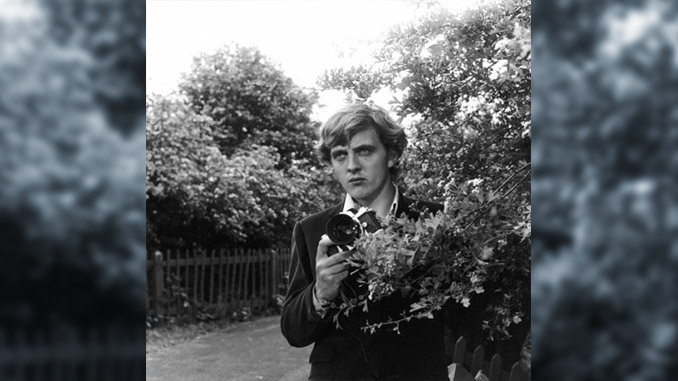

After 40 years, this manifesto of the emerging baby-boomer generation still holds its mystique. Though the film used the red herring of a jaded photographer, Thomas (David Hemmings), accidentally photographing an embracing couple in a lush London park––and then discovering it may be a murder in progress––that was just the hook which kept the audience hanging. Critics and audiences suspended their belief in a linear story because the director treated them to an Andy Warhol-like world peopled with tabloid supermodels, rock musicians and fashion designers on a documentary-like canvas.

Mainstream audiences descended on art house cinemas to see the then-novel full frontal nudity in a menage a trois romp (with Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills), scored by the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?” in the photographer’s studio.

The fashion layout session has been endlessly copied in films and haute couture commercials. MTV videos also copied many of these editing devices.

The film managed to slip into US theatres in December 1966, just ahead of the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) new rating system, which took effect the following year. In fact, Blow-Up was so controversial, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer had to release the film without an MPAA production seal of approval (the equivalent of an approved rating) under an unused subsidiary, Premier Films.

Ironically, neither the jump-cut editing, replicating the photographer’s relentless clicking of the camera, nor the soundtrack, which used rock music by the Yardbirds and jazz by Herbie Hancock as both a comment on the action and a narrative device, were cited at awards time. Blow-Up was produced at the British studio of MGM and Frank Clarke, who was the studio editor, with such upholstered Elizabeth Taylor romantic dramas as Beau Brummell (1954) and The V.I.P.s (1963) among his credits, was the nominal editor. But it was well known that the uncredited Antonioni was really responsible for the cutting. Indeed, Blow-Up is constructed like other Antonioni masterpieces.

Richard Peña, program director of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, associate professor, Film, School of the Arts at Columbia University, and an expert on the director, concisely sums up Antonioni’s editing principles: “Antonioni’s editing style often avoids temporal/spatial connections between shots, or associative links á la [Sergei] Eisenstein. His combinations of shots are often startling, not because they seem to be without distinct meaning, but because they offer too many possibilities for interpretation.”

The fashion layout session with supermodel Veruschka, where Thomas (based on real-life celebrity fashion photographer David Bailey) literally seems to be using his camera as a sexual weapon in jump-cut fashion, has been endlessly copied in films and haute couture commercials. MTV videos also copied many of these editing devices.

As for that ending, repeated viewings reveal some resolution. Blow-Up never literally resolves its plot. Like Thomas the photographer, the viewer is led to believe that a murder has occurred, but the evidence disappears––literally. The body is removed, no one corroborates the story, and Thomas doubts his sanity. When he later sees a group of mimes enact a tennis game, he actually hears the invisible ball hitting the imaginary rackets, and at one point picks up the fallen “ball” and hands it to one of the players.

The film managed to slip into US theatres in December 1966, just ahead of the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) new rating system.

Perhaps the answer to the mystery of the film is in the last scene, when Thomas stands in the park, a mere figure in the landscape, and disappears before our eyes, leaving the empty park as what it always was––nature, devoid of man. The world goes on, with or without us. Only then does it seem logical, in an Edgar Allen Poe sense. From the time we are born, we are alternately developing and decaying. Thomas is witnessing his own metaphysical death. His efforts to blow up the captured image, using the skills he has acquired throughout his career as a photographer and chronicler of life and experience, only frustrate him more. At a certain point, the portion of the photograph, as it becomes larger, appears more blurred and opaque.

Ultimately, the blown-up photo is just a series of dots, the same physical image as the punctuation mark known as the period––or in British parlance, a full stop.