By Michael Kunkes

From the moment Tad Marburg––Chairman of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Public Programs and Education Subcommittee of the Science and Technology Council––asked the audience members at the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre to turn their cell phones off with the codicil that “Ringtones are okay if they are interesting,” everyone knew it was going to be an evening of fun and nostalgia.

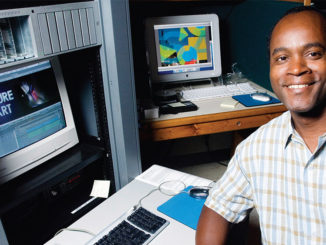

Last month, an audience of sound professionals and movie lovers, gathered for the culmination of the council’s “Sound, Camera Action” series, entitled, “The Sound Behind the Image.” The evening was divided into two parts: an exploration of some of the most groundbreaking films in the 80-year evolution of sound effects, hosted by Oscar-winning sound designer Ben Burtt; and to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the release of Star Wars, a panel discussion with key members of the movie’s sound team, led by the evening’s host and moderator, 19-time Oscar nominee and Academy Governor Kevin O’Connell (recordist on The Empire Strikes Back).

After looking for a long moment at the huge golden Oscar that dominates the Academy Theatre’s stage, O’Connell said, “What did I ever do to you?” drawing a big laugh from the audience. He then introduced Burtt, who presented clips from seven landmark films, each of which, he said, inspired him in his own career and helped create the rich artistic history of sound effects. Some of that commentary follows:

The Adventures of Don Juan (Warner Bros., 1926) “Shot as a silent but with Vitaphone orchestra and some rudimentary sound effects, especially in the climactic swordfight; this is the movie where sound mixing and effects were born.”

Tarzan and His Mate (MGM, 1934) “Tarzan’s yell was the most recognized sound effect of that generation. It’s a palindromic sound, one that sounds the same backwards as it does forwards. There are all kinds of stories about how it was achieved, but the most common one is that the first few notes were sung, then spliced together. A copy of that sound was then reversed and spliced onto the original sound. It’s an old sound editors’ trick. There was no music score in that movie, just sustained suspense and action with sound effects and great ambience. Also, the idea of Cheetah clearly communicating content and information just by using sound was really a breakthrough at the time. He was the first R2D2––a character that doesn’t speak English but can communicate and act.”

Flash Gordon (Universal, 1936) “Sci-fi provided sound effects editors a free field to experiment in. I loved the sounds they gave to the spaceships, with those strange electrical buzzings; there was no public consciousness in those days about what a rocket should sound like. Flash Gordon opened my mind to the fact that you could take a sound from somewhere else (mostly 1931’s Frankenstein), impose it on a spaceship, and it could work quite effectively.”

War of the Worlds (Paramount, 1953) “An electric guitar, which was pretty new as a popular instrument, was used to create the sounds of the Martian ray guns and cyclical feedback effects. Every sci-fi weapon today, including the lasers in Star Wars, can be traced back, at least in spirit, to War of the Worlds, which won Loren Ryder an Oscar.”

Shane (Paramount, 1953) “One of the most influential films when it came to gunfire, Shane started a tradition of big gunshots that has been picked up by Bonnie and Clyde, Dirty Harry, the Bond films and even Indiana Jones. George Stevens had been in the war and wanted to portray the power of guns. He slowed them down, and mixed in cannon fire. Then, to make the gunshots seem big, the violence would be preceded by something that would be very quiet for a long time, making effective use of floorboard creaks and the chink of spurs. Suddenly, when the fight begins, the gunshots seem much louder. It’s a good lesson for sound editors today to learn.”

Lawrence of Arabia (Columbia, 1962) “When we talked about what the score and sound for Star Wars was going to be, Lawrence of Arabia was brought up many times because of its sweeping romantic cues and big images. George wanted Star Wars to have a grand orchestral score like that. The rest of the track is all organic, realistic, articulated sounds––as you would expect in a Middle East war––and that’s how George wanted Star Wars to sound.”

