by R.J. Kizer

When did ADR start?” It was a simple question, and our director was fond of asking simple questions; “Is that the best you can do?” was one of his favorites. Everyone on the mixing stage knew the question was directed at me so they kept their attention focused on the job at hand, allowing me, and me alone, to bear the brunt of slings and arrows about to come my way. I replied that I did not know, but I knew that ADR was around in June 1979 — the first time I attended an ADR recording session. The great man grunted in noncommittal acknowledgment, and his attention returned to the temp mix already creeping into the 14th hour.

So when did ADR start? Post-synchronization of dialogue for motion pictures goes back to at least 1928 with the adding of dialogue to movies originally shot as silent pictures. The mechanics of achieving this evolved very quickly into what became commonly known as “looping” — a method that, by 1935, was employed throughout Hollywood. While the origin of the term is fairly self-evident (short segments of picture and guide track were each joined end to end, forming a loop), ADR is a little more mysterious. A quick search of the Internet will return “Additional Dialogue Recording” as a popular definition. Now, every ADR mixer and editor is quick to tell you that ADR really stands for “Automated Dialogue Replacement.” The Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) has been handing out awards for Best Automated Dialogue Replacement editing since 1983 (my emphasis).

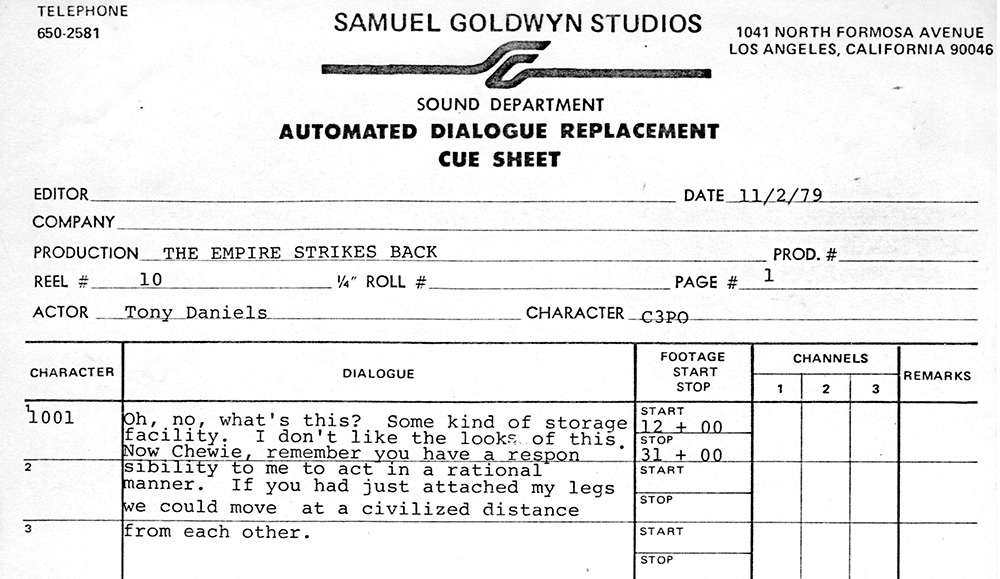

The scan of an ADR programming page for The Empire Strikes Back is dated November 1979, with the header information on the sheet reading “Automated Dialogue Replacement (see Figure 1).”

Yet, when I pursued my research into the origins of ADR, I discovered that, when first presented to the industry, the technique went by other names and initials. In 1969, ADR stood for “Automatic Dialogue Replacement” (my emphasis). It was also called “EPS” or “Electronic Post Sync.” In addition, the process was marketed as “Automatic Looping,” “Electronic Looping System,” “Auto-Loop,” and “Reverse-O-Matic Dialogue Replacement.”

ADR came about in response to the physical limitations of looping and the technical innovations of electronic machine control. As mentioned earlier, “looping” took its name from the mechanical process by which the task was accomplished — namely that the picture and the original guide track of sound were each edited into separate loops of equal length.

Being a loop, the picture and guide track would repeat over and over again. Once the actors felt they had captured the rhythm of the line, the recorder was turned on, and several readings would be recorded. When a good reading in terms of performance and sync was achieved, the recorder was switched off, and the next loop was threaded up.

