by A.J. Catoline • portraits by Wm. Stetz

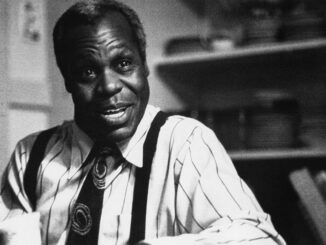

When the winning editor was announced for Outstanding Single-Camera Picture Editing for a Comedy Series at the 2016 Emmy Awards ceremony, picture editor Kabir Akhtar, ACE, was stunned to hear his name. “When you get up on that stage, you forget any speech you may have wanted to give. You are out of your head,” says Akhtar.

Having won for cutting the pilot episode of The CW’s Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Akhtar was surely conscious — even as he remembers “dancing to the show’s theme song the whole way down the aisle to the stage” — that he had also made Emmy history.

“I am the first person of color to win an Emmy in this category,” the Indian-American picture editor acknowledges. “It has been a category for 14 years, and to be the first one is very exciting. It’s incredible to be honored by your peers, out of all the thousands of television episodes made. It blows my mind every day.”

Through life and career, Akhtar tells CineMontage, he has certainly encountered some questions about his ethnicity. “It’s always subtle, super soft,” he says, “but it’s there.” Akhtar recalls people asking over the years if his parents approved of him dating someone white. “They wanted to know if there were any cultural issues,” an incredulous Akhtar reveals. “And I would say, ‘I’m from Philadelphia. I’m an Eagles fan!’ Why are they asking that?”

“I don’t think people are intentionally insensitive, it’s just that they haven’t thought much about what they are saying.”

Diversity has become an issue front and center in today’s political zeitgeist of Hollywood. Two years ago and last year, there was the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite. This year, Oscar fared much better with nominations — and some wins — for people of color, but still infamously fumbled the announcement of the winning African-American filmmakers for the Best Picture Moonlight.

The Editors Guild has formed a Diversity Committee to study the issue of diversity in the post-production industry. A survey was recently sent to members to inquire what experiences they may have to share in which race, gender or sexual orientation may have been a factor on the job.

On that note, Akhtar remembers an incident when he was editing a TV show for comedian and producer Tracey Ullman. She planned to shoot a new series on location in Mumbai, India. It was logical for Akhtar, who has a hyphenated career as a director-editor, to ask if he could be hired to helm episodes in the country of his heritage. Ullman agreed, and this would be a proud moment for Akhtar to be a director in the land of Bollywood. He would follow in the footsteps of his uncle, Javed Akhtar, who is an Indian screenwriter and cultural poet, and his cousin Farhan, who is a feature director and star there.

“In India, it [being Farhan’s relative] is like being Barack Obama’s brother — it helps keep me humble,” Akhtar offers. After the Emmy ceremony, The Times of India recognized the family dynasty with a headline: “It’s a Win for the Other Akhtar!”

When Akhtar returned to London to post the show, he encountered a local director there. “She was a young lady who fancied herself way more worldly than she actually was,” he recalls, “and she asked me what my favorite part of the shoot in Mumbai had been. I said, ‘Well I loved the whole thing, but I especially enjoyed working with my cast.’ She replied, ‘Of course, and which caste are you?’”

Akhtar says he loves a good diversity joke. He remembers when Chris Rock, as host of the 2016 Academy Awards telecast, critiqued Hollywood for disguising its diversity problem with soft bigotry by being “sorority racist.” Rock imagined an executive saying, “It’s like, we like you, Rhonda. But you’re not a Kappa.”

“I stood up and applauded when I heard that,” Akhtar remembers. “I don’t think people are intentionally insensitive, it’s just that they haven’t thought much about what they are saying.”

Akhtar is a member of the Editors Guild, American Cinema Editors and the Directors Guild, where he recently participated in a panel discussion about diversity hiring in film and television. “I am pleased there has been a real push to discuss diversity and to try to have more inclusiveness in the industry,” he says. “It’s hard to know what we can do about it, but in order to make progress, we need to learn what the issues are.

“I haven’t ever had a problem getting hired to edit because I was brown,” he continues. “But I look around and don’t see a lot of diversity in post. I don’t know if there are a lot of people not getting opportunities, but we need to hear from our members to find out. If there is a problem, why?”

The editor’s accolades for best comedy editing are well deserved, because he cut the Crazy Ex-Girlfriend pilot episode twice. The original pilot was commissioned as a half hour for Showtime, which eventually passed on the project. Six months later, The CW picked up the show for a series, but wanted the episode extended and reformatted to an hour’s length. This task landed squarely on Akhtar, who dove into the challenge to double the cut’s time. The producers had only shot three additional scenes. “We were lucky enough to put back in every moment we had taken out to get to time in the original half-hour show,” he explains. “We had to make it work in a new way.” The journey from snatching the pilot show from the jaws of one studio’s pass bin to making it into a Golden Globe Award nominee and winner for another company is a rare yet wonderful example of an editor transcending his or her role and place in the cutting room and becoming a principal creative collaborator.

Photo by Wm. Stetz

When Rachel Bloom won the 2016 Golden Globe for Best Actress in a TV Series (Comedy or Musical) for her starring role as the show’s namesake “crazy ex-girlfriend,” she went to work the next day and celebrated with her editor, posing for a photo with both of them jointly holding the trophy.

Bloom is also an executive producer and co-creator, and when the show was picked up for a second season, Akhtar was invited to direct an episode. The producers obviously recognized his work not only as editor, but as one of the show’s founding fathers. Comedy traditionally works in the half-hour format, so to extend the show longer required an editorial feat of collaboration with the show’s writers. For Akhtar, this unique experience reinforced the theory that the craft of editing is similar to writing with picture and sound. Although he cautioned that the journey was fraught with the potential shoals of executive writer egos upon which any editor could run aground.

“People often don’t understand what we do as editors, but what we are doing is the final rewrite of the show,” Akhtar explains. “We speak ‘editor language,’ but oftentimes editors don’t speak ‘writer language,’ and it’s so important that we do. It is the editor’s job to protect the show from bad acting, bad directing — and even our own mistakes in post. Editors who are successful are able to speak to writer-producers in their language and collaborate in shaping the comedy and story.”

Akhtar advises that an editor can earn trust by showing respect for all the creative work that has come prior to the first day of shooting when he or she begins on a show. “I think we put ourselves in a better position if we understand the deeper story,” he says. “How did the show get to this point? What is the story of the writers and producers who have worked so long and hard to make this show happen?”

A new layout for the cutting room: “It creates a spirit of partnership. You watch the cut together instead of driving the Avid like a chauffeur.”

The Emmy winner developed an effective strategy for improving an environment that fosters collaboration. When the director and writer are in the room during the editorial process, Akhtar suggests, “Everyone is like a pro racecar driver, and all of us want to drive the car. Nobody likes to sit in the back seat.”

The CW Network

The layout of most cutting rooms are ineffective, he feels, because the editor typically sits facing the console, while the producer or director sit behind. “It’s dehumanizing for them to be watching your back all day as you work,” he says. “So I re-arranged my cutting room.” He moved the Avid desk to be perpendicular to the couch so he could face the producers where they sit, all while keeping the monitor they watch facing forward. This way he can watch them as they watch the monitor.

This new layout has so many advantages, Akhtar claims. “You can see the directors’ and producers’ faces as they watch the cut. If they like or don’t like something, you can see it on their faces, how they react. You’re no longer listening to their notes from behind, over your shoulder, but you are now having a collaborative conversation, face to face. It creates a spirit of partnership. You watch the cut together instead of driving the Avid like a chauffeur.”

Akhtar began his career editing reality television, where the improvised workflow “taught me how to manage egos,” he says. He then went on to cutting scripted episodic television. “Scripted and unscripted may be different skill sets, but they are overlapping,” he adds. “The editor is still rearranging story points on the timeline.

“Editors should constantly be reinventing their careers,” continues Akhtar. “Let’s not be like that old industry joke: ‘How many editors does it take to change a lightbulb? None. It’s fine the way it is.’ The challenge is to keep trying to make a cut better, keep trying to make a scene better, keep trying to make a show better.”

The editor also recommends a vertically adjustable edit desk. “Standing while editing is key, dancing while cutting music is key; editing is musical,” he says. Akhtar has certainly been dancing on air since he won his Emmy. “But don’t expect to see me in a Bollywood musical anytime soon.”

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend returns for its third season later this year.