By Peter Tonguette

Early in Hal Ashby’s 1973 drama “The Last Detail,” a trio of sailors share a meal.

Petty Officers Buddusky (Jack Nicholson) and Mulhall (Otis Young) are in the midst of the first leg of a trip during which they aim to combine business and pleasure. Officially, the two have drawn orders to accompany a young sailor, Seaman Larry Meadows (Randy Quaid), to a naval prison in Maine, where the glum-faced young man is to serve an eight-year term for pilfering $40 from a polio contribution box. Unofficially, the three of them intend to take a good, long while to make their way to Maine, planning to raise a lot of hell along the way.

In one of screenwriter Robert Towne’s signature scenes, Buddusky, Mulhall, and Meadows are seated in a diner. Cinematographer Michael Chapman’s camera followed a waiter walking from the kitchen with their orders — Meadows has requested a cheeseburger with sufficiently melted cheese — and settled on a wide shot of the three in their booth as the plates are set down. But it was picture editor Robert C. Jones, ACE, who added the touches and transitions that brought the scene to sparkling life.

Jones held on the wide shot even after Buddusky, nosily lifting up the bun on Meadows’s burger, finds that his charge’s cheese is unmelted. Buddusky summons the waiter: “Melt the cheese on this for the chief, would you?” After Buddusky sends the burger back, Jones cut, for the first time in the scene, to a medium shot of Meadows, looking on hungrily at his chums as they chow down and ooh and aah over their food. Then comes a time jump: Just as Buddusky barks, “Hey, where these malts at?,” Jones wittily dissolved to a head-on two-shot of Buddusky and Mulhall simultaneously taking one last gulp of their malts. The scene ends with a cut to a reverse angle on a now-satiated Meadows: “It’s good,” he says, holding up his burger.

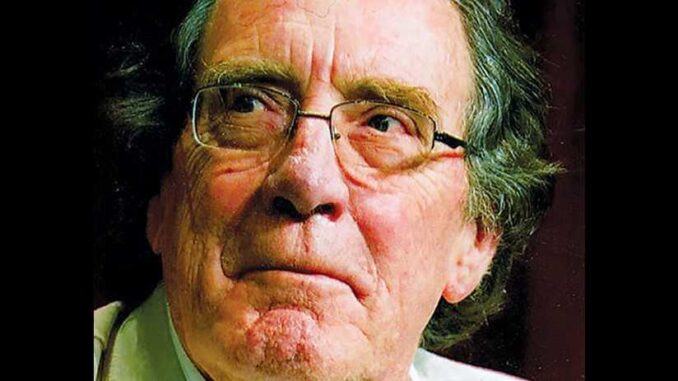

Such simple strokes of editorial invention were the hallmark of the films of Jones, who died on Feb. 1 at the age of 84. His survivors include his wife, Sylvia Hirsch Jones, and two daughters, picture editor Leslie Jones, ACE, and Hayley Sussman.

A Los Angeles native, Jones was born into a post-production family: His father, Harmon Jones, was an accomplished editor, receiving an Oscar nomination for cutting Elia Kazan’s “Gentleman’s Agreement” (1947), before becoming a director. His son was himself nominated for three editing Oscars — for “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” (1963), along with Gene Fowler, Jr., ACE, and Frederic Knudtson, ACE, “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” (1967), and Ashby’s “Bound for Glory” (1976), co-edited with Pembroke J. Herring — and took home a screenwriting Oscar, along with Waldo Salt and Nancy Dowd, for Ashby’s “Coming Home” (1978).

As an editor, Jones enjoyed multi-film collaborations with several important directors, including Stanley Kramer, Warren Beatty, and Arthur Hiller, but his most fruitful, and eclectic was with Ashby, for whom he edited “The Last Detail,” “Shampoo” (1975), “Bound for Glory,” and was among a consortium of editors on “Lookin’ to Get Out” (1981). Having been tapped by Ashby to contribute to work on the screenplay to “Coming Home,” Jones also produced the shooting script used for the director’s 1979 masterpiece “Being There.”

