By Karen Dale Greene

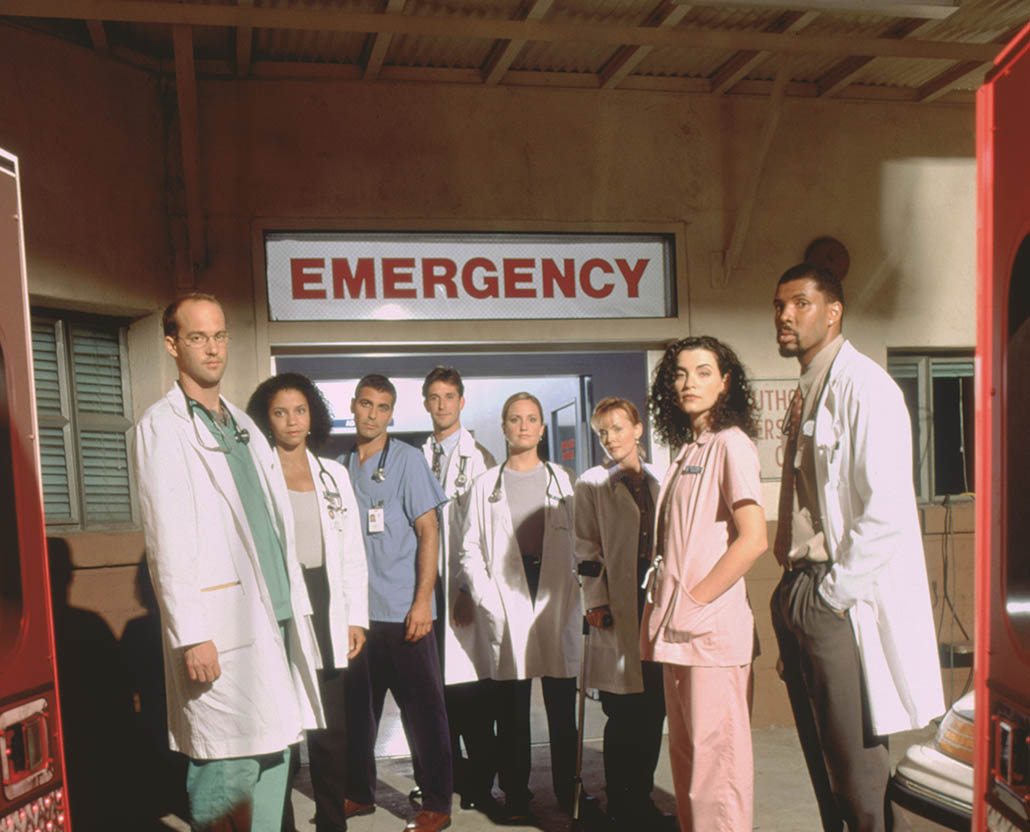

I have assisted Randy Morgan ACE consistently since the ER pilot and during the three seasons that followed. Throughout that time, I have always known him to be generous with his knowledge of editing. Between digitizing, cutting and locking shows, I managed to pick his brain about the art of editing. Randy has just won another Emmy, for his work on ER –“The Long Way Around”

Karen: What is the most important thing you keep in mind when cutting a scene

Randy: The story. The story means everything. I never just cut to cut. I only cut if it helps me as a storyteller. The script gives me the story that I need to tell, the film that is shot becomes my tool. As the story teller, It’s my job to figure out what’s the best way of telling the story, given the film that’s been shot.

Whether I’m working on film or the electronic systems, that aspect remains the same. The one distinct advantage that electronic editing has over film is the ability to experiment with cuts and pacing, Speed in itself isn’t always an advantage – just because the audience can absorb material very fast doesn’t mean you want to work against the pacing of the scene. The script tells me what the scene is about and if it’s a slow dialogue scene, obviously, I don’t want to have a lot of flash cuts, I adopt the pace that the story requires, It’s just that the Avid allows me to experiment more with that pace, that’s the real advantage.

“You could never have done ER on film, or if you had, it would have resembled more closely every other hospital show.” – Randy Morgan

Keeping stage lines clear

Karen: What do you feel are some of the special challenges to cutting an episode of ER?

Randy: The regular story lines are shot pretty much like any feature, TV movie or episodic show. That seems to be the direction that ER has started to take in developing so many characters and their stories. Obviously, in satisfying the public’s desire to find out more about those characters, ER has started to resemble the kind of shows that it was so far ahead of a few years ago. The shows have slowed down a lot, and more and more of the scene are starting to be analogous to those you might see on any other hospital show.

As far as the trauma scenes go, that’s where the biggest challenge as an editor lies.

Karen: What is unique about ER and the way you approach the material?

Randy: I’m not aware of any special approach. My attitude toward editing has always been a knee jerk reaction to first, what the scene is about and second, to the film that’s been shot to cover that scene.

In the case of ER, the director of the pilot, Rod Holcomb, found a really unique way to shoot all the trauma scenes. He used lots of Steadicam and handheld shots rather than just your conventional master and typical coverage. And with handheld shots, he was able to bring the audience right onto the center of the action and move the camera around in order to see the action from as many different viewpoints as possible.

On the pilot, the approach to the editing was simply a response to how Rod had shot the film in the first place – trying to use all the different types of footage that he had shot in a way to tell the story clearly without confusing the audience.

Typically, a master in ER is shot with a Stedicam and continues to circle around and around the action. First they shoot it on Steadicam with a wide angle lens, and then they shoot exactly the same master with a longer lens to give two different sizes of the same master which is not a master in a conventional sense at all. The camera is continually moving around the action so I never have one stage line established. My stage line keeps moving. When I cut into coverage, if I ever want to cut back into those masters, either the tight master or the loose master, I have to keep in mind where my stage line is when I drop back to it. It’s very easy to get everything twisted around and confuse the audience.

Karen: Do you have a systematic way you go about cutting trauma scenes?

Randy: Yes. There are just a few basic rules of thumb. Always cut to the person who’s talking, as a general rule. I try to use a moving shot as opposed to a static shot if I have a choice. A moving shot is more dynamic since I’m coming off a moving master. I try to use wipes and swish pans to my advantage as much as possible. I have to keep stage lines clear in my mind because if they’re not clear in my mind, they’re certainly not going to be clear to the audience. If I confuse people, they’re going to zone out.

Karen: After you have the picture in place, how do you apply the use of sound to pacing in the traumas?

Randy: After I finish my first cut of the scene, I go back to though and A-B all my tracks. Then I start tightening the scene as much as I can without having it be cutty and still have it make sense. I then allow the dialogue to start crossing over.

“[Electronic editing] has split the partnership of two people working on the same job. Instead, the situation has become two people with two separate jobs – the two jobs being dependent upon, but exclusive of each other.” – Randy Morgan

When I start crossing over lines of dialogue, I concentrate on giving track priority. If I have an argument scene going with everyone trying to talk at once there is really no telling how much you can overlap dialogue. Sometimes it just sounds better and better the more overlapped it is. I want both sides of the conversation to be understood. When I finally have my sound working, I go back to my picture and adjust my cut, and try to find the best possible place to cut the picture in order to keep it in sync with the track.

When I do that, I want to keep the dialogue from becoming jumbled. I always want there to be enough information there so that the audience can follow every single line. If they cross over, that’s fine, but they still have to be intelligible.

Pros and cons of electronic

Karen: Do you feel ER is a product of the electronic systems?

Randy: You could never have done ER on film, or if you had, it would have resembled more closely every other hospital show. Despite the way it was shot, your approach would have been much more conventional in the old ways of approaching the editing of a scene.

On film, I would have never attempted to A-B the sound tracks. I would have gone with just the one track unless there was some place that obviously needed an A-B track to bring the action together. The one linear single track would have, to a certain extent, dictated the pace of the scenes. On the Avid, I can drop down to three and four tacks of principle dialogue at once, and it has allowed me to have multiple tracks going at one time and really pick up the pace.

Karen: Avid seems to have helped you a great deal in the creative process. On a more human level, how have the electronic systems affected the editor/assistant relationship in the cutting room?

Randy: It’s been a disaster for the conventional editor/assistant editor relationship. Of course, apprentices have become a thing of the past.

Karen: What is the best way for an assistant to make the transition from assistant to editor?

Randy: Moving up requires more commitment than it ever did before. On the electronic systems, the availability of the machine is limited. The assistant has to make time to cut and come in at odd hours and give more of themselves to obtain editing experience because they’re not going to get it in the course of the day. Even if they have slack times, they can’t get access to the machine.

Editor-assistant collaboration

Karen: How will we be able to pass on the art of editing within the electronic environment?

Randy: One of the problems that this environment has created is that it has split the partnership of two people working on the same job. Instead, the situation has become two people with two separate jobs – the two jobs being dependent upon, but exclusive of each other.

Whereas before, the editor and assistant editor could collaborate, now the assistant goes in and does the mechanical chores and then the editor comes in and does the “creative” part of it. Then the assistant comes in and does more mechanical things. The assistant never really gets a chance to actually do editing. In my case, once the assistant is done putting dailies into the machine, I want to start cutting. I realize that is probably not fair to the assistant, but what I keep in mind is the schedule of the show.

“I never just cut to cut. I only cut if it helps me as a storyteller.” – Randy Morgan

By the time I leave every evening, I’m usually up with dailies which means that when the assistant comes in the morning there’s really nothing left for her to do except digitize the next day’s dailies. I’ve learned to loosen up on that a little bit and leave scenes for the assistant and allow myself to take an extra hour or two off the evening and leave work for her to do in the morning. But I have to be sure it’s something she will be able to complete while working around my time on the machine and her own duties.

On film, I was very open to assistants cutting sequences and I encouraged them to do so. It didn’t affect me in the least. In fact it helped me, and I had one less scene to cut.

With the shortness of schedules on television shows there simply isn’t time to allow someone else to come in and start cutting. And I see the same thing happening on features, with post production schedules getting tighter all the time.

On ER, my assistant and I share one machine. The ideal situation would be if there were two machines. However, the systems are so expensive that most shows don’t want to give the assistant his or her own station. And the so-called assistant stations are very limited and can’t be used for editing at all. Assistants just don’t have a place to work as they did on film which is counterproductive to their growth process. There will be real difficulties as far as assistants getting the editing experience they need to eventually move on to become editors in their own right. It can still be done, but as I said, it will require more commitment on the part of assistants and the help and understanding of their editors.