Story by and photos courtesy of Keith Reamer

The lights went up. The audience of eager editing students didn’t seem to know whether to weep or applaud. So they did both. In a few short hours, one of them, Mohammed Suliman, had taken several minutes of raw footage documenting a disabled shopkeeper and found the story of the local merchant’s improbable survival within the competitive retail environment of their capital city. The piece shone with a tone of playful defiance, capturing the essence of its subject. It was a brilliant cut, and very representative of the output of the members of the editing class I was conducting––6,000 miles from New York in Amman, Jordan.

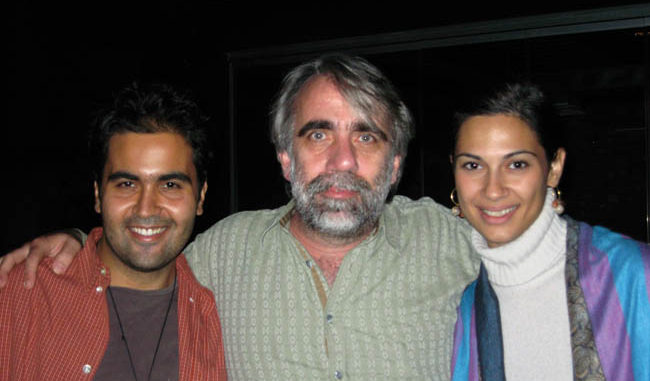

Not long before, I had been contacted by Carla Dabis, workshops officer for Jordan’s Royal Film Commission (RFC)–– through her sister, director Cherien Dabis, whose feature debut, Amreeka (2009), I had cut.

Working as part of a government mandate to strengthen the Jordanian filmmaking community through educational opportunities, Carla invited me to volunteer my services to teach an eight-day workshop for the RFC, “The Art of Editing.” Thrilled, I jumped at the opportunity and wrote a syllabus designed for individuals who knew the Avid but wanted to expand their creative approach to editing through an immersive, hands-on workshop.

The RFC is housed in a beautifully restored villa in the historic Jabal Amman district of the city, where I was greeted by Dabis and her supervisor––the charming and proficient Mohanned Bakri, who is responsible for all educational components of the RFC. A comfortable cottage on the grounds became my home for the next two weeks.

The following day I met my teaching assistants, Ayham Abu Hammad and Suliman, who, it turned out, were also going to be participants in the workshop. They had set up a training room of 12 Avids, one for each participant, with a video projection system. It was their job to assist the rest of the participants and keep up with the needs of my jam-packed syllabus. Throughout the long days of lectures, screenings and exercises, they never failed to keep pace with the demands of the workshop––both as TAs and students. The class, which also included four observers, consisted of advanced students, documentary filmmakers and working editors.

That night, we shot material to use for the first exercise: re-creating the famous Kuleshov Effect––a shot of an expressionless individual cut against various shots (coffee cup, intruder, happy child, etc.), demonstrating how the combination (not just the content) of images can generate a strong emotional response from the viewer.

On day one, I found myself wondering if my dialogue/hands-on approach would “travel well” into another culture. I needn’t have worried; minutes into my opening lecture, Dalia Al Kury, an observer and filmmaker, asked the first question regarding the creative role of the editor during the production phase of a film. That question led to another, and so on. Suddenly, we were in the midst of a fluid give-and-take, one that would continue until the end of the workshop.

But it was time to get cutting! In my introduction, I spoke about finding the story that lies within the footage, and listening to the film. With the re-enacted Kuleshov Experiment, the students immediately took this to heart; each devised a very different take on the available elements. One turned them into a contemplation of a hapless office worker, another into a crime re-enactment, a third into a humorous “Dear John” moment. The exercise revealed the uniqueness of each participant’s creative intuition and was a great ice-breaker.

For the next exercise, each participant was given a handicam. They were allowed two hours to find a subject and shoot it before returning to load it into their Avid. Before they began cutting, I gave a talk about screening material for the first time: taking notes, making sub-clips, asking questions of the footage, connecting the dots. Then off they went––and the results were surprising. Hammad devised a clever, comic piece about a person whose car seemed to have an assertive, noisy personality of its own. Islam Tahrawi created a hilarious depiction of a dry cleaner, and the passion he had for his work. Majida Kabariti made a charming film about two young girls attempting to recount the family history of their neighborhood. Mahmoud Zuaiter’s was about the shooting of a short film in production at the RFC. One of its highlights was the producer reflecting upon his own creative brilliance and indispensability to the project––an amusing reminder that filmmaking is filmmaking no matter what the culture.

Planning the workshop, I wanted the students to shoot and cut a dramatic scene. I wanted them working cooperatively and strategically––considering the needs of the editing process ahead. It needed to be something with drama, humor, subtext! I picked two dialogue scenes from Hitchcock’s Psycho. I changed the names of the characters, then gave the class a briefing on the scenes without revealing the source of the material. I broke them into two teams. Amongst themselves they cast and picked a director, a camera person and––something new to them––a script supervisor. I took those two supervisors aside and gave them a quick training session. One, Waleed Arafat, embraced how essential script notes would be to the director and editor, and executed an admirable set of notations.

