by Edward Landler

As the upcoming film Moneyball makes expressly clear, Baseball is a game of statistics––something rarely, if ever, touched on in any of the movies about the sport since the first Baseball movie arrived in 1898. Far beyond any other sport, virtually every bit of action in a baseball game, season and career can be summed up and com- pared in precise numbers, all of which will end up in the record books. Offering end- less fascination to fans, the statistics also give Baseball a kind of continuity that is unique in the history of American team sports. It’s a fair guess that a lot of kids learned more about percentages from following Baseball than from school.

But, in over 150 years of continuous popularity in America, Baseball’s statistics cannot explain what draws players and spectators to the game. Three things attract us to the game and to the movies about it:

* No other sport combines team play and individual virtuosity with such seam- less elegance.

* Few other games provide players and spectators with such sharp and sudden contrasts of the predictable and the unexpected.

* No other sport is embedded into our collective consciousness from early child- hood on as the Great American Pastime.

Most baseball movies simply accept these things and use the game as a set- ting for the development of a story and its characters that can be played out against many different backgrounds. But, the best baseball movies explore these ideas and lend insight into how the game itself influences the characters and reflects American culture itself.

Early in the 1949 musical Take Me Out to the Ball Game, Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra and Jules Munshin turn a dining room into a ballpark as they sing “O’Brien to Ryan to Goldberg” to extol their double-play prowess and make an exuberant point about the charm of the game. Set around 1900, the movie glows with American nostalgia, like President Teddy Roosevelt throwing out the first ball at the first game of the season (though William Howard Taft was actually the first president to throw an opening ceremonial pitch in 1910). For the closing musical number set in a theatrical show, there’s even a back- drop with a baseball stadium painted red, white and blue.

A turn-of-the-century clambake on a waterfront landing turns into the film’s biggest musical number, “It’s Strictly USA” by Betty Comden and Adolph Green. The company sings vigorously what it’s like to be American—“…like a brass spittoon, like Daniel Boone, like Mr. Sambo and Mr. Bones…”—an unintended yet accurate reflection of racial attitudes for both 1900 and 1949, two years after Jackie Robinson crossed the color line in Major League Baseball.

The only other baseball movie musical, Damn Yankees in 1958, shows some advance in the depiction of race while underscoring Baseball’s entrenchment in American life. Early in the movie, the screen fractures into six different living rooms with six different couples all singing, “Six Months Out of Every Year.” The wives bemoan losing their husbands to Baseball while the husbands sit fixated on their TV sets—one of the couples is black and one is Japanese.

Surprisingly, these are the only base- ball movie musicals. In Damn Yankees, especially, the two musical ensemble numbers (choreographed by Bob Fosse) with the film’s Washington Senators ball club—“You Gotta Have Heart,” sung and danced in the locker room, and “Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, Mo,” performed out on the diamond—vividly embody the balance and interplay between the player and the team at the heart of the game.

The earliest baseball movies paralleled the rise of Major League Baseball as a national industry. Made through the silent era, their stories gradually departed from local, small-town team rivalries, characters and romances to big-city ball club dynamics. This movement is roughly exemplified in the career of the single most influential individual player in Baseball’s history and in two movies about him.

In 1920, the year after Babe Ruth was sold by the Boston Red Sox to the New York Yankees, Ruth starred as himself in a movie called Headin’ Home. Calculated to piggyback on his growing fame, it presented itself as the story of his early life. Instead of his real childhood spent in a harsh Dickensian Catholic orphanage in work- ing class Baltimore, the film showed him growing up in a pleasant rural town, where he carves his baseball bat from a tree branch. Though not a box office success, its version of Ruth’s life became an accepted myth for much of his career.

But when the Babe comes up to bat in Headin’ Home, the movie suddenly comes alive. At the end of the film, after he is established as a major league player, a crude but effective montage builds to the climax: An over- head shot of the diamond, a medium shot of Babe at the plate, close-ups of his feet at the plate, his eyes, his hands clutching the bat, long shot of the pitcher, medium shot of Babe connecting and running, an overhead of him circling the bases and, finally, the crowd overflowing from the stands to mob him on the field.