This method of post-sync line replacement was very time-consuming and labor-intensive in its preparation. Each loop per cue had to be exactly the same length; any mistake would have one element becoming out of sync with the other. The “virgin loop” method required three loops to be prepared for each cue: picture, guide track and blank recording stock. (By the late 1950s, a low-budget alternate method was audio-only loops.) Each had to have a common start mark, as well as identification. Multiple characters in a scene to be line-replaced could require multiple black-and-white picture dupes. The nature of the playback and recording equipment mandated limitations to the physical dimensions of the loops. They ranged from as small as six feet, to as large as 150 feet. Anything shorter couldn’t be threaded on the playback machines; longer loops ran the risk of getting tangled and shredded in the gears.

As Emory Cohen, former vice president of operations at Glen Glenn Sound, described in an e-mail to this writer, “If there was a lot of looping to be done, the sorting of the picture and track loops in the machine room was crazy. Imagine the machine room with hundreds of loops in cans, boxes, on the floor — everywhere — and the same in the projection booth!” (See Figure 2.) Changes and alterations were both difficult and time-intensive to do after the loops were prepared. Combining or dividing cues required stopping the session and physically re-cutting the loops.

Additionally, the true art in the whole enterprise was in knowing the capabilities of the performers. There were actors who could handle a cue lasting a minute and a half, while there were others who could barely manage a simple phrase. With a long cue, if actors flubbed at the beginning of the line, they would have to wait for the loop to finish its route before trying another take.

Because all the recordings were made onto loops, there was no possibility during a session of playing back an entire scene to see how it all worked together. And almost to add insult to injury, physically cutting up a print required getting enough black-and-white dupes to cover all the characters, and getting them quickly. If the dupe of a scene was too dark to see the lips, a color reprint of the original negative would have to be ordered; another delay. Getting ready for a looping session often turned into a race against the clock.

By 1965, forward-backward machine control and insert recorders were introduced for re-recording. This new capability not only was a boon to post-production sound mixing, but it pointed the way toward loop-less looping. Some facilities were experimenting with rocking the system forward and backward over a specific line for purposes of line replacement. The American Cinematographer Manual, Second Edition (1966), had a lengthy section covering various aspects of sound recording and post-production. Near the end of the section on looping ran the following:

“Another system of line replacement that has been in use in several European countries, and is now finding some acceptance in the United States, is the ‘forward-backward’ system. In its operation, the sound and picture are not made into loops, but are run forward while recording a new dialog [sic] track, then reversed to a selected spot and run forward for either a review or another ‘take.’”

Journal of the SMPTE, September 1969, courtesy of AMPAS Margaret Herrick Library

At that time, the systems could only travel at sound speed. Once a specific area had been played, the operator had to stop the system and reverse it back to the start point of the cue. Sound speed forward, sound speed backward. It was hoped that in this modern age of circuit boards and transistors someone could devise a controlling mechanism to automate the process.

Here in Los Angeles, two gentlemen — Roy Swartz (an engineer at Glen Glenn Sound) and Carlos Rivas (of Rivas splicer fame) — created a post-sync dialogue replacement system that did not use loops of either film or track. Glen Glenn Sound obtained exclusive rights to the system and had it installed and operational sometime between 1967 and 1968. (Sadly, Mr. Rivas passed away in March 1967 and never saw his co-creation fully realized.)

As Cohen described it, “The system was electro-mechanical. The ‘interface’ to the ADR programmer was a thumbwheel for entering the actual start and stop footage of the line to be replaced, and a unique method of entering frames. It was a 19″x 19″ silver-anodized aluminum panel with two concentric circles of small (approximately 1/8″) holes (about 1/4″ apart), forming a circle about 15″ in diameter. Mounted in the center of the circle was a single arm, like the arms of a clock, that reached to the inner circle of holes. The circles of small holes were labeled with a frame number.

“Using the thumbwheels, and by inserting steel pins into the correct holes on the panel, the ADR programmer entered the feet and frames of the beginning and ending of the first line to be replaced, as shown on the editor’s session cue sheet.

“Sensors and relays behind the control panel sent start, stop, and record instructions to the projector, sound reproducer and recorder. The control electronics triggered a tone generator to [play] the three beeps at the correct place before the dialogue.”