First and foremost, though, Jones was a gifted editor — praised for his speed and invention by his colleagues.

“He was probably the fastest editor I ever worked with,” picture editor Don Zimmerman, ACE, told CineMontage this week. Zimmerman served as an assistant editor under Jones on “Shampoo” and “Bound for Glory,” but was bumped up to picture editor on the Jones-scripted “Coming Home” and “Being There.” “He was just really brilliant and a great storyteller,” Zimmerman said. “He really had an incredible mind. . . . He instilled in me a whole sense of how to do things.”

Jones’s association with Ashby began on “The Last Detail.” Film scholar Nick Dawson, the author of the acclaimed biography “Being Hal Ashby: Life of a Hollywood Rebel,” said that Ashby was dissatisfied with the initial work done by the original editor on the film. Jones was brought in on short notice, ultimately molding the film into the masterpiece it became.

“Jones was starting from scratch,” Dawson told CineMontage this week. “It was a situation where time was of the essence. The work that he did was so quick and so good.”

Ashby, who had won acclaim (and an Oscar) as a picture editor himself, kicked off his directorial career with “The Landlord” (1970) and “Harold and Maude” (1971). Those classic films, edited by William A. Sawyer and Edward Warschilka, featured a flashier, more ostentatious style of editing in keeping with the spirit of the New Hollywood movement, something Jones moved away from. “You see in the films that Jones cut for him a greater simplicity in the editing that allowed the strength of the material to stand out,” Dawson said.

Jones’s sedate, contemplative editorial rhythms also added an extra dimension of melancholy to the sex farce “Shampoo,” starring Warren Beatty as George Roundy, equally sought-after as a hairdresser and Don Juan figure in the lives of a bevy of Los Angeles women in 1968, including Goldie Hawn, Julie Christie, and Lee Grant. “He and Warren hit it off, and he worked with Warren on almost everything,” said Zimmerman, who, with Jones, co-edited Beatty’s “Heaven Can Wait” (1978). Jones then edited the Beatty-produced “Love Affair” (1994) and, with Billy Weber, ACE, co-edited the Beatty-directed “Bulworth” (1998).

Confident in Jones’s ability to bring out the best in the footage he shot, Ashby gave himself permission to step away from day-to-day involvement in postproduction. “In simple terms, [Jones] freed him to be a director first and to be able to not feel a sense of obligation to be in the cutting room too much,” Dawson said. “It allowed him to sort of live his life a little bit: He’d finish production and hand off the film to Bob Jones. . . . He knew that the movie was in good hands.”

Yet Ashby had bigger plans for Jones, who was tasked by the director to get the screenplay for “Coming Home” ready to shoot. “There were a decent number of credited and uncredited writers on that film, including Ashby himself,” Dawson said. “Jones was somebody that he trusted. It’s a testament to his incredible abilities, and that rare combination of skills, that the film is so good.” After winning an Oscar for “Coming Home,” Jones wrote the script used during the filming of “Being There” (though Jerzy Kosinski, upon whose novel the film was based, received the sole on-screen credit). “The version of ‘Being There’ that was shot was Jones’s script,” Dawson said.

Ashby and Jones would eventually go their separate ways, but his demand as a top picture editor never abated. Jones also worked on Tony Scott’s “Days of Thunder” (1990) and Harold Becker’s “City Hall” (1996). In his capacity as a screenwriter, he penned episodes of Shelley Duvall’s acclaimed series “Faerie Tale Theatre.” In 2014, Jones received a Career Achievement Award from the American Cinema Editors.

“Bobby is the kind of guy who could do just about anything,” Zimmerman said.

And Ashby’s films lost a little of their magic in the absence of Jones, the man who was, for so long, his go-to editor. “I feel like he maybe thought it was a bit too easy — that it was kind of a bit of a cheat — to have Bob Jones as your editor,” Dawson said.