by Peter Tonguette

Photo by Marcus Taylor.

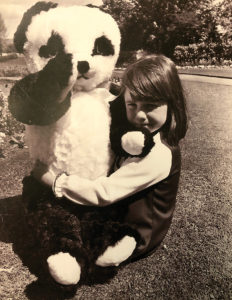

As a youth in Dublin, Ireland, Clare Knight (née De Chenu), ACE, had a decidedly artistic bent. The daughter of a stage actor-turned-architect and a schoolteacher, she dreamt of becoming an artist. She won numerous art competitions, including the world-famous Texaco Children’s Art Competition. For her prize, the child was given her pick: Would it be money or a life-size toy panda?

“I chose the panda because the Irish Zoo had no panda,” Knight relates. “In Ireland, we didn’t have pandas, or even see pandas, so they were very unusual. And my father said to me, ‘When you didn’t choose the money, I knew you were going to go into something creative.’”

Her dad was on to something: Upon graduation from Saint Martin’s School of Art in London, where she studied film, Knight entered the British motion picture industry, first working on live-action projects before turning to animation post-production. As an animation editor in Hollywood, she has worked on several of the best-remembered animated features of the past 15 years, including Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron (2002) and Madagascar (2005).

And just as significantly, Knight’s youthful enthusiasm for pandas anticipated one of her career milestones: her solo editing of the three-film Kung Fu Panda series (2008, 2011, 2016), produced by DreamWorks Animation and released by Paramount Pictures. In the China-set, talking-animal trilogy, Jack Black lent his verbal talents to a kung fu-besotted panda named Po. Dustin Hoffman voiced Po’s mentor Master Shifu, a red panda, and the voice cast also included Angelina Jolie (Master Tigress) and Lucy Liu (Master Viper).

Not lost on the editor is the link between her prize as a child and the acclaim she won as an adult for her panda-centric films. “Cut forward from this Irish girl from Dublin coming all the way over to work at DreamWorks,” Knight reflects. “A lot of things happened for me that connected me back to Ireland, back to my family, back to things that my family was very surprised that I managed to achieve.”

Initially a student at the Wimbledon School of Art in London, Knight studied theatre design but was encouraged to shift gears to film by a teacher who, upon surveying the student’s canvases, noted their cinematic scale. “My teacher said to me, ‘You know, these look like screens — have you thought about film?’” she recalls. “I think they were tired of me spending so much on materials as well.” Having moved onto Saint Martin’s, Knight harbored dreams of directing, but she ultimately specialized in editing. “I was very fascinated with David Lean, and I knew that he had come from being an editor to being a director,” she says.

Following Saint Martin’s, she worked on documentaries at Channel 4 and the BBC, breaking into features as a second assistant editor on Neil Jordan’s We’re No Angels (1989). Her transition to animation editing came after she encountered a classified ad soliciting applications for an unusual-sounding job. “They were looking for someone with ‘cartoon room experience,’” Knight remembers. “I was like, ‘Cartoon room? I don’t even know what that means.’ I found out that I was the only person who replied because it had been a misspelling. It should have been ‘cutting room experience.’”

Knight won a position in the editing room of the Steven Spielberg-led British animation studio Amblimation, where her projects included An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991) and We’re Back! A Dinosaur’s Story (1993). The young assistant editor enjoyed the esprit de corps of the studio. “It was an open-plan space, so editorial was right beside the directors,” she comments. “I really felt a part of it all.”

In the mid-1990s, Amblimation was incorporated into DreamWorks, which Spielberg formed in partnership with Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen. The new studio went to work to create The Prince of Egypt (1998), on which Knight served as first assistant editor. “When DreamWorks was started, Jeffrey Katzenberg came over and played us all ‘Deliver Us’ from The Prince of Egypt, the Hans Zimmer song,” she explains. “We all signed contracts and came over. They needed to have an experienced crew together really fast. It was very scary to me, because I’d never been to America.”

During her time at DreamWorks, she developed a reputation as an editor who could elicit emotion in a project. “Women were thought of kind of like, ‘Yeah, they’ll be able to find the heart in editing, but we don’t know if they can do comedy,’” comments Knight, who was eager to prove her ability to edit more than just dramatic scenes. Her opportunity came with Madagascar, on which she worked initially as an additional editor before being asked to lead the project when the original editor left to work on another film.