The “automatic” aspect referred to the system’s removal of the need for human operation of such tasks as advancing the projectors, reproducers and recorders to the next event, cuing the actor as to the start point of the event, and having the recorder go in and out of record. Once the start and end points of a given line were entered, the controlling system would play and rewind and play and rewind, all the while sending audio cues (three beeps) to the actor to signal the start of the specific line, and it would continue until stopped by the operator.

When introduced, the system was originally called “Automated Dialogue Dubbing,” or ADD. (Imagine, we came that close to being called ADD editors…for real!) Cohen told this writer that he gave an oral presentation about the system to the Hollywood chapter of the SMPTE, but never submitted it for publication, thus explaining the lack of information about it in the printed record.

In fact, a search of Daily Variety archives did not turn up any article or advertisement about this new loop-free method. Within the first couple years of operation, someone at Glen Glenn Sound decided that Automated Dialogue Dubbing was not a good name. After all, the word “dubbing” could also be taken to mean re-recording (see sidebar, page 53). So Glen Glenn Sound rebranded its loop-less system as “Automatic Dialogue Replacement.”

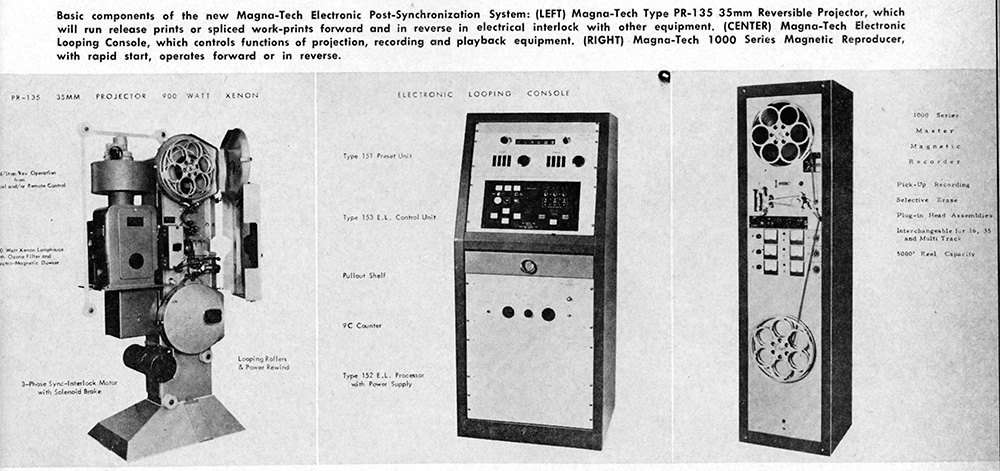

Meanwhile in New York City, Otto Popelka and his team at Magna-Tech Electronic Company (MTE), introduced their “electronic looping system” during Fall 1968. First installed at Manhattan Sound Studio on West 54th Street, the MTE system received a substantial description in an article published in the October 1968 issue of the American Cinematographer magazine (see Figure 3). Manhattan Sound Studio called its installation “Electronic Post-Sync.” The Magna-Tech Electronic system included not only the electronic controller but also a specially designed film projector and a magnetic film recorder that could run fast-forward or reverse by as much as 144 frames per second, while still maintaining synchronization. The recorder could do inserts accurate to one frame. Like Glen Glenn Sound’s loop-less system, MTE’s would automatically generate three audio tones prior to the start of the line to serve as a means of cueing the actor.

From the unidentified author of the American Cinematographer article: “It was pointed out that the Electronic Post-Sync System precludes the need for cutting loops and eliminates the editing of the track. Complete reels of the motion picture are run in synchronization with the full-coat magnetic film, on which the sound track is recorded, and transfer of the best takes is made to the third track of the same recorder. This track now has all of the final takes in sequential position and ultimately permits the screening of the picture and the final edited track in perfect synchronization.”

The MTE-developed system was rapidly adopted by sound facilities in New York City. According to Paul Zydel, one of New York’s ADR mixers, “When ADR first came to New York, it was called Electronic Post Sync. EPS never caught on; Hollywood didn’t accept the term…” (Sound-on-Film: Interviews with Creators of Film Sound by Vincent LoBrutto, 1994). Curiously, MTE advertisements always referred to its no-loop family of machines as an “electronic looping system,” even as late as 1989 (see Figure 4).

