by Peter Tonguette

Some filmmakers might wonder about the cinematic possibilities of filmed theater. After all, how can a movie version of a work conceived for the stage possibly compete with the excitement, pyrotechnics, and sheer kinesis of so much content today?

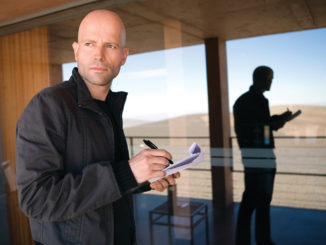

Picture editor Andrew Mondshein, ACE, has no such reservations.

Mondshein was a longtime collaborator of legendary filmmaker Sidney Lumet, who, as the New York-based, Academy Award-nominated editor tells it, was persuaded that few things in cinema were as fascinating as a well-timed close-up.

“Sidney used to say, ‘There’s nothing more interesting to audiences than the human face,’” said Mondshein, who, after working as an assistant editor in Lumet’s cutting room, served as the editor of several of the director’s films, including the acclaimed “Running on Empty” (1988). “He was never intimidated by a theatrical piece, and he did a number of great films that were plays first.”

Mondshein’s intuitive grasp of the potential of stage adaptations came in handy when he received the invitation to edit “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” a powerful, scintillating new adaptation of the Tony Award-nominated 1982 play by the Black playwright August Wilson. Directed by George C. Wolfe, the film stars Viola Davis as the real-life Gertrude “Ma” Rainey (1886-1939), a legendary African-American blues singer whose boundary-pushing recordings and inimitable performance style made her a source of considerable influence.

The film, which began streaming on Netflix on Friday, transports viewers to 1920s-era Chicago, where Ma Rainey is slated to make a new record. Prior to her arrival, the musicians who make up her band have congregated in a studio rehearsal room. Notable among the group is a tempestuous trumpeter named Levee, who is played, in his last screen appearance prior to his death from colon cancer in August, by “Black Panther” star Chadwick Boseman.

Among the producers of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” is Denzel Washington, who made the initial contact with Mondshein — despite the fact that the two had not worked on the same film since 1986, when Washington appeared in, and Mondshein edited, Lumet’s political drama “Power,” co-starring Richard Gere and Gene Hackman.

“I was picking up groceries from a local farm, driving down the road, and I got a call,” Mondshein said. “A voice on the other end was that very distinctive voice: ‘Hey Andy, it’s Denzel.’ We didn’t actually know each other. I pulled over to the side of the road and I said, ‘Hey Denzel, how are you?’ We started talking about the story and the project.”

Then Mondshein read screenwriter Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s adaptation of Wilson’s play. “You’re always desperately looking for that combination: a powerful story, beautifully written, amazing dialogue, with fully fleshed-out characters, and then a cast of just brilliant, brilliant actors,” he said. “This is the kind of project that you dream comes your way.” Mondshein flew to Pittsburgh, where the film was to be shot, to meet with Wolfe, whose work in theater and film he had long admired. “We had a terrific meeting, connected both personally and on the essence of the story, and I got the job,” Mondshein said.

Early on in the process, the editor and director were both conscious of balancing a need to enlarge the film’s canvas while maintaining the hothouse atmosphere of the rehearsal room in which Ma Rainey and Levee eventually come to loggerheads. For his part, Mondshein embraced the challenge of focusing on a small group of characters who spend much of the story in a relatively confined space. “You lean into them because you’re not consumed with the exterior world,” Mondshein said. “It’s their interior world, their history, the depth of their individual characteristics and character that comes into greater focus.”

In other words, what the film lacks in breadth it makes up for in depth. “When you look at a film that has an enormous scope cinematically, incredible vistas for visuals, that becomes a significant element in what you’re trying to communicate,” Mondshein said. “With this material, there was so much to find internally—to stay focused on the inside and the interpersonal drama and dig further and further into each of these complex characters.”

