by Tom Muschamp

When I was growing up, I moved from my suburban home in Reading near London to a small village in the southwest of England. In this new back-to-nature environment, I found myself seeking distractions. Before long, I was loading an 8mm camera with clunky cartridges and shooting my own shoestring productions.

Discarding the wise advice of my parents (“keep it simple”), I would try to push my productions as far as possible––complete with car crashes, chase scenes and badly choreographed staged fights. The results were usually disappointing, in part because I was running before I could walk. But I was also yet to discover the power of editing.

I had been ingesting a varied diet of movies around this time, thanks in part to my father, who had taught film studies in a university. Included in a mix of James Bond films and ‘80s blockbusters was an array of classics, from westerns to film noir. But the director who interested me the most was Alfred Hitchcock. I think it’s partly because his body of work was so distinctive––both thematically and stylistically, especially with his directorial trademarks and cameos.

This introduced a new concept for me as a budding filmmaker: Using editing to create the impression of an event without explicitly showing the specific action you’re attempting to depict.

But I was also fascinated by Hitchcock’s personal story. Born in Leytonstone, London, he’d worked his way up through the ranks, starting as a title card designer on silent pictures and eventually directing his own films. Hitchcock’s status as an A-list Hollywood director took many years to achieve. Along the way, his films developed and improved––peaking in the late 1950s with the consecutive releases of Vertigo, North by Northwest and Psycho. This was a career path that appealed to me as an aspiring filmmaker: hard work leading to success.

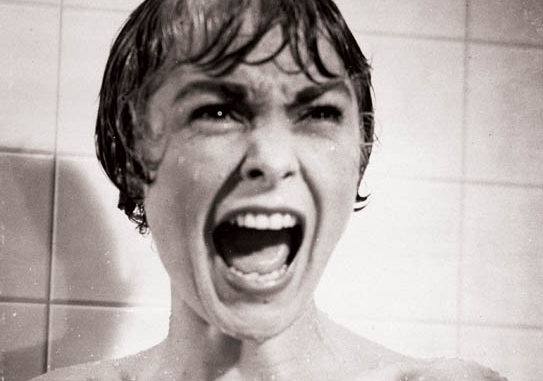

Of all his films, it was Psycho that struck a chord with me instantly. It was certainly a compelling and unconventional viewing experience, with Bernard Herrmann’s score striking fear from the top of the movie’s main titles. But Janet Leigh’s character’s unexpected demise in a shower had the biggest impact of all.

Viewing the shower scene for the first time, I don’t think I was aware of its status as one of the most famous sequences in cinematic history. Many authors and critics have analyzed its every detail since the film’s release. But as I watched intently, sitting on the rug in my parents’ front room, little did I know that my fascination (and later my career) in editing would be traced back to this moment in time. For me, that’s where it all began.

It was the first scene I had watched where I really noticed the editing. Of course, some editors will say you never notice good editing, but that’s another story. It was also the first time I’d seen editing used so powerfully. In a sequence that’s three minutes long, a series of fast cuts show images of stabbing knives, a screaming mouth, blood splashes and spraying water. Through this assembly of 50 shots, the unexpected butchering of a Hollywood leading lady is vividly portrayed––without ever showing a knife actually stabbing the character. This introduced a new concept for me as a budding filmmaker: Using editing to create the impression of an event without explicitly showing the specific action you’re attempting to depict.

Herrmann’s music for the shower scene is as famous as the sequence itself. And as most editors will affirm, music and editing are very much intertwined. Something happens when the perfect cue combines with the right set of images, and suddenly one is irreversibly bonded to the other. Psycho’s shower scene certainly made me aware of the relationship between the two. Before the deadly attack, George Tamasini’s editing pace is somber, even lingering, when a drawn-out five-second shot precedes the murder. But as the shower curtain is ripped back, the pacing becomes frenzied, mirrored in the famous string score with its frantic “stabbing” theme.

Above all, however, the Psycho shower scene was a great introduction to the fundamentals of editing. A good director, with an editor’s help, translates an emotion or feeling from page to screen by selecting and combining the perfect ingredients in the edit. And the success or failure of this process is judged by a viewer’s response to the finished product. The shower scene couldn’t be a clearer example of this process succeeding. Hitchcock is creating sheer terror––or the feeling of terror––by combining a well-judged selection of shots, of the right duration, in the right order, with perfect pacing and musical backing.

And it was that realization, as I watched and experienced terror, which finally made me aware of the power of editing. Looking back, I now trace my current career to the inspiration and fear I felt that day.