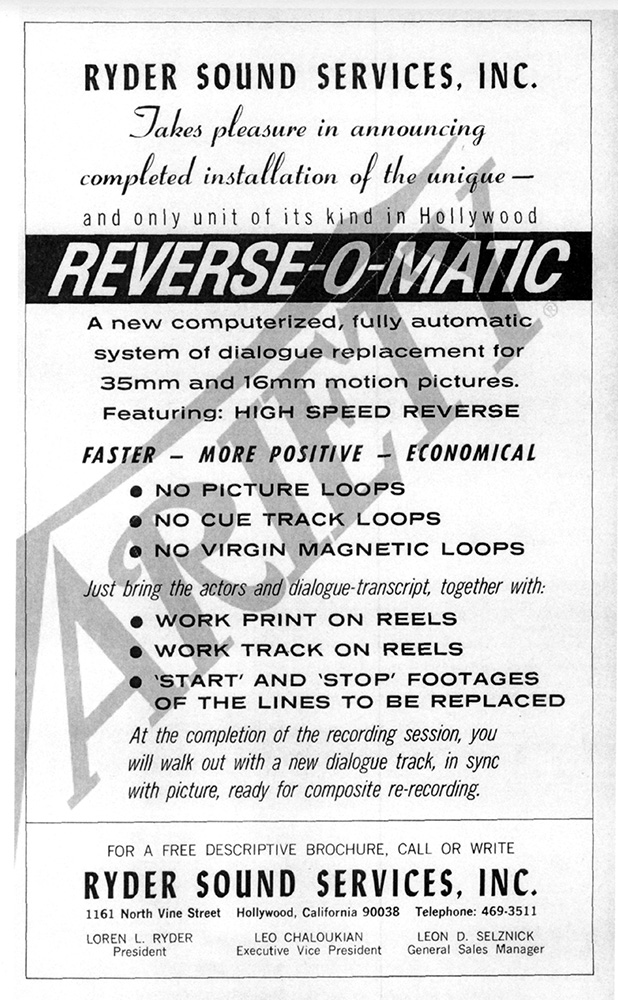

A few months earlier, on the West Coast, Ryder Sound Services was the first to install MTE’s “electronic looping system” in the Hollywood post-production community. A large ad appeared in the May 6, 1969, issue of Daily Variety announcing that Ryder’s “Reverse-O-Matic” system was open for business (see Figure 5). According to Leo Chaloukian, then vice president of Ryder Sound, the first producer to use the system was Roger Corman.

Two days later, another ad from Ryder Sound appeared in Daily Variety, also touting its new Reverse-O-Matic loop-free system, but this one led off with: “Ryder Sound Offers Automatic Dialogue Replacement System Called Reverse-O-Matic.” This ad is evidence that by May 1969, the term “Automatic Dialogue Replacement” was already a familiar one in Hollywood.

April 1970 saw Popelka and MTE receive a Class II Scientific-Technical Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for their “development of an electronically controlled looping system.” By the end of that year, Glen Glenn Sound purchased the MTE system for itself and, on January 19, 1971, took out an ad in Daily Variety announcing that it had two stages equipped for Automatic Dialogue Replacement, with a third to be ready in the very near future. What’s most interesting about the ad is the inclusion of the following: “And remember, we know more about what ADR can do because Glen Glenn Sound invented the Automatic Dialogue Replacement system” (see Figure 6).

But no matter what name was given to the system by various sound facilities (Electronic Post Sync, Reverse-O-Matic, No-Loops), in 1970 Hollywood the process was called Automatic Dialogue Replacement or ADR (my emphasis).

The 1970s saw the adoption of ADR systems throughout the industry. A press release from October 30, 1972, in Variety announced, “Todd-AO Corp….completed installation of an automatic dialogue replacement system and Foley stage in a ‘completely modernized studio.’” Just a few months later, Goldwyn Studios opened its Gordon E. Sawyer sound facility on January 25, 1973. Not only did it receive substantial coverage in Daily Variety, but the March 1973 issue of American Cinematographer ran a lengthy article describing the new stages therein: re-recording, sound effects recording (what we now call Foley) and ADR.