By adopting an almost-musical cutting rhythm even during non-musical sequences, Mondshein kept the film lively during stretches when audience interest had the potential of sagging. “There’s a lengthy 10 minutes early on when you’re in the band rehearsal room, and it had the potential to wear out its welcome,” he said. “George wanted to grab the audience and get them right inside the conversation, make them a part of the band. That was the great directorial approach that allowed us to just dive in and not worry that we were being too theatrical.”

Collaborating with cinematographer Tobias A. Schliessler, Wolfe deployed multiple cameras that whipped around from one actor to another in the rehearsal room. “He shot it to have that kind of crackle to it,” said Mondshein, who was given sufficient coverage to bounce between reaction shots of various band members. “One of the things that someone told me early in my editing career was to cut for the subtext, not the text,” he said. “Oftentimes they align, but many times, the reactions of other people to what’s going on that, in the action/reaction world of editing, reveal the moments you are desperately searching for.”

Of course, sometimes the best thing to do is not to cut. For example, the opening scene presents Ma Rainey performing in a tent in Georgia. Although some versions of the scene included reaction shots of Rainey and the musicians onstage, Mondshein and Wolfe ultimately decided to keep the focus on Rainey and the audience, which is in the palm of her hands. “In that instance, what we were trying to do editorially was depict Ma in her most captivating environment,” Mondshein said. “She’s like a preacher: The audience interacts with her, and she feeds off of that. We tried it with cuts to the band, but that wasn’t the story yet, so we kept it between her and this audience.”

Last summer, while Wolfe was shooting in Pittsburgh, Mondshein and his team — including associate editor Christopher Rand, first assistant editor Gordon Holmes, and ERA Kafayat Adegbenro — worked on their own in New York. “George was not interested in even looking at cuts along the way,” said Mondshein, who discussed the possibility of remote editing with Wolfe, but the director was not at all interested — at least last fall, before the coronavirus pandemic upended postproduction around the globe. “He said he definitely did not want to do it,” Mondshein said. “He said, ‘I have to be able to work right there with you all the time.’ Directors are different: Some like to come in consistently, some like to give noes and then go out and let you implement them. After all these years, I’m pretty flexible in how I can work with different directors as long as, most importantly, you’re seeing the material in a parallax view with the director.”

Once Wolfe sat down with Mondshein, the two found they were simpatico, even as early as the screening of Mondshein’s first assembly. “The first cut is generally a low point for the filmmaker—I laughingly say, ‘If you’re not suicidal, it’s a success,’” Mondshein said. “But when I showed George the whole film, he looked up at me and said, ‘OK, good, good. I’ll be honest with you: That’s the first time that I’ve been able to make it all the way through a first cut of any film that I’ve directed.’ I took that as a good sign!” Wolfe and Mondshein continued to hone the film through early 2020. Many elements were finessed, but the underlying architecture of the adaptation of Wilson’s play remained intact. “There was a real baseline of an incredibly written story,” Mondshein said.

A screening was held in February, but just weeks later, the entire industry — the reluctant Wolfe included — went remote due to the pandemic. “Most of the picture editing was done,” Mondshein said. “It was just some fine-tuning and a lot of ADR. And George did embrace it, finally.”

In the end, “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” sings not just because of the words of Wilson, the directing of Wolfe, or even the editing of Mondshein. At its heart are a pair of spectacular performances, by Davis and Boseman. “Both of them give you what you long for as an editor: great performances, from all different angles. You have the flexibility of telling it cinematically the way you want to tell it because they are consistently strong, and at the same time, they give you variations in performances that are subtle and authentic,” said Mondshein, who, like most of the world, had been unaware of Boseman’s illness until the announcement of his death.

“It is an almost unimaginable tragedy,” Mondshein recalled. “When I first saw Chadwick on-screen, I said to George, ‘Boy, he’s thin. Is this for another part?’ George said, ‘I don’t think so. I think he just wanted Levee to be really sort of gaunt.’” The editor added: “We had no idea. I think people will see that he had an acting range that he had only begun to show the world, and that this character is both different from anything he had done and brilliantly unique.”