by Peter Tonguette

The year was 1976. The place was the New York brownstone of editor Ralph Rosenblum, ACE. And the film was Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, released the following year to wide acclaim and four Oscar wins. One day after work, Allen and Susan E. Morse, ACE — later his main editor, then an assistant editor — found themselves leaving the cutting room at about the same time.

“He had his car, which was then a cream-colored Rolls-Royce, and he said, ‘Would you like a lift?’” Morse recalls. “I said, ‘Well, I’m probably not going in the same direction as you are.’ He said, ‘It doesn’t matter. Just drop me off, and my chauffeur can take you the rest of the way.’”

As they were driven through the streets of New York, Allen expressed his concerns about Annie Hall, but Morse tried to reassure him about where the film was headed. “He seemed interested in continuing the conversation about what he and Ralph had been discussing: the problem of how to end the film,” Morse recounts. “And, in my innocence as a 24-year-old, I said, ‘I’m a woman and I can tell you that I identify with the Annie character and I think a lot of women my age will. I think you have to trust that element. You don’t need another big laugh.’”

United Artists/Photofest

In the years that followed, Allen would often look to Morse for cutting room solutions; two years after Annie Hall, she began her 20-year tenure as Allen’s editor on a string of his most successful films, including Manhattan (1979), Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989).

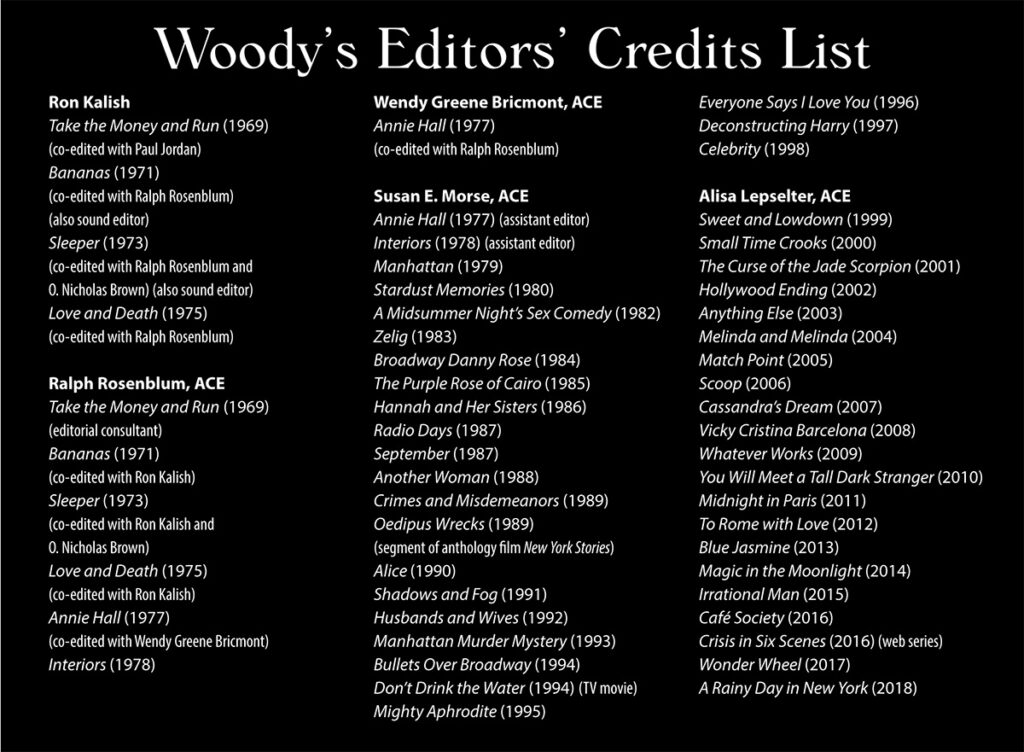

Although Allen’s work can be divided into genres, ranging from slapstick farces and romantic comedies to dark dramas and the occasional murder mystery, the easiest way to classify his career is to look at who receives the credit of film editor. For nearly a half-century, the director has worked with only three picture editors, with a few exceptions.

From 1969 to 1978, Allen worked almost exclusively with Rosenblum (1925-1995), who was hired on his debut film, 1969’s Take the Money and Run (Allen disavows 1966’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, a re-dubbed Japanese spy movie, on which he is credited as director), and went on to cut classics, including Annie Hall. In 1979, Morse replaced Rosenblum, remaining in the position until 1998. And, at the end of the century, Allen changed editors again, hiring Alisa Lepselter, ACE (see accompanying story, page 72), to cut Sweet and Lowdown (1999) and all of his subsequent efforts to date.

CineMontage spoke with editors representing each era: Ron Kalish, who worked as an editor with Rosenblum, Wendy Greene Bricmont, ACE, who shared an editing credit with Rosenblum on Annie Hall, Morse and Lepselter. Their memories paint a portrait of a director whose creativity did not stop on the set but continued in the cutting room.

United Artists/Photofest

United Artists

After garnering attention as a stand-up comic and writer, Allen kicked off his directorial career with a series of raucous, often liberally structured comedies. Yet Kalish, who collaborated with Rosenblum on four Allen films, remembers the director as a subdued presence in the cutting room. “Everybody would say to me, ‘Oh, it must be a blast working with Woody, because it must be joke after joke all day long,’” Kalish says. “It was totally the opposite. If something didn’t work, he would stare at the wall and say, ‘Why doesn’t it work?’”

If the filmmaker was in a serious state of mind, perhaps it was because Take the Money and Run had a famously fraught post-production. The film, which adopts the format of a faux documentary to recount the criminal doings of bank robber Virgil Starkwell (Allen), was judged insufficiently uproarious when assembled by original editor James T. Heckert (1926-2008).

“I kept cutting the film down, shorter and shorter; throwing things away, throwing things away,” Allen recounted in the 1994 book Woody Allen on Woody Allen. “Finally I had no film. So the production manager of the film said, ‘Let’s bring in Ralph Rosenblum, who is a very renowned editor, very gifted.’”

The New York-based Rosenblum accepted the assignment, earning the credit of editorial consultant. In his 1979 memoir, When the Shooting Stops…the Cutting Begins, Rosenblum conceded that Heckert was “a competent West Coast veteran,” but wrote that the film was “too short, with too few jokes, and with enough dead spots to convince an untrained viewer that the entire work was rather flat or mediocre, if not a total dud.”

Kalish, who shared an editing credit on the final film with Paul Jordan, recalls that the original editor had dropped wholly edited scenes that were often very funny. “For some odd reason, the editor in California didn’t really know how to use them,” Kalish says. “We just took everything apart, reset all the dailies, reviewed them and started from scratch.”

“Since the film was haphazardly plotted, it didn’t matter too much where one scene or another ended up,” Rosenblum wrote in his book. “I was able to move things around at will to serve the rhythm and the pace.” By the time their work was complete, Kalish remembers, the film ran about 75 minutes. “[The producers] said, ‘No, Woody, we need at least an 80-minute film,’” he recounts. Rosenblum, who had already rejected several proposed endings as “sentimental, weakly amusing or sad,” asked for a fresh finish — including the famous scene of the now-imprisoned Starkwell molding a bar of soap into a firearm — and boosted the running time to 85 minutes.

Cinerama Releasing Corporation/Photofest

United Artists/Photofest

Rosenblum and Kalish continued their collaboration with Allen on Bananas (1971), which represented an advance in ambition for the director. “To me, Take the Money and Run was visual comedy — perfect Woody Allen-type stuff,” Kalish comments. “Bananas was also visual comedy, but it was more structured. It leaned more on the script rather than having to use our imagination: ‘How do we put this together?’” Even so, Rosenblum wrote that the film required careful pruning in post-production: “Because Woody’s comedies are based on a continuous stream of jokes and skits, a larger than usual portion of our editing work entails a search for the moments that work, and a careful weeding out of the ones that do not.”

A scheduling conflict prevented Rosenblum from cutting Allen’s next film, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask (1972) — edited by Eric Albertson, ACE (1937-2009), with Heckert serving as supervising film editor — but he rejoined the director for Sleeper (1973), a sci-fi comedy in which Allen appears as an emigre from 1970s Greenwich Village adjusting to the 22nd century. “Technically, Sleeper was more creative,” says Kalish, who returned to work on the film (sharing credit with Rosenblum and O. Nicholas Brown). “It wasn’t just joke, joke, with two people.”

More ambitious still was Love and Death (1975), which manages to spoof Russia at the time of the czars, the fiction of Leo Tolstoy and the cinema of Ingmar Bergman. “Once we got to Love and Death, I looked at Woody and said, ‘You’re going to lose a lot of your fans,’” Kalish recalls. “He said ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Because they like your visual humor, and now you’ve gone into more sophisticated humor.’ He said, ‘Well, that’s where I’m going.’ It was a much bigger picture compared to the previous, which were more controlled.”

Even as Allen’s films grew grander, however, Kalish did not detect major differences in his attitude about editing. “Woody still relied on Ralph’s and my input, and we would put it together with him sitting there,” he says. Pointing out that the director was present in the cutting room as time permitted, Kalish adds, “He was always writing the next script — even while we were cutting — so he wasn’t there all the time. It was a matter of, ‘Woody, I have 20 minutes to cut. Why don’t you come in?’” Kalish also worked as an uncredited sound editor on Bananas and Sleeper.

Take the Money and Run remains Kalish’s favorite Allen film, troubled post-production notwithstanding. “I saw Woody growing and getting better and better, but it’s almost like a first-born. You sort of like your first-born better than the next one.”

Kalish’s collaboration with Allen came to a close after Love and Death, but Rosenblum stayed on to help shape what became one of the director’s signature achievements: Annie Hall, which was released as a romantic comedy centered on writer Alvy Singer’s (Allen) relationship with his sometimes girlfriend, Annie Hall (Diane Keaton). But it was originally intended as a patchwork portrait of Singer’s romantic life and mental state, with enlarged roles for such ultimately supporting players as Shelley Duvall and Carol Kane.

“It was about all these multiple relationships that Alvy was having and his inability to sustain any of them after a certain point,” says Bricmont, an assistant editor (along with Morse) who was promoted to editor during post-production. “It was an embarrassment of riches.” Wrote Rosenblum: “The movie was like a visual monologue, a more sophisticated and more philosophical version of Take the Money and Run.”

Yet it was the core relationship between Alvy and Annie that stood out. “When we first screened the film in script order, it was pretty chaotic,” recalls Morse, who was working with Allen for the first time. “It felt like a bunch of random scenes strung together until Diane came on screen. Then suddenly things began to click. It became apparent that the beginning had to be changed in order to get to her as succinctly as possible — and that the film was ultimately about Alvy’s relationship with her, not his mid-life crisis, as the opening monologue suggests.”

Thus began the process of tightening the film to emphasize that relationship and excise extraneous scenes. “It was through the sheer talent of Woody, and the collaboration with Ralph, that we finally found the heartbeat of the movie, but you had to be willing to listen to find it,” Bricmont comments. “The film was written, but it was so created in post-production. I went forward in my career with the misapprehension that all movies could and would have this kind of elasticity.”

Dissatisfied with the film’s ending, Rosenblum proposed that Allen write a voiceover to be accompanied by a montage of highlights from Alvy and Annie’s time together. While hearing Rosenblum and Allen discussing the potential sequence, Morse began pulling trims that might provide appropriate material. “Ralph turned to me and said, ‘We’re thinking about…,’ and I said, ‘Yes, I was listening to what you were saying, and these are the clips that occurred to me,’” Morse recounts. “I was just paying attention and trying to anticipate what they would want so they wouldn’t have to break stride.”

Bricmont credits the ending, in part, with the film’s reception; Annie’s Oscar haul included Best Picture, Director, Actress and Original Screenplay, while Rosenblum and Bricmont received a BAFTA Award for Best Film Editing. “The ending gave it a gravitas that allowed it to earn some respect,” Bricmont reflects. “If it had concluded with a Bananas-kind of silly ending, it wouldn’t have done the movie justice. It took a while to get there.”

When the film was finished, Bricmont relocated to Los Angeles, while Rosenblum edited one last film for Allen — the uber-serious Interiors (1978). The story concerns a trio of grown sisters (Keaton, Mary Beth Hurt, Kristin Griffith) whose lives are torn asunder by the surprise separation of their parents, played by E.G. Marshall and Geraldine Page.

Morse is credited as an assistant editor, but her contributions to the film’s editing increased at the suggestion of Rosenblum, who was uncertain about Allen’s dramatic turn. “Ralph had been very dispirited when he read the script because it was not another comedy; it was so far afield from what Woody had done before,” she remembers. Allen sat with Morse, rather than Rosenblum, in the editing room — not because they had yet developed a great cutting-room chemistry, but because Rosenblum worked on a Moviola and Morse on a Steenbeck with a larger viewing screen. Her contributions impacted the released film.

In its original state, Interiors opened with a series of scenes depicting the lives of the story’s three sisters, but the material failed to establish that they were even related to each other. “There was nothing that held it together, so you didn’t know what you were watching for the first 20 minutes or so,” says Morse, who suggested to Rosenblum that they might use in the opening a scene that had played about two-thirds into the film — a monologue Marshall’s character delivered while turned away from the camera and looking at the New York City skyline — to establish that the three women were sisters and that their mother created a home environment that he characterizes as “an ice palace.”

Rosenblum proposed the idea to Allen, who brought it up at a subsequent lunch with the editing team (also including assistant editor Sonya Polonsky). Over lunch, Morse says, Allen asked to hear her perspective because he was reluctant to change the opening as planned. Morse responded with the same points she had outlined to Rosenblum. Still unsure, Allen agreed to return to the cutting room to try the idea — and they never turned back from the new opening.

By the time of Allen’s next project, Manhattan, there was no need for Morse to relay her ideas through an intermediary. After Rosenblum departed to focus on directing, the director hired her to edit the film. Morse’s contributions included shaping one of the most instantly identifiable scenes in his filmography: the opening montage in which the lead character, a writer named Isaac (Allen), reads rejected passages from his novel-in-progress over gorgeous, Gordon Willis, ASC-photographed shots showing off the New York borough of the title. Yet the montage did not originally feature a voiceover, and the soundtrack choice — George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” — was far from final.

“Woody had been vacillating between Cole Porter’s and George Gershwin’s music for the score, but when I saw the skylines that Gordy had shot, it just struck me that ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ had to be the opening cue,” says Morse. She also pulled dialogue from a deleted scene, in which Isaac talked about his work-in-progress novel, to demonstrate how voiceover would work in the scene.

“His synopsis of the novel ends roughly like this: ‘You see, to me life is like a concentration camp — full of sorrow and misery and horrific pain. And there’s no way of getting out except dying…and that’s just Chapter 1,’” Morse recalls. “I laid the entire piece down as voiceover on the beginning part of the montage — the daylight portion — so that the ‘Chapter 1’ punchline ended immediately before the crescendo that hits on the cut to the night footage. It took the burden off what had been four minutes of people having no idea what they were watching, and it had what Woody liked to call ‘the added bonus’ of letting us know that his character was a writer, which struck me as important and was otherwise not established for quite a while.”

Morse continues: “For me, it also finally made the opening montage feel like part of the film, as well as orienting the audience as to what to expect: a comedy that is also a visual and musical love letter to the city.” Ultimately, Allen wrote and recorded a new voiceover for the scene, using the “Chapter 1” motif.

Morse continues: “For me, it also finally made the opening montage feel like part of the film, as well as orienting the audience as to what to expect: a comedy that is also a visual and musical love letter to the city.” Ultimately, Allen wrote and recorded a new voiceover for the scene, using the “Chapter 1” motif.

During his years with Morse, Allen arguably enjoyed his most fruitful years as a filmmaker. He went back to the dramatic well with September (1987) and Another Woman (1988), while he perfected the art of folding two stories into a single film with Hannah and Her Sisters and Crimes and Misdemeanors. Some films, like The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), are marked by fluid, seemingly effortless editing, while others, like Husbands and Wives (1992) and Deconstructing Harry (1997), feature jagged, visible cutting.

“Husbands and Wives was amazingly close to the way Woody originally planned it,” she remembers. “That doesn’t mean it didn’t change in the editing process, simply that it changed in ways Woody had wanted it to change. The plan was to treat the dailies like documentary footage, where you could jump-cut wherever you wanted — wherever the emotional logic took you.”

Morse eventually served as editor of 22 Allen films, with her responsibilities growing to encompass overseeing subtitles and home video transfers, as well as researching video editing equipment for Zelig (1983) and model submarines for Radio Days (1987).

Only once did their collaboration come close to being interrupted. In 1987, during production of Another Woman, Morse was pregnant with her son, Dwight. “When I told Woody that I was pregnant, and therefore I probably wouldn’t be able to do the next picture, he said, ‘Wait a second. That’s too radical. We can work this out.’” The filmmaker’s solution: The screening room could be turned into a part-time nursery for Dwight. “Of course,” she adds, “I didn’t realize it would lead to my working until 10:00 p.m. the night before I went into labor!”

Along with many of Allen’s tried-and-true collaborators, Morse’s working relationship with Allen concluded in the late 1990s, due to what a 1998 New York Times article characterized as “cost-cutting measures” on his films. “A number of people who worked for years at certain prices couldn’t afford to stay on,” Allen admitted in the article. Morse agrees: “That was a matter of the studios deciding they didn’t want to back his pictures anymore, and the independent backers who took over thinking younger people would cost less.” Her last film with the director was Celebrity (1998).

Allen was faced with finding a new editor for the first time since the late 1970s. This time, instead of promoting an assistant from within the ranks, he turned to an established editor — albeit one with only a single solo feature film under her belt: After working as an assistant on several notable films, including Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993), Lepselter had cut Nicole Holofcener’s Walking and Talking (1996) herself.

“I got a call that he wanted to meet me because he was interviewing potential editors,” Allen’s current editor remembers. “Honestly, I thought it must be a mistake, but I thought, ‘Well, if nothing else, I’ll get to meet Woody Allen.’” Instead of a memorable anecdote, however, Lepselter walked away with a job to edit Sweet and Lowdown. “When I was told that he wanted to hire me, I obviously felt like I couldn’t say no,” she says. “I was stunned and thrilled — and I’ve been there ever since.”

Although his TV movie Don’t Drink the Water (1994) had been edited using the Lightworks system, Lepselter had been informed that Allen preferred to cut on film. “I would’ve happily edited on film if that’s really what he wanted, but this was 1998, and it didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me,” Lepselter observes. “I just mentioned it to him: ‘I know that people say you like to work on film, but I think you’d really enjoy working on the Avid.’” After explaining the value of using the digital editing system, Lepselter persuaded Allen to try the technology. “What I learned was that a lot of people assume he’s set in his ways, but he actually can be quite flexible.”

For her part, Lepselter was enthusiastic about Sweet and Lowdown, a serio-comic study of musician Emmet Ray (Sean Penn), whose talent with the jazz guitar does not disguise his personal faults. “It’s one of my favorite films of all the ones I’ve worked on,” she comments. “I remember when I was given the script, I thought it was the most extraordinary screenplay I had ever read; it was so funny and also so moving.”

Sony Pictures Classics/Photofest

DreamWorks/Photofest

Yet Lepselter’s years with Allen have been marked by experimentation. The three films that followed Sweet and Lowdown were unabashed comedies: Small Time Crooks (2000), The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (2001) and Hollywood Ending (2002). Then, in 2004, Allen decamped from New York to Europe, making a series of films in England (2005’s Match Point, 2006’s Scoop, 2007’s Cassandra’s Dream), Spain (2008’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona), France (2011’s Midnight in Paris) and Italy (2012’s To Rome with Love).

“It was really refreshing,” Lepselter says of Allen’s European period. “I thought that it was liberating to have people who were speaking in such a different way than the usual Woody Allen-influenced inflection.” While Allen was globetrotting, however, Lepselter remained in New York, where he joined her for post-production after filming was complete.

“As an editor, I feel like being on set can be harmful to me,” she explains. “I like to know what’s happening based on the footage and not because I was there and saw how hard it is that he’s working. There have been times when I’ll think a scene should be cut, but if I think, ‘Oh my God, they worked until two in the morning and there was a crane…,’ it’s harder to cut. It’s easier for me to be a little bit more ruthless if I haven’t been on the set.”

Lepselter does not claim to be prophetic about which Allen films will make an impact with the public. “I loved Midnight in Paris, but I thought it might be a little more esoteric than it proved to be for mainstream audiences,” she said. “So I was really happily surprised that it reached so many people.” On the other hand, she was taken aback by the commercial failure of Cassandra’s Dream, a drama centered on an uncle who prevails upon his nephews to commit a crime. “That’s the one that surprised me the most,” she says. “I enjoyed it so much, but it really didn’t find an audience.”

Hit or miss, however, Lepselter continues her collaboration with one of America’s foremost filmmakers, including on A Rainy Day in New York, due next year. “This is the long haul,” the editor reflects. “Woody likes to work with the same people over and over again.”

From Rosenblum and Kalish, to Bricmont, Morse and Lepselter, Allen has always worked with talented editors (some for lengthy tenures) who have enhanced — and more than once reimagined — the sometimes comic, sometimes tragic and always inventive material he gives them.