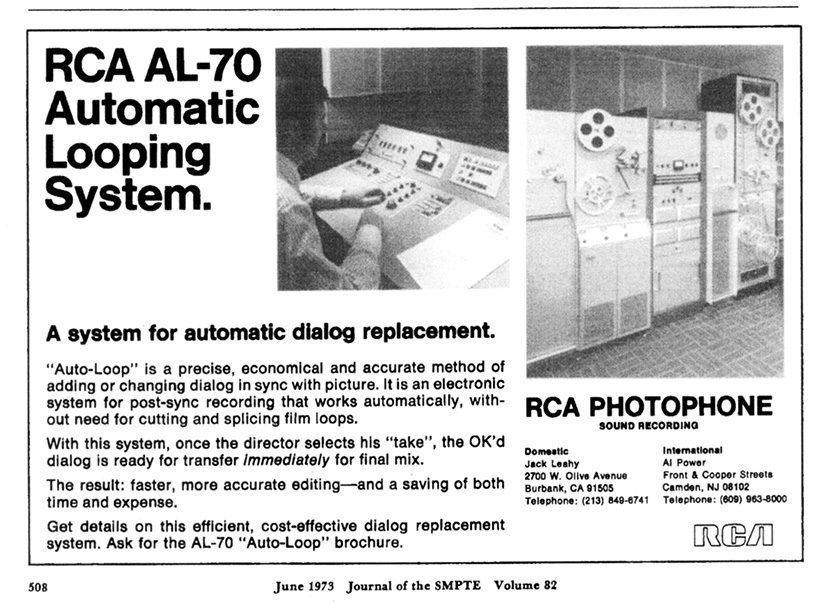

According to the article, “Incorporating the RCA AL-70 Automated Dialog [sic] Replacement system, the need for cutting and splicing film loops is eliminated. Its electronics counter system, computer logic and interlock motor system permits more precise and faster recording, with the added advantage of versatility… After pre-set footages have been programmed, actuation of the sequential push buttons — ‘rehearse,’ ‘record’ and ‘play’ — automatically control the total recording and monitoring functions.” (See Figure 7.)

There it is: Automated Dialogue Replacement (my emphasis); the term first appeared in print in connection with Goldwyn Sound in 1973. From that time onward, the “A” in ADR had two meanings: “automatic” and “automated,” with “automated” eventually winning the hearts and minds of ADR editors and mixers.

Another line in the description of the Goldwyn ADR system piqued this writer’s curiosity: “An automatic electronic pacer tone is provided which is electronically adjustable to the actor’s pace.” What was that all about?

Abandonment of looping continued apace as sound facilities upgraded their post-sync capabilities. Some would purchase the MTE system, others would purchase RCA’s. And a few facilities would march to their own drummer and build their own. According to ADR mixer Bob Deschaine, CAS, Gomillion Sound built its ADR-style system from scratch and had it operational by 1973-74.

A search of trade journal back issues shows that MGM had its ADR stage up and running by late 1974, Universal by 1978, The Burbank Studios (Warner Bros. and Columbia) by July 1978, and Saul Zaentz’s facility in Berkeley by 1980. ADR became the accepted nomenclature throughout Hollywood, and then the rest of the country; the New York term, EPS, faded away.

In looking back over the advertisements and articles introducing ADR, I am struck by how they all trumpeted that this new system of post-synchronization would eliminate the need for a lot of sound editorial labor. From the Magna-Tech Electronic ad that appeared in the September 1969 issue of Journal of the SMPTE: “The Electronic Looping System precludes the need for cutting loops and eliminates the need for editing of the track…. From this point the track is ready to go to a mix and no further editing is required [my emphases].”

From the American Cinematographer magazine October 1968 article about the MTE system: “Some of the advantages of the Electronic Looping System are self-evident. Except for the spotting of scenes, all editorial work is eliminated [my emphasis]. The recording produced is immediately ready for a mix, or preview.”

From the RCA ad in the June 1973 issue of Journal of the SMPTE: “It is an electronic system for post-sync recording that works automatically, without need for cutting and splicing film loops. With this system…the OK’d dialog [sic] is ready for transfer immediately [their emphasis] for final mix.”

And finally, from the Ryder Sound ad in Daily Variety, May 6, 1969: “At the completion of the recording session, you will walk out with a new dialogue track, in sync with picture, ready for composite re-recording.”

As it turned out, these promises of “no editing required” proved to be wildly optimistic.

In conclusion, I now have a better answer to my director’s original question. Here in Hollywood, ADR started between 1967 and 1968, with Glen Glenn Sound being the first to have a working system in place. In 1968, New York’s Magna-Tech Electronic Company introduced its electronic looping system, which was a full package of projector, recorder and controller. It became the model for all subsequent systems.

In Hollywood, the process was originally known as Automatic Dialogue Replacement, while in New York it was called EPS or Electronic Post Sync. Ryder Sound was the first Hollywood facility to install the MTE system, having its stage open and ready for business by May 1969. In 1973, Goldwyn Sound redefined ADR to mean Automated Dialogue Replacement, and the Hollywood sound post-production community came to adopt that as the “official” meaning, as evidenced by MPSE choosing that definition for its award category in 1983.

It’s not a quick, pithy answer, but it’s thorough.

The author wishes to acknowledge the generous help and guidance of the following individuals: Emory Cohen, Leo Chaloukian, Bob Deschaine and the late Marvin Walowitz. Also, this article would not have been possible without the resources of the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS).

Syncin’ in the Rain

Looping Goes to the Movies

There haven’t been a lot of movies about moviemaking. Of those few, even fewer depict a post-sync dialogue replacement session. Three that come to mind are Postcards from the Edge (1990, Columbia), Inside Daisy Clover (1965, Warner Bros.) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952, MGM).

Even though Postcards was released in 1990, and based on a 1987 novel, the post-sync session depicted in the film is staged more like an old-fashioned looping session. The film only shows the lead (played by Meryl Streep) rehearsing the line. She then engages in a lengthy conversation with the director of the movie-in-the-movie (Gene Hackman), all the while the picture of the line to be replaced plays over and over again behind them, just as on a looping stage of yore.

Daisy Clover presents a very dramatic and stylized looping session. It is fascinating how the session is staged, photographed, edited and mixed. The story takes place in the early 1930s, but the techniques depicted bear little relationship to how dialogue replacement was actually done at the time. What it surrenders in accuracy, however, it gains in narrative impact for the particular story it tells.

The classic musical Singin’ in the Rain contains a brief scene that turns out to be a very accurate representation of looping. The story of the film takes place during the transition from silent movies to talkies. The fictitious studio in the story is stuck with a beautiful leading actress (Jean Hagen) who has a screechy natural voice. Any illusion of grace is shattered as soon as she opens her mouth to speak. Contractually stuck with her, the studio decides to save its investment by using the voice of another, unknown actress (Debbie Reynolds) in place of the star’s.

About 89 minutes into the story, there is a brief scene where the young actress is brought onto a recording stage at the studio. On the screen in the recording stage, the actress is shown the line that she is to re-voice. The lights are dimmed. On a black screen, a white line travels across from screen left to screen right, then the image appears of the leading actress speaking the line, and we hear her harsh natural voice. The young actress indicates that she’s ready to do a take. The lights are dimmed again. The white line travels across the black screen, serving as a device to cue her to the start of the line. When the image appears, we hear the beautiful voice of the young actress speak the line in perfect sync with the image. The filmmakers are happy; the film-to-be has been saved!

Ironically, in that scene in the finished film, Reynolds is shown re-voicing Hagen, but on the finished audio track, what the audience actually hears is Hagen’s real voice coming out of Reynolds’ mouth. During post-production, the directors decided that Reynolds’ voice didn’t sound sophisticated enough, so they had Hagen re-voice herself. Her screechy voice was not her natural voice, but rather a performance voice to fit the role. Therefore, the person doing the re-voicing was actually re-voiced by the person she was supposed to be re-voicing!

In the accompanying photo from Singin’ in the Rain, note that Reynolds is resting her left hand on a steel bar. Those were called “performance bars,” and they are still present on the ADR stages on the Sony lot (formerly MGM Lot 1).

Douglas Shearer, MGM’s sound director from 1928 to 1955, told a story in a 1938 article in Behind the Screen: How Films Are Made: “Jeanette MacDonald, when she first sang for films, was inclined to sway in time to the music she was singing. That caused microphone trouble. So she was asked to stand behind a chair, holding the back of it with her hands, which restricted her instinctive movements.”

