by Kevin Lewis

Documentarian Robert J. Flaherty was regarded by the poet e.e. cummings as “a god among men,” an opinion echoed by Orson Welles, who compared Flaherty to the poets Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau. Today, Flaherty’s sanctified legacy lives on through the Robert and Frances Flaherty Study Center at Claremont College in Southern California. Although he will always be regarded as an essential figure in film history, to many educators and succeeding generations of documentary filmmakers, Flaherty’s pedestal has feet of clay. The term “Father of Documentary” has been charitably reduced by academics to the term “Documentary Pioneer.”

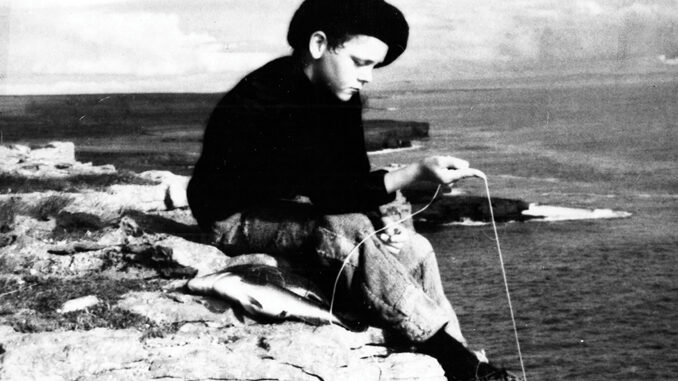

In April, Man of Aran (1934) will be 75 years old and is probably Flaherty’s most popular and widely shown film, particularly since it is available on DVD from Home Vision, along with a brilliant documentary on the production, How the Myth Was Made (1977) by the esteemed documentary filmmaker George Stoney. Stoney, who in his 80s is still teaching film at New York University, has an affinity for Man of Aran because it is intimately intertwined with his own family history. His grandfather was the physician on the remote Irish Aran Islands and his father was born there.

Flaherty himself was born in 1884 in Michigan, the son of a miner who dragged his son around the Canadian wilderness working for mining companies. When he became a filmmaker, his films were commissions from such major corporations as Paramount, MGM, Alexander Korda, Gaumont-British and Standard Oil. Though he was regarded as an anthropologist on the level of National Geographic, there was much of the Great White Hunter in his perception of the world. The principles of 19th century imperialism shaped his films. Even his breakthrough documentary, Nanook of the North (1922), about the Eskimos, was re-staged to include more primitive forms of hunting seals than the Eskimos used at the time. The Eskimos used rifles rather than harpoons by the 1920s, but Flaherty thought the harpoons were more roman- tic and mythic.

The romance of people left behind is central to Man of Aran. The film is a beautifully shot (by Flaherty) black-and-white film, but it never was an accurate depiction of the Irish. Stoney tells Editors Guild Magazine that “Flaherty regarded them as primitives,” which fit in with Flaherty’s Rousseau-ian view of the noble savage. He regards the film as a historical piece, and says his students “struggle to find a narrative” when they view the film.

When Stoney interviewed the film’s editor, John Goldman, Goldman revealed his own frustrations working with Flaherty. Goldman had trouble editing the movie because, as Stoney reports, Flaherty could not give an editor the links necessary to edit a sequence in a sound film. Editing was simpler and more abstract in the silent era because missing narrative elements could be covered with a title card. The sequences in Nanook of the North and Moana (1926) could send audiences into reveries because the compositions were like paintings, and the action could be explained by title cards. Aran also employs title cards, which were more awkward in sound films, but could be forgiven if the visuals were poