by Rob Feld

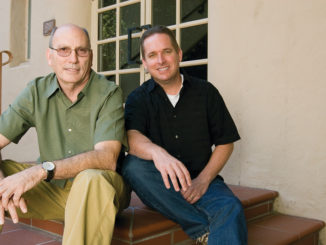

In conversation, one gets the sense that Bob Ducsay, ACE, is at core an artist who just happens to find himself in the body of a sought-after film editor.

As a child growing up in Miami, he occupied himself making 8mm movies on his own, cutting them together without knowing what editing was. In college, when he started thinking about what he wanted to do with his life, his mind turned back to movies and this thing he had heard of, film school. He was drawn to photography, theater, and lighting, but once in the Graduate Film Program at USC, he found that editing appealed to his interests in technology and, more importantly, the craft of storytelling. But when Ducsay’s classmate, director Steve Sommers, got a low-budget film right out of USC and asked him to cut it, the die was cast. Sommers was to keep Ducsay busy in the years to come with a string of films as their careers progressed through larger and more complex projects.

Currently, Ducsay has completed his fourth collaboration with director Rian Johnson, “Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery,” which has become a hit on Netflix. A follow-up to their 2019 “Knives Out,” the story again sees detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) investigate a stylized whodunit with an eclectic cast of characters loaded with motives for murder. While staying classically in genre with many interlocking clues and motivations to track, the film’s contemporary energy and humor gave Ducsay many masters to serve and no objective barometer to tell if any of it was working, save for the audience itself.

CineMontage: Getting a first feature right out of film school sounds like a mixed blessing.

Bob Ducsay: I had cut a 40-minute, 35mm master’s thesis film and I thought, A feature is only another hour. How hard could that be? It was unbelievably hard. If I knew better, I wouldn’t have done it, which would have been bad, too. The movie actually turned out pretty well and launched my career. But the suffering and getting knocked down a bunch of pegs, realizing you really don’t know anything, is extremely helpful. I was fortunate but the downside of never being an assistant is that there were a million things I didn’t know about, like dealing with a studio or producers. There’s a lot more to the job than cutting a movie and they have an impact because it is a business, and you have people that you answer to. It’s not where the focus should be, but practically speaking, you have to understand how to navigate those things. There were a lot of hard lessons along the way because I wasn’t hanging out in the cutting room, watching these things happen when I wasn’t responsible for them.

CineMontage: What was the greatest lesson you took with you?

Bob Ducsay: That it’s a lot harder than it looks. I’ve been doing this over 30 years now and I still find it endlessly difficult. I love doing it but it’s an avalanche of work and you sometimes can’t imagine getting to the end. With each success, you get a little more confidence that you’ve seen so many things that you’re probably going to be fine in the end, and with a little luck, the movie will be good. I’ll sit with dallies thinking, How is this going to come together? until I remember I’ve done this before, and I will figure it out.

CineMontage: You have deep and repeated collaborations with both Steve Sommers and Rian Johnson. Do your processes differ between them?

Bob Ducsay: They’re very different people making different kinds of films, but … the process is similar. I have a special appreciation for writer-directors, which is what both Steve and Rian are. If I didn’t know anything about how it works, I would think that writer-directors would be far more precious about the words they put on the page and the vision of their scripts. But what I found is that they are both happy to make changes in post-production because I think that they intrinsically understand the parallel between writing the screenplay and what happens in post: it’s an opportunity to magnify and refine the vision that you had in the screenplay. Typically, a couple of weeks after photography, I have a cut of the film and Rian and I go through it reel by reel. We don’t watch the whole film. We watch reel one and make changes until we get to the end. Then we put up reel two and make changes through the end of reel two and so on, until we get to the end of the film. Only once Rian’s had a chance to put an early mark on the edit do we sit down and watch the whole film. I think that works out really well because we have the opportunity to refine things and to take care of the more egregious changes—something I didn’t anticipate or something that isn’t the way that Rian envisioned it. So, when we watch the movie the first time, it’s not just my original take on putting the film together; it’s my original take plus some secret sauce, and I love that.

CineMontage: How would you characterize the footage that Johnson gives you? Does he give you a lot of options?

Bob Ducsay: I would make this general observation about every film I’ve ever worked on: the footage tells you how it should be cut because the style is inherent in how it’s been photographed. The movie does in fact speak to you. Rian is going to be precise in how it is prepped and photographed and how we ultimately put it together. But there’s the script, there’s the thing that was photographed, and there’s the edit. All three things are different. Sometimes the difference between the script and the finished movie is not so great but sometimes it’s enormous, and I think that certainly varies between the movie and the director.

CineMontage: There’s so much for an audience to track in a whodunit like “Glass Onion.” Is how to do it all clear from the footage?

Bob Ducsay: In movies like “Knives Out” or “Glass Onion,” which have structural intricacies, a lot of that has to be in the screenplay because the storytelling depends on that stuff working. Rian is a great screenwriter. Both “Knives Out” and “Glass Onion” are perfect Swiss watches of screenplays. They’re very precise because they have to be. When you get into post, some things don’t work and some things need to be adjusted; what you show and what you don’t show. “Glass Onion” is a perfect example of that. We pushed as far as we could to be completely honest with the audience. If you were to watch the movie again with the knowledge that you have of the outcome of the film, you would see many things that are just there in plain sight. That was one of the great delights of cutting the movie. As an editor, as a director, you have to reframe your point of view to that of the audience, which is hard to do because you know everything that’s going to happen, you know all of the mechanics. So, we tried hard to push, knowing what we knew about where an audience is looking, what an audience is thinking about, what they think is important at a particular moment. There’s a sleight of hand. There are a lot of little details that are pushed to the max. It amazes me, some of the things that we were able to get away with that an audience watching for the first time doesn’t realize that if it paid attention to that moment, it would know a lot about the outcome of the film. Based on the previews we did, I think we succeeded pretty well in guessing what would work and what wouldn’t. But with experience, I think you do get better at knowing what the audience is paying attention to and how they understand things. They always surprise you though, which is the reason we do screenings and preview. You can realize they’re way ahead of you or that they’re not getting something that seems obvious. So, you do make mistakes, but over time you do begin to have the ability to put yourself in their shoes and guess reasonably well.

CineMontage: There’s nothing like real people.

Bob Ducsay: Preview screenings are essential. Your in-house screenings with other filmmakers are useful because they speak the same language. They can have notes that are both precise and helpful. But filmmakers are not a normal audience. A real audience has no agenda. They don’t start with their arms crossed, hoping your movie’s not better than theirs. They’re just going to see a movie and they want it to be great. You might not like what they tell you, but you can’t dismiss it or argue with it because it’s a pure point of view.

CineMontage: The cut has a great deal of power in such an intricate story.

Bob Ducsay: I’ll tell you one thing that’s extremely meaningful to me. Rian is a great believer in simplicity. On some movies you’ll insert a cut for energy. It isn’t really necessary but you do it because stylistically, over the history of cinema, things have become more cutty. I don’t think that there’s anything specifically wrong with that—I’ve seen plenty of movies that are aggressive editorially that I admire very much. However, I think the notion of simplicity being a goal for all aspects of filmmaking, particularly in the editing, is an admirable one and one that I believed in before I worked with Rian. But in working with Rian, I feel I’ve been able to apply and understand it much more; the notion of, if you’re not gaining anything significant with a cut, stick with where you’re at. It’s often hard to do because there’s a hierarchy of why you choose to cut—simplicity can’t be the only thing. But if you put a little bit of extra pressure on yourself to say, Are you sure this is necessary? I personally find it helpful because know you have a good reason for doing it every single time, and you’re not just inserting edits for style. You are serving a higher cause.

CineMontage: I know you didn’t cut “Brick” with Johnson but there’s a chase scene in there that makes such creative use of editing and sound design, that the production value of a low budget indie is noticeably elevated. He’s a filmmaker that appreciates what each element has to contribute to the greater whole.

Bob Ducsay: That’s absolutely correct. And this is what you hope for with every filmmaker you work with; the appreciation of the power of post-production, the power of editorial. But it also applies to all the other areas of making the movie because it’s all intertwined—the framing, the coverage eventually inform the edit. I think one of the things that I most appreciate about working with Rian is his deep understanding of what every department is capable of, including my own.