In 1992, John Goodman played Ruth in The Babe, a film biography directed by Arthur Hiller. In most baseball biopics, the game is secondary to the strength of character the films’ subjects show in facing their personal travails—Lou Gehrig’s dis- ease in The Pride of the Yankees (with the real Ruth playing himself to Gary Cooper’s Gehrig, 1942), Monty Stratton losing his leg in The Stratton Story (1949) with James Stewart, Jimmy Piersall’s mental break- down in Fear Strikes Out (1957) with Anthony Perkins. The Babe, however, deals honestly with Ruth’s personal life, unlike the saccharine and superficial 1949 The Babe Ruth Story with William Bendix that entirely omits the first marriage that came apart because of his career.

The Babe focuses on how Baseball itself as a career shaped Ruth’s personal life, but it also depicts how he changed the sport and its place in American life. His hitting changed Baseball from a game primarily based on strategies like bunts, steals, squeezes and hit-and-run plays to one more balanced with power hitting. His popularity helped diminish the effect of the 1919 White Sox game-fixing scan- dal, drawing record crowds to Yankees’ games at the stadium shared with the New York Giants; when Yankee Stadium opened in 1923, it was appropriately nick- named “the house that Ruth built.” His fame also solidified Baseball’s standing in the larger business world of national publicity and merchandising.

The one other biopic that deals seriously with the game’s influence in American society is 1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story with then-active player Jackie Robinson portraying himself. Its depiction of how he broke Baseball’s color barrier is remarkably blunt and honest about the racism of its time. When Robinson tours with the Black Panthers in the Negro League, he is sent into a diner to find out: 1) if the team can eat inside, 2) if not, can they wash up inside, and 3) if neither, can they at least order to go.

When the Dodgers’ Branch Rickey sets out to integrate Baseball—even though he keeps addressing Robinson as “boy”—he first places him on the Dodgers’ Montreal farm team, lauding his “physical capabilities as a human being.” The team’s man- ager asks, “Mr. Rickey, do you really think he is a human being?” Later, spectators in the stands taunt Robinson in the Dodgers dugout by holding out a black cat on a noose-like leash. Robinson takes the cat away from them and cares for it in the dugout.

The late 1940s and early ‘50s exhibit a marked spike in the number of baseball movies that is not matched until the ‘80s and the years following. Most of the films of both eras carry on three themes in their plots and subplots that first developed in the baseball movies of the 1920s: the maturing of a conceited star player into a willing team player, the effects of sexual liaisons and romantic love on the main character, and the intrusion of gambling in an honest game.

Bull Durham in 1988 combines the first two themes in a way curiously prefigured by a charming 1943 B-movie called Ladies’ Day in which pitcher Wacky Waters’ arm goes erratic whenever he has a romance. The 1984 adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural conflates all three essentially mythic themes of Baseball with an overlay of older mythological imagery from the legend of King Arthur. The ironic view of American values achieved in the novel’s tragic ending is undercut by a happy—and overly spectacular—ending in the film that completely belies the essence of the Camelot myth.

Shown (left): Bill Irwin (as Eddie Collins); (right) Gordon Clapp (as Ray Schalk)

The intrusion of gambling, though, is only the starting point for John Sayles’ 1988 landmark movie about the Chicago “Black Sox” scandal, Eight Men Out. A beautifully paced introduction inter- weaves the Chicago team playing on the field, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey talking to the press in the clubhouse and exposing to viewers how he ruthlessly exploits the players, and a conversation between two gambling speculators in the stands sizing up which of the players can be bribed. Historically accurate and consistently sharp in its depth of characterization, Eight Men Out also brilliantly utilizes depth of field to enhance its careful inter- cutting of POVs and reverse angles portraying the players in action on the diamond—probably the best visualization of team inter-dynamics in movies.

