by Ray Zone

The B List

By David Sterritt and John Anderson

Da Capo Press

288 pps., paperbound, $15.95

ISBN: 9778-0-306-81566-9

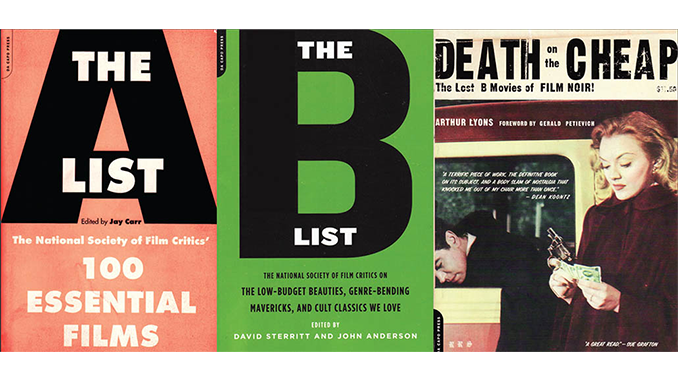

For several years now, one of my favorite books has been The A List, published by Da Capo Press in 2002. This book is edited by Jay Carr, film critic for The Boston Globe, and is a listing of 100 essential films by the National Society of Film Critics, with contributions by Henry Sheehan, Roger Ebert, Peter Travers, Dave Kehr, Andrew Sarris, Joe Morgenstern, Richard Schickel, Jonathan Rosenbaum and Carrie Rickey, among others. Carr wrote several contributions to the volume and each film critic picks out one of his or her favorite movies and provides some cogent observations as to its importance in film history.

As a classic and foreign film buff, what I like about The A List is its resolutely eclectic listing of old and new films. The titles run the gamut from Birth of a Nation (1915) and Metropolis (1927) to La Strada (1955) and Jailhouse Rock (1957) on up to Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Some of the very best discussions of classic foreign films like L’Atalante (1934), Children of Paradise (1945), The Seven Samurai (1954) and La Dolce Vita (1959) are to be found in this book. For me, there is no better way to prepare for viewing, or revisiting, a film than by reading intelligent discourse about it.

Now, after publishing The X List (2005), the National Society’s guide to “the sexiest films ever made,” Da Capo has given us The B List, edited by David Sterritt and John Anderson, with film critics’ picks and observations about “low-budget beauties, genre-bending mavericks and cult classics.” Here again is a tome that will set nicely on the shelf beside your movie collection and provide rewarding reading as a supplement to the film viewing experience. Divided into 11 categories of B movie, the films selected range from black-and-white film noir and “Technicolor Nightmares” of neo-noir to grindhouse/arthouse melodramas, science fiction, horror, road movies, wild westerns, political and rock ‘n’ roll movies to “perverse provocations” and the “transgressive chic” of midnight movies.

Arthur Lyons book includes a filmography of B noirs unlike any other listing of titles and includes many overlooked gems.

In their introduction, Sterritt and Anderson observe that the B movie itself was once “the Hollywood stepchild, the underbelly of the double feature, the scrambling lab rat of cinematic innovation.” They assert, “Today, it is a more inclusive category, embracing films that fall outside the mainstream by dint of their budgets, their visions, their grit and, occasionally––sometimes essentially–– their lack of what the culture cops call ‘good taste.’” Taste, the editors note, is “subjective, transitory and evolving.” It’s interesting to observe evolving cultural mores and the way that individual films stand as watersheds of changing taste and values. It’s also intriguing to see how older films may acquire or lose cultural meaning and impact over decades. All films, however, as Henri Langlois observed, merit preservation as markers of cinematic art and social signification. Certain genres, like film noir, created inherently out of the cinematic language of light and shadow, can evolve to speak powerfully to the contemporary world.

Not surprisingly, The B List begins with “Out of the Shadows,” a discussion of classic film noir and opens with J. Hoberman’s discussion of Detour (1945), director Edgar G. Ulmer’s greatest artistic achievement. Hoberman flat out calls Ulmer “a hero” and notes that Detour was produced on a rented soundstage in under a week. Hoberman also did his homework and mentions Peter Bogdanovich’s February 2, 1970 interview with Ulmer as published in Film Culture magazine (no. 58-59-60, 1974).

“Nobody ever made good films faster or for less money than Edgar Ulmer,” wrote Bogdanovich. “What he could do with nothing––occasionally in the script department as well––remains an object lesson for directors who complain about tight budgets and schedules. That Ulmer could also communicate with a strong visual style and personality with the meager means so often available to him is close to miraculous.”

Hoberman is very clear in delineating the importance of Detour to the B movie. “Detour isn’t just a masterpiece; it’s a veritable moon rock, a jagged chunk of the American psyche,” he writes. “Although never reviewed by The New York Times, this visually exciting movie should be a required study for all prospective independent filmmakers.” These remarks also point to another little masterpiece of film study published in 2000 by Da Capo Press, but still in print.

There is no better way to prepare for viewing, or revisiting, a film than by reading intelligent discourse about it.

Death on the Cheap: The Lost B Movies of Film Noir by Arthur Lyons is a seminal volume in the field. Lyons, a prolific author and the founder of the Palm Springs Film Noir Festival, recently passed away just as the latest (sixth) edition of the Festival was commencing. Death on the Cheap properly elucidates the origins of the film noir genre in the B production units of Hollywood. “It is important to understand,” writes Lyons, “that film noir developed as a style within the B crime film genre and ultimately developed into a genre itself.” His book includes a filmography of B noirs unlike any other listing of titles and includes many overlooked gems.

Sterritt and Anderson, too, emphasize the importance of Ulmer and Detour to the entire world of B movies in their book of lists. “Edgar G. Ulmer holds as important a place in American movies as directors much better known––see his inimitable Detour for Exhibit A,” they observe. “Don’t look for a formal declaration, or even an informal one, of what a B picture is. We’ve taken it in the broadest sense, referring to any and all movies made with modest means, maverick sensibilities and a knack for bending familiar genres into fresh and unfamiliar shapes.” This hearteningly eclectic sense reflects the vitality of B movie production as a continually evolving challenge to make the most of very little as an inherent part of cinema’s narrative grammar.