by Debra Kaufman • portraits by Christopher Fragapane

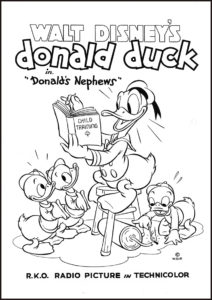

Longtime classic Disney character Donald Duck’s mischievous nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie made their very first appearance 82 years ago in a February 1937 Donald Duck Sunday newspaper comic strip (only three years after Donald himself was created). By October of that year, the triplets had their own strip, Donald’s Nephews, and six months later, in April 1938, the three ducklets made their animated debut in a cartoon short of the same name.

The characters endured, in print and on screen, throughout the decades. Half a century after their creation, they got their own television series, DuckTales (1987-1992). This was followed a few years later by another animated series, Quack Pack (1996), in which they were joined by their exasperated uncle Donald and ultra-rich grand-uncle Scrooge McDuck.

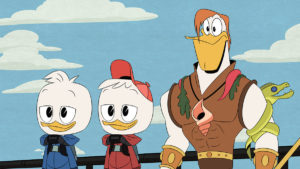

And then, when the characters turned 80, Disney rebooted DuckTales 30 years after the original series. The reboot includes many hen and drake characters, such as the triplet’s lady friend Webbigail “Webby” Vanderquack and chauffeur/pilot Launchpad McQuack, joining them in their in misadventures in Duckberg. Produced by Disney Television Animation, DuckTales premiered in August 2017 with a 44-minute special on the Disney Channel. The second season premiered in October 2018 and a new episode is set to air March 9.

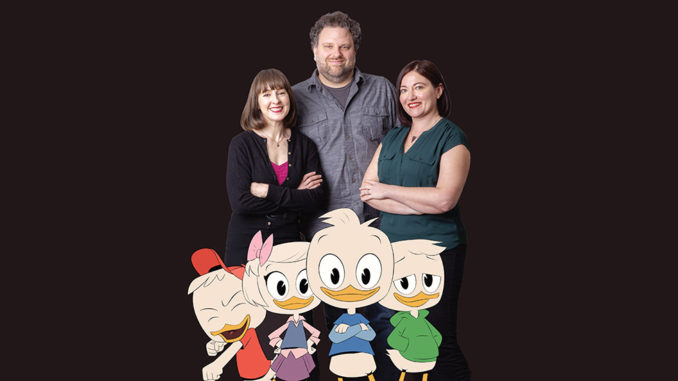

Over at Disney Television Animation in Glendale, it is fittingly a trio of animation editors who are hard at work on DuckTales: Jasmine Bocz, Barbara Ann Duffy and Mike Williamson (each works individually on an episode) — along with assistant editor Susan Odjakjian. Here are their origin stories:

Becoming an animation editor usually happens one of two ways: either falling in love with animation at an early age and finding a path to fulfill that dream, or falling into it by serendipity and finding it a comfortable home.

Bocz reveals that she belongs in the former category. As a child in the 1980s, she was obsessed with the original DuckTales on TV. “I taped the episodes on VHS every day and rushed home to watch them,” she recalls. “I fell in love with the craft of animation and started to teach myself how to draw.” She learned to edit on an Avid in high school and, when she went to Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design to study film, she interned for four summers with Disney Television Animation.

Upon graduation, one of her film teachers hired her to be his assistant editor on Clifford’s Really Big Movie (2004). It was her experience with that film, as well as the four summers interning at Disney that cemented her desire to work in animation. After some twists and turns, she became an assistant editor on the animated series TRON: Uprising (2012-2013).

Duffy actually grew up in a family of animators — both her parents worked for Klasky Csupo — but after film school, she intended to pursue a career in live-action editing. “As fate would have it, I was between jobs and a live-action assistant editor job for a commercial came up at Klasky,” she says. “I jumped on that and was an assistant on a McDonald’s short called The Wacky Adventures of Ronald McDonald: Scared Silly [1998].” Her animation credits include stints as an animatic editor on the TV series Rocket Power (1999-2004) and As Told by Ginger (2000-2006)

Williamson is solidly in the second category. He started out his editing career cutting live-action and transitioned from assistant to editor working on scripted and unscripted television, including Deadliest Catch: Dungeon Cove (2016). “I was a bit burned out on unscripted and found myself looking to move into another kind of editing,” he concedes.

He ran into a friend who worked at Disney Television Animation and got an interview on Pickle & Peanut (2015-2018). “That was a really fun show and my introduction to animation editing,” Williamson acknowledges. “I’ve always been a fan of animated film and television, and the opportunity to work with so many gifted artists within the unique animation pipeline made staying in animation editing a no-brainer for me.”