History lends substance, as well, to A League of Their Own, directed by Penny Marshall in 1992. Tracing the beginnings of the All American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1943, the movie creates a rich tapestry of lightly fictionalized characters drawn from the real players of the League, while highlighting the rivalry between sisters Dottie (Geena Davis) and Kit (Lori Petty).

Throughout the film, all the individual women’s physical strengths and skills as athletes are emphasized and played out against the background of the unconsciously accepted male chauvinism of the business interests backing the League. Closing with the aging characters—mixing with the actual women ballplayers—at a dramatization of the dedication of the Women in Baseball plaque at the National Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, New York in 1988, the individuals’ stories merge into a moving recognition of the ongoing changes in women’s stature in American life.

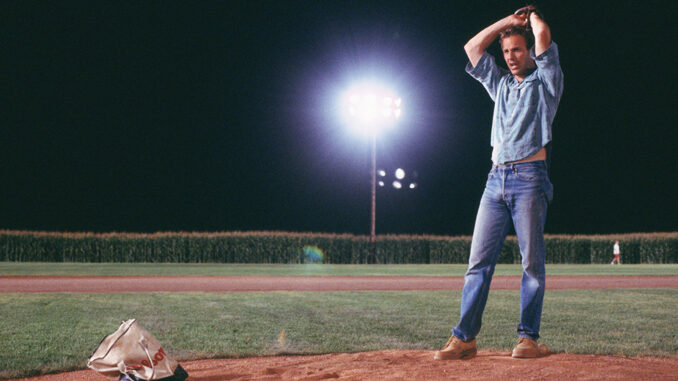

While history lies at the heart of 1989’s Field of Dreams, no particular era or play- er is central. Instead, Phil Alden Robinson’s adaptation of W.P. Kinsella’s novel uses film’s ability to manipulate time to make Baseball a metaphor for American culture. A voice tells Kevin Costner’s Ray Kinsella, “If you build it, he will come,” inspiring him to build a base- ball field on his family farm as it nears fore- closure. Encountering players from the 1919 Chicago White Sox emerging from the past, Ray embarks on a nationwide pilgrimage in his old Volkswagen van to find out why this is happening.

Writer-director Robinson creates a moving homespun surrealism that subtly intensifies as Ray not only meets more figures from the past directly affecting his present, but finds himself walking into other time periods. In the end, Field of Dreams transcends the baseball movie genre as it explores the conflict in the American soul between the values of home and social cooperation and the values of business and material success.

As Terrence Mann, the film’s fictional iconic writer of the 1960s counter-culture played by James Earl Jones, states: “The one constant through all the years has been Baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. Baseball has marked the time. This field, this game, is a part of our past… It reminds us of all that once was good and it could be again…”

At the heart of this game that has so worked itself into the heart of our culture is a model that reflects the American social ideal—the individual player whose strong singular personality shines through his intimate collaboration with all the strong singular personalities on the team. Curiously, perhaps, the movies’ most lyrical embodiment of the skill, the poise and the grace of the individual player is a three-minute sequence in one of Buster Keaton’s best silent comedies, The Cameraman (1928).

Keaton is an aspiring newsreel camera- man who goes to Yankee Stadium to photograph a game, only to find that the Yankees are playing in St. Louis that day. Alone in the “house that Ruth built,” he strides to the pitcher’s mound, looks around and starts to mime a game. From his actions alone, it soon becomes clear that he is pitching to a batter with runners on first and third. He holds the man at first back from stealing second. He signs and nods to the catcher, then pitches—watch- ing as the runners are put out at second and first. Then he runs home to tag the third runner out.

Stepping up to the plate to bat, Keaton dives to the ground to avoid a pitch thrown at his head. He recovers his imaginary bat to hit a long, long fly ball and circles the bases, sliding into a belly flop at home plate to score. He rises, dusts him- self off and takes his bows, doffing his cap to the empty stands…truly an American dream.