“The studio was having trouble on the movie, and I was given two weeks to get it in shape,” says Knight, whose contributions included pinning down the heretofore-elusive tone of the movie, on which she shared credit with Mark A. Hester and H. Lee Peterson, ACE. “We couldn’t figure out if the characters were going to be scary beasts or what,” she explains. “Someone came up with the idea, ‘Well, what if they’re just party people?’ So, at the last moment, I thought, ‘Oh, I remember a song,’ and I brought that to them. I set up a scene using the beat of Reel 2 Real’s ‘I Like to Move It.’ The minute I saw Jeffrey Katzenberg’s foot tapping, I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m in — I’m all right.’”

After pulling together Madagascar at the 11th hour, Knight was given the opportunity to guide a film from start to finish. “They had confidence then to offer me Kung Fu Panda,” she says. The project began as a “very, very minor treatment” that evolved into a pitch, at which time the story team, led by Jennifer Yuh Nelson, became involved. “We would start with Act 1: ‘How do we want to open this movie?’” the editor explains.

As the film advanced through the development process, screenwriters Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger were brought in; meanwhile, Knight assembled sketches of scenes. “We would use temp voices from the studio, temp sound effects, temp music,” she says. “We were doing this on Avid. We could change it over and over again, but we were trying to figure out what the story and the character arc were.” At six-week intervals, her edited scenes were screened for studio executives.

Eventually, Kung Fu Panda was authorized to go into production, although a hiatus was taken while rewrites were completed. “When I came back, they had actually written a script, and we started for real,” Knight remembers. “We sent our first scene into production: Po and Shifu in their first meeting. We had already recorded Jack and Dustin.” Storyboarded scenes were cut together by the editor, who worked in collaboration with directors John Stevenson and Mark Osborne. “We demarcated what the scenes were,” she adds. “I might have a close-up, then it goes to a mid-shot, then it goes to a wide shot.”

During the layout process — which Knight describes as consisting of “just essential blocking of forms” — emotion can be lost, but it can be rekindled during the animation stage. “We can adjust the camera because we might say, ‘Oh, no; we need a single on that. We can’t have that be a two-shot because the emotion of the scene is lost,’” says the editor, who also is carefully attuned to timing. “Sometimes, we’ll look at a joke and say, ‘Why is this not working?’ And it can be as simple as because it’s a few frames off or it needs to be shifted just slightly.”

Knight says that she became a “full-rounded editor” on the project. After proving that she had a gift for comedy on Madagascar, the editor expanded her repertoire to include action on Kung Fu Panda. “The scene where Tai Lung [Ian McShane] breaks out of the prison is one of those things that I feel goes from one level to the next,” she observes. “It took a lot of work to get it to be more surprising as it evolved. It was of that time when, particularly in animation, they thought that action could only be done by a man.”

But she did not discard her talent for editing emotional scenes. “I brought to it my own feelings of loss as a child,” acknowledges Knight, whose mother died when she was young. “One of the most moving pieces is Oogway [Randall Duk Kim] leaving. I really felt that here was something I could show to other children about loss, with which they will connect, but not make them feel the complete and utter devastation.”

Kung Fu Panda was previewed three times, with sequences — and sometimes specific jokes — adjusted throughout. In one scene, a joke about Mantis (Seth Rogen) performing acts of acupuncture was received so well that the scene that followed had to be adjusted. “I had to lengthen the next scene so much because of the laugh,” Knight recalls. “Over the three previews, we kept changing the timing of that because we’d lose the next piece of dialogue.”

When released in June 2008, the film was popular with audiences, grossing upwards of $215 million in the US. For Knight, more important than the box office receipts were the personal and professional relationships she forged on the film. When Nelson was chosen to direct Kung Fu Panda 2 and 3, Knight joined her. “I loved her sense of story,” the editor attests.

And, in the midst of making the original Kung Fu Panda, the then-Miss De Chenu met her future husband, former Seinfeld actor Wayne Knight. “Somewhere halfway through the movie, I got married,” Knight says. “The producer suggested, ‘Why doesn’t he do a voice?’ Wayne did a cameo at the beginning of the movie, so that was very nice.” Their son, Liam, contributed the voice of Baby Po in the first sequel. “When we were looking for baby sounds, I noticed all the sound effects were about 50 years old,” she comments. “So, I came home with a recorder and recorded Liam. It gave character to Baby Po.”

The Kung Fu Panda series was a boon to Knight, who in June was invited to join the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). “Joining AMPAS is very meaningful to me,” the editor reflects. “When I first came to Los Angeles, I secured a position as a seat-filler at the Oscars to feel ‘part of it,’ if only vicariously. Now, as a newly minted Academy member, I am not an interloper or pretender but a peer.”

And upon traveling to China for the release of Kung Fu Panda 2, Knight finally met a panda — not a toy or an animated panda, but a real one. “I love pandas,” she says. “It was really, really special — but I was shocked at their claws.”