For her part, Odjakjian was inspired to go into film editing at age 11 when she saw an Olympics highlights montage reel. She says her entire career has been in animation, starting in 1981 with Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids (1972-1985), followed by He-Man and Masters of the Universe (1983-1985) and She-Ra Princess of Power (1985-1987) at the legendary animation studio Filmation.

She recounts how, in the early days of her career, she was the only woman in the room. “The only reason I got into animation was because it was the only way I could get into editing,” she admits, recalling that, at Filmation “Editorial consisted of 20 guys and me. I got in that way and never left. I finally got in the union that way and have worked at eight animation houses in all.”

Animatic for the People

Much like the transition from Moviolas and flatbeds to nonlinear editing systems, the process of animation editing has transformed significantly over the years. Duffy recalls that when she started, she photocopied hand-drawn storyboards. “Animation editing has changed drastically in the last 20 years,” she stresses.

An entry-level job back then was a digitizer who started out photocopying hand-drawn storyboards to distribute them. “To get them into animatic form, we scanned them,” says Duffy. “I remember using a camera to photograph them and then put them into Adobe Photoshop, where they were cropped precisely, exported and then imported into Adobe Premiere. It was a painstaking job that would be given to someone just starting out in the industry — and that was me.”

In the completely pre-digital era, animation directors would slug the board, indicating how many frames they wanted each panel on the hand-drawn storyboard to last on screen, according to Duffy. “For series animation, every scene was cut on an even number, so that the animation would come back on twos,” she adds. “Directors used to time it out in their heads.” As nonlinear editing became commonplace and accepted, so did animatics, although the earliest animatics were “very rudimentary.”

Animation editing today is a two-part process: First the storyboards and recorded dialogue are married and transformed into animatics. The actual animation takes place overseas, and when the finished animation returns, editors do final color, which includes hundreds of retakes per episode.

But, say DuckTales’ editors, there is no single animation editing workflow, which differs by studio and by show. “Although some stages of our pipeline remain consistent, each production has to run some things differently, for multiple reasons,” says Bocz. Williamson notes that, whereas editing is already a mystery to most moviegoers as an invisible art form, “Animation editing is even more of a mystery — even within the editorial profession.”

The animation process for DuckTales starts with the raw dialogue tracks from the voiceover cast, broken into lines. “Building the animatic is the most labor-intensive part of the process,” Williamson attests. “There are no dailies with actors in a scene to start cutting immediately, like live action. I have hundreds of separate lines of dialogue and thousands of storyboard panels. I also get the script and a PDF of the storyboards in order, so I know how the story is flowing and where the dialogue should be falling in the scene. It’s a more naked feeling than in live action, where you have the moving images and the sound married from the get-go. In my timeline when I’m starting an episode, it’s a void.

“It’s almost like writing a script when you start with a blank page,” Williamson continues. “Here, in the animatic stage, it is up to me to marry all these images and sounds and make a show out of it.” He notes another thing lacking in animation compared to live action. “In live action, you’ll have a performance with interplay between characters, and comedic timing built in within a master shot perhaps, and then you cut from there,” he explains.

“In animation, with the dialogue performances all separated individually, the editor decides the timing between every single line of a character,” he adds. “There’s a tremendous amount of freedom in sculpting a performance because the media is so raw. There’s an artistry in that, but it’s also nebulous as to how it’s going to land — and nobody knows until it is put together.”

DuckTales is a very script-driven show, according to Bocz. “The story is really fleshed out in the script phase and it creates a good guideline for the storyboard artist to plan out the scenes,” she says. “The animatic phase is both complex and time-consuming. I’m building the boards from scratch and, for me, that’s where I feel I’m the most creative.”

“I’m really pacing out the story and working closely with the director to see if the jokes are playing and the action is working,” she adds. The most arduous aspect of creating the animatic, according to Bocz, is to “take these storyboards from an incredible team of artists and make sure I’m interpreting their meaning and their intention of how the scene should play out. I’m starting with zero sound, zero music. We’re taking stills and have to breathe life into them, which is both challenging and rewarding.”

Bocz considers animation editing a very specific skill. “Editing for me is a gut feeling; it isn’t that a walk cycle should be a certain number of frames,” she says. “There are guidelines, of course, but more than anything to me, it’s a sensibility. It’s something you feel and you are either the kind of person who gets it or you don’t. I visualize and know what I’ll react to when I cut it. I have to mentally imagine what these stills will look like when fully animated to know how many frames each one should be on screen for. I can’t say there’s a science behind it; it feels more intuitive.”

She notes that every editor has her or his own process. “Mike works panel by panel, where I might lay them all out as a uniform number, start watching and then pace it from there,” Bocz explains. “I’m not in the room with the other editors so I don’t know their creative process. It’s personal preference, but we all work very closely with our directors to finalize the feel of the actual animatic.”