Before they started editing, I talked more about reviewing and analyzing the performances and organizing their footage. Then I threw them a curve ball: All members of Team A would cut Team B’s footage, and vice versa. They would be dealing with each other’s production problems and would have to take ownership of solving them. With Team A, it was poor sound recording; with Team B, it was improperly executed script notes that provided little record of what had been shot. Of course, there was also the issue of dealing with the performances of non-professionals.

That exercise was revealing. In each scene, there were a couple of cut points that everyone executed almost identically; both were at the top of the action as the participants were setting up the geography of the scene. Beyond that, each student found his/her own approach to the material. Some played up the more unhinged takes of the Norman Bates character. Others focused on the internal drama of the Marion Crane character. One student, Yazan Meqdad, went off the grid and dazzled us with his inventive use of old-fashioned irises, isolating key elements within the frame.

Then we screened Psycho. It was a joy to listen to their reactions as they realized that the scenes they had just filmed and cut came from a world-renowned classic. In their own way, they had reinterpreted a masterpiece! And, without realizing it, they found another, deeper connection to their own creative voices.

Later, the students read Ralph Rosenblum’s description of the editing of Annie Hall before we screened it. A lively discussion followed about the idea of rewriting the story of a film in the cutting room and about how different Annie Hall would have been had someone else been its editor. We spoke about the flexibility of the editing process. They imagined what the results would be if a single film were to be cut over and over again by different editors––how it would change, with each new version reflecting its editor’s creative intuition. There was definitely a transformation taking place within the group; all were embracing the act of thinking like an editor.

We plunged into our final exercise: editing scenes from Amreeka, a film about a Palestinian woman and her teenage son, and the challenges they encounter when they move to America. Its director, Cherien Dabis, and producer, Christina Piovesan, were enthusiastically behind this workshop and allowed me to take a selection of scenes for the students to cut.

Because of the amount of material to choose from, each student had a custom-made schedule of scenes. They worked off the same bins and actual script notes that I used. As I had throughout the workshop, I stressed an intuitive, but investigative approach to the material, which meant I expected to see that everyone screened all their available material, used the script notes and generated their own editor’s notes as they began to cut.

There were many thrilling discoveries. One of the quietest students, Issam Alhafez––who had no professional film background and did not speak English––delighted everyone with his sure hand at cutting both the English and Arabic language scenes. Despite language barriers, he found a way to tune into the emotional core of the scenes. By the end of the workshop, he asked if I’d write him a letter of recommendation for film school. In a moment’s notice! Any school would be lucky to have him.

Then there was Saed Arouri, a talented television editor, who layered a lot of his cuts with heavy score (he was a particular fan of the feature 300). It was his crutch and he didn’t need it. Eventually, I persuaded him to drop the score from one scene and, to no one’s surprise but his own, he found himself delighted by just how fundamentally clear his work had been––without the sonic window dressing. It was a good lesson in having trust in one’s abilities.

And I will never forget the dedication and patience of our observers. One, Suha Ayyash, had been early to every class, working on her own, asking questions and listening. I wanted to make sure she and her colleagues got some hands-on editing time, so I had them take turns with the scenes on my Avid. They displayed a nimble, thoughtful touch with the material.

On day one, I found myself wondering if my dialogue/hands-on approach would “travel well” into another culture. I needn’t have worried.

One nagging point of uncertainty among the class was just how much creative initiative they should bring to their role as editor. How much control should they exert? How hard should they push for their own ideas? Where were the creative boundaries? We discussed the editors’ need to set aside their own ego, listen to their directors and understand, interpret and pursue the aspirations directors will undoubtedly have for the telling of their stories. We talked about the joys and stresses of the cutting room, responding to constructive criticism, collaboration and trust.

At workshop’s end, the students selected their favorite work for a film festival––hosted by the wonderfully resourceful and supportive Dabis––and, for a moment, we all basked in the enormous strides made by each member of the class. Finally, certificates were given, delicious food was consumed, and the students departed into the night, with––I hope––a greater confidence in their own skills and creative voice.

They’ve certainly given me the same! If these individuals––with their unique abilities and ambitions––represent the nucleus of the Jordanian film industry, I think Jordan has a lot of great cinema to look forward to. I volunteered for this assignment because I wanted to share my knowledge and experiences with a developing community of filmmakers. I wanted to teach and––as it turns out––I wanted to learn. I hope I have done both. But it’s only the beginning. And I plan on returning again…soon.

During the course of the workshop, Saed began following the events with his camcorder. From this material, he created a short film documenting the experiences of my visit and our class. It can be seen here.

Note: The Jordanian Royal Film Commission is a great resource for its country’s filmmakers, but its film library does not meet the needs of the community. The commission would be thrilled to receive donations of DVDs of films cut by Editors Guild members. You could also include a PDF file of cutting notes for your title. Your contribution would help forge a direct, mentoring relationship between the membership of the Guild and the educational mission of the RFC. For more information, I can be contacted at klredit@verizon.net.