Eventually, the MGM machine shop constructed a set of stand-alone metal bars so that actors could hold onto something sturdy while singing or speaking to help keep them in place before the microphone.

– R.J. Kizer

Dub Versions

For the general public, “dubbing” in movies means replacing words, usually from the original language spoken by the on-screen actors to the language spoken by members of the audience. Some movies have very good dubbing while others do not.

To the latter point, one of the first movies I worked on was a Filipino horror film that required almost the entire dialogue track to be post-synchronized. Time and money limitations forced us to race through the process with less than satisfactory sync results. The Daily Variety review of the film ended with: “Dubbing ranks with the worst of the 1970s Italian-Yugoslavian productions.”

Paramount Pictures

In the movie business, however, dubbing has several meanings. As already mentioned, it can mean dialogue replacement from one language to another. It can also mean any dialogue replacement done in post-production (ADR); it can mean re-recording too; and it can mean making an exact copy from an original sound element. Similarly, a “dub” can mean a sound mix, the physical audio element that resulted from a mix, a specific element from a post-synchronization session, or an exact copy from an original sound element.

A character in a movie who has been “dubbed” is a character whose voice was replaced with that of another. It was commonplace in movie musicals of old to use a different voice for singing — one more trained and polished than the original actor’s. Marni Nixon (who passed away in July 2016) had a long career of providing the singing voice for such actresses as Deborah Kerr (The King and I, 1956), Natalie Wood (West Side Story, 1961), Audrey Hepburn (My Fair Lady, 1964) and many more.

All of which is prologue to the question: Where did the word dubbing originate? It’s listed in H.L. Mencken’s classic work The American Language (1938) as one of the new words added from the business world, but Mencken did not give a definition or an origin. The word has no relationship with “dub” as in to confer knighthood (“I dub thee: Sir Lancelot”). That particular meaning is believed to have come from the medieval French word adouber, which meant “to dress or equip in armor.”

In fact, the Hollywood term was adopted from the phonograph industry, where it was jargon for “doubling,” and originally meant to make a copy of the original. As reported by Kenneth F. Morgan in the 1931 Recording Sound for Motion Pictures:

“In the days of soft wax, cylindrical records, duplicates were made by a doubling process consisting of a reproducing machine connected to several recording machines by means of pipes. Later, a mechanical pantographic arrangement was developed for duplication; and finally, copies were made wholesale by means of the electroplating process, with the result that dubbing was no longer necessary.”

The second, third and fourth editions of the American Cinematographer Manual (1966, ’69 and ’73) had chapters on sound wherein the word dubbing was only used to mean the process of re-recording or making a sound mix. To this day, the words “dubbing stage” are taken to mean a re-recording stage.

Dubbing, as in voice replacement, can be traced back to an article that appeared in the July 1929 issue of Photoplay magazine. Entitled “The Truth About Voice Doubling,” it was an exposé of the then-new Hollywood practice of replacing actor’s voices with those of professional singers.

But it also dealt with an issue critical to Hollywood back in the years 1928-29 — namely the conversion of silent films to talkies. When Paramount decided to convert The Canary Murder Case (1929) to a talkie, its star, Louise Brooks, had already departed for Europe, so another actress was hired to provide the voice. From the article:

“Most of the doubling that Margaret Livingston did for Louise Brooks in The Canary Murder Case was accomplished by ‘dubbing.’ Miss Livingston took up a position before the ‘mike’ [sic] and watched the picture being run on the screen. If Miss Brooks came in a door and said, ‘Hello, everybody, how are you this evening?’ Miss Livingston watched her lips and spoke Miss Brooks’ words into the microphone.

“Thus a soundtrack was made and inserted in the film. And that operation is called ‘dubbing.’

“All synchronizations are dubbed in after the picture is finished. The production is edited and cut to exact running length, then the orchestra is assembled in the monitor room (a room usually the size of an average theatre!) and the score is played as the picture is run. The soundtrack thus obtained is ‘dubbed’ into the sound film or onto the record, depending upon which system is being used.”

While the article correctly notes that the audio recorded after the fact was incorporated into the finished film via dubbing (re-recording), it quickly became commonplace to use the term to also mean the act of voice replacement. Or, dubbing doubles into the dub.

– R.J. Kizer