She also points out that part of the freedom of editing the animatic is the ability to add to the storyboard. “If we feel like we need a close-up or a wide shot, we can decide to do that before getting back the footage,” Bocz offers. “I remember when I was cutting live action, I’d wish I had a specific angle and it was too bad that I had to make do with what was shot. In animation, you can see that before money is spent on the animation.”

For Williamson, the show’s narrative style is an adventure. “There are stakes, but it’s also lighthearted,” he says. “It’s a balance of making sure it’s funny but also ensuring that the drama is legitimately landing. It’s not a goofy show just for the younger kids but one intended for the whole family to enjoy, so there are dramatic moments for the older kids. You have to make sure you respect the story, top-to-bottom, and tell it honestly.”

He adds that the DuckTales episodes are “pretty big,” capped off by a “completely action-packed” third act. “The amount of panels we have is huge,” he says. “I approach it by making sure this animated TV series plays as thrillingly as any feature film I’ve seen this year — to cut aggressively when it needs to be aggressive and delicate when it needs to be delicate. The animatic stage is where the lion’s share of the storytelling gets shaped before the animation, which is why I cut in a way that conveys the emotions and set pieces clearly.”

Multiple Retakes

Once the directors and executives sign off on the animatics, the actual animation is created in Korea. When the animation returns, it’s the job of the editors to assist in identifying and even fixing a number of the hundreds of retakes required for every episode. How the DuckTales team handles it is different than other shows, notes Duffy. “We’re a special team because we are the animatic editors and also the final picture editors,” she explains. “We’re one of a handful of teams at Disney TVA that’s been able to do this successfully, and I don’t think this is typical. But it’s working really well with us, which is a pleasure. We know the animatic so well, it makes it smoother for cutting the final picture.”

This is where Odjakjian comes in. “I work on color rather than animatics,” she says, noting how much she loves working on a 2D show with legacy characters. “When the final animation comes back in color months later, I assemble the show and sync it up. Then the editor and director cut it down to time. When that’s locked, the director goes through it again, and he calls for hundreds of retakes. One two-episode show had almost 1,000 retakes.”

Retakes for a single episode can take up to six weeks, as the overseas animators and local technical directors redo them, according to the assistant editor. (Here, technical directors refer to in-house artists who revise scenes after they have returned from the animation studios; these are not to be confused with the Guild classification of technical directors, who work in live TV.) “When they arrive, I cut them in, match the cut and then review them,” Odjakjian says. “If there are enough changes, I send another locked version to the dialogue, music and sound effects editors.”

Hundreds of retakes for a single 22-minute episode seems excessive, but, says the editorial team, there are many reasons for it. “Every time Donald Duck is drawn, he has to stay on model,” Odjakjian explains. Because so many animators are drawing Donald and his nephews, inevitably many frames show them with inconsistencies. Retakes also include techniques “to improve the look or the flow,” such as color pops and frames that may be needed to “hook up” one scene to the next.

When the animation returns to the editors, “Sometimes it’s vastly different interpretations of what I knew the director wanted,” Duffy points out. “It’s both a creative and a mathematical formula that can get reinterpreted every time it gets into new hands, so the chances of getting lost in translation is entirely possible,” she says. Some retakes involve creative issues — “such as something we wanted originally but changed our minds about — or it can be a joke missing or continuity errors.”

Consecutive scenes might be assigned to different animators, so when Scene A joins to Scene B, there can be stylistic issues. In that case, “We will sometimes call multiple retakes for the same scene, resulting in a process that goes on for several months,” Duffy says. “Sometimes we get retakes past the point we lock. The show is very concerned about quality for very good reasons. It’s thoughtfully produced and it looks beautiful.”

Once the editors match all their color “take ones” to the scenes that make up the animatic and do a creative pass, they sit with the executive producer to cut their episodes down to time. “From there on out, it’s multiple retake meetings,” maintains Duffy. “We look at the retakes and decide if it needs to go back overseas or done in-house. Once we have it as close as we can to final picture, we have a playback session for final notes from everybody — from the art director to executives.” During the retake back-and-forth, says Williamson, the composer is working on the score against the editor’s cut and the sound designer is also at work.

Those editors who dedicate themselves to animation enjoy the workflow that offers creativity and the satisfaction of seeing the project from the very beginning until the very end. As Bocz noted earlier, she feels most creative when building the boards from scratch. “Post-production [after the animation returns from the studios] is also nice, because I get to make sure it’s paced out the way I feel is right and have the ability to enhance individual shots so they look their best,” she explains.

For Williamson, “It’s creatively satisfying to see the episodes through, from animatic to color to delivery. There’s an almost limitless ability to tell the story knowing we’re not tied to our footage yet. That’s the great plus of working on DuckTales.”

On the television screen, the troublous trio of Huey, Dewey and Louie might be distressing Donald, but in their show’s cutting room at Disney TVA, the workload, challenges and demands on the editorial team are like…well, water off a duck’s back.