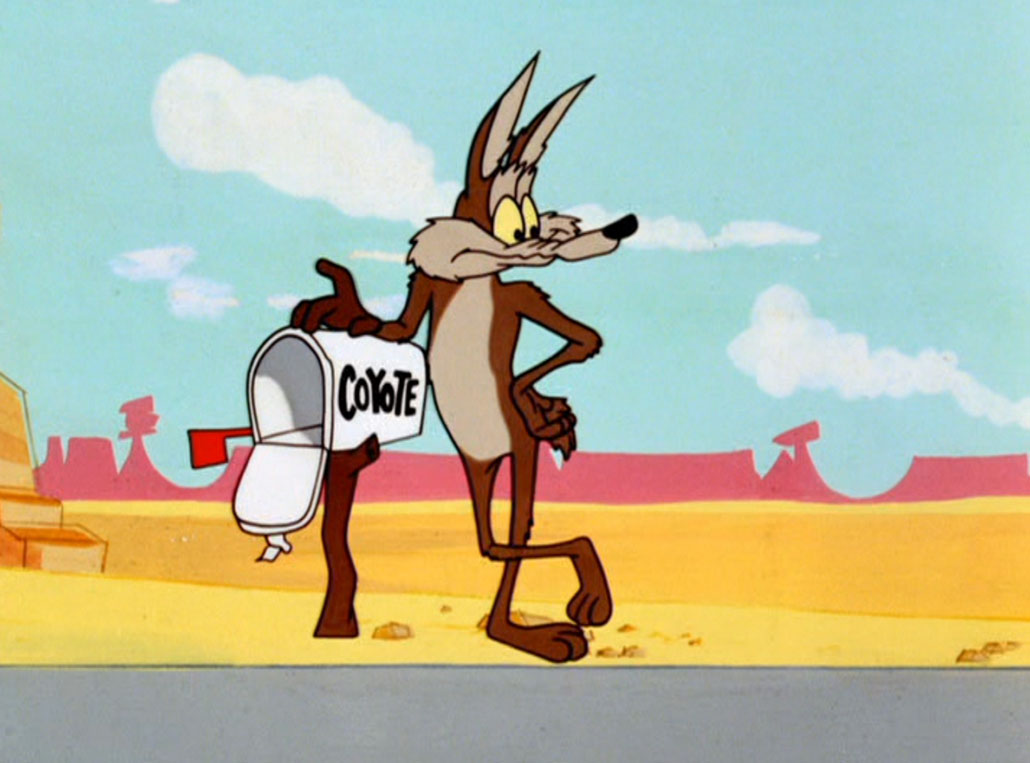

Wile E. Coyote (Warner Bros. cartoon) “Most cartoons used musical instruments for accents, but these films explored the power of real world sounds when they were combined with comic moments. It shows that the most effective moments are achieved when you find that real sound that works.”

After Burtt’s talk, O’Connell then introduced the evening’s panel, made up of Burtt, Academy Award-winning sound editor Richard Anderson, and Oscar winning mixers Don MacDougall, Steve Maslow, Gregg Landaker, Gary Summers, Gary Rydstrom, along with Donald C. Rogers, sound technical director and fellow Academy Governor. What follows are some excerpts from that panel, which concluded with a clip from one of the last few surviving original Dolby “A” prints of Star Wars.

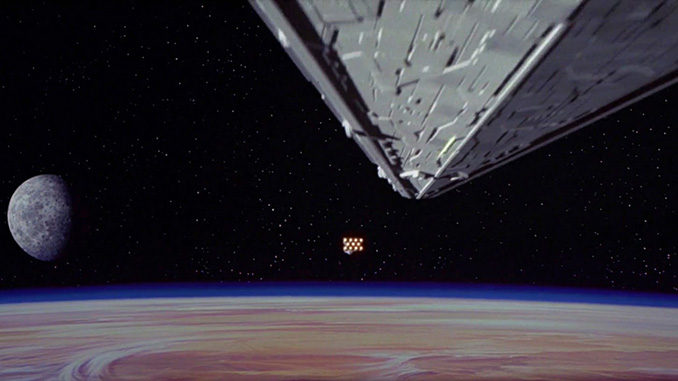

O’CONNELL: Don, you were the music mixer on Star Wars. Did you think it was the coolest thing on the planet, or corny?

MacDOUGALL: When that Star Destroyer came on the screen for the first time, I went out and bought 10,000 shares of Fox stock [laughter]. Seriously though, when we finished the dub, I told George Lucas that the only way to hear this was in 70mm six-track. And he said, “Well, the world isn’t going to hear it like that, because we’re only making 24 prints.” It’s a shame the world can’t here that sonority today.

O’CONNELL: Donald, you were the Technical Director at Goldwyn Studios. Why was Star Wars mixed there instead of Warners?

ROGERS: In late 1976, Landaker, Varney and Maslow were working with Martin Scorsese and Robbie Robertson on The Last Waltz at Goldwyn. One day, I got a call from Gary Kurtz, who told me that Clint Eastwood was kicking us off the dubbing stage at Warners, and asked could we finish our movie at Goldwyn. I went to Robertson and Scorsese, who told us we could work there––but only if we could come in at 7:00 p.m. and be out by 7:00 a.m. every day. I then asked Don MacDougall, who was the scoring mixer at Goldwyn, if he would do the night work. We still had no dialogue or effects mixer, so I borrowed Ray West from Ryder Sound and got Bobby Minkler to do the sound effects.

“[The Millennium Falcon] was recorded from a 1929 Beech Travelaire plane, which used something called an inertia crank to start the engine.” – Richard Anderson

O’CONNELL: Richard, weren’t you the guy who lit himself on fire on the Foley Stage doing a prop sound?

ANDERSON: Ben and I used to make student films together at USC. He went to work for George and I was working on low-budget features for Roger Corman and others. Typical of what I used to do was when I found in the trash some ADR that John Wayne had recorded and turned it into an insect voice on Hollywood Boulevard, which was Joe Dante’s first feature, I believe. Later on, I was working at Gomillion Sound, the Star Wars crew came in to mix the Death Star battle, and I ended up doing all the lasers and explosions. So, before they got the opticals of the battle, to get the flow for the cutting, we used dirty dupes of old World War II aerial battles. You’d see a ship go by being chased by a German Stuka, but of course we gradually replaced those shots.

O’CONNELL: Greg, one day you asked me, “Hey buddy, you want to come over here and pan a couple of TIE fighters?” And I said, “Yeah, let me do it.” Well, I did the first one exactly right, while the second one wasn’t even close. I was about to do it the third time when George walked in and stood right behind me. You leaned over and said, “It’s sweaty palm time, buddy, the pressure’s on now.” Well, I had never heard that before but my hands started pouring out sweat and I couldn’t do anything.

But my real question is, did you know how you were going to attack each project?

LANDAKER: Mixing was a performing art back then, and our computer was a No. 2 pencil. You rehearsed and rehearsed and rehearsed every reel. You knew the footage, and you memorized every single sound effect and what you wanted to do with it.

MASLOW: We would rehearse the entire day, taking meticulous notes, including where to insert dialogue. For example, if I was playing music at 110 decibels , I could come down gradually without feeling the pull. The other problem is that Gregg and I were both using the same four-track recorder, so if someone made a mistake or I was too loud covering dialogue, we would have to back up and jump back into the same recording at the same level at that moment.

“I told George Lucas that the only way to hear this was in 70mm six-track. And he said, ‘Well, the world isn’t going to hear it like that, because we’re only making 24 prints.’ It’s a shame the world can’t here that sonority today.” – Don MacDougall

O’CONNELL: Gary, you and I were recordists on The Empire Strikes Back, and then you went on to mix Return of the Jedi. Did you feel a lot of pressure to toe the mark on that?

SUMMERS: I was Ben’s assistant on Empire. Later, when we worked on Jedi, George kept saying he was going to bring in the hottest mixers in LA to do the film, so Ben and I just said, “OK, fine, we’ll just do the temp mixes.” So the day of the mix came, we looked around and no one was there, so Ben did the effects, I mixed dialogue and Randy Thom mixed the music––and that was how it happened.

O’CONNELL: I’ve heard the Millennium Falcon in a hundred movies since Star Wars. How did you create those sounds, especially the hyperdrive?

ANDERSON: It was recorded from a 1929 Beech Travelaire plane, which used something called an inertia crank to start the engine. It was a spring-driven motor that the pilot would wind up outside the plane. Then he would get in he cockpit, release the spring and start the propeller. Treg Brown at Warner Bros. also used it as the sound for the Tasmanian Devil.

BURTT: I bought an inertia starter on e-Bay last month, just to show you how crazy we all are.

O’CONNELL: What percentage of what we do is artistic vs. technical?

LANDAKER: It’s very much artistic––at least 50-50 but more like 70-30 [artistic to technical]. You can have all the chops in the world about faders and EQ, but it’s actually the fine balancing act of putting that movie together than makes it a reality. You have to have a feeling for that screen.

“Mixing was a performing art back then, and our computer was a No. 2 pencil.” – Gregg Landaker

O’CONNELL: I’d like to relate one George Lucas anecdote. After we finished Empire, we went to lunch at the Farmer’s Market in LA, and we all paid for our own lunches. After that, George bought us some sugar-free cookies––and if you think they taste bad now, you should have tried them back then. George said something like, “Thanks guys, you did a great job,” and he got into his car and left. We got into ours. I can’t even tell you the things Bill Varney said in that car. We got back to the studio, and sitting in front of each of our spaces was a very generous check from George thanking us. It was unbelievable.

O’CONNELL: We used to do the foreign and airline versions. Do you think we are headed for the iPod version of mixing?

LANDAKER: I think we’re already there. I can just see a bunch of mix teams sitting over the console with those little ear buds.

SUMMERS: What we do hasn’t changed. Only the tools have changed, most of the redundancies have been eliminated and technology is opening new creative avenues. You guys had to match every time to punch in, where we can now go through and touch up little details and focus more on the small things. The downside is that some people get locked into that and never make a decision. Personally, I only embrace the things that help me serve my client and make creative decisions for them.

MASLOW: I still find that the weak point in film is badly recorded dialogue. Short of looping, there’s nothing you can do with a poorly recorded track to enhance the quality. And how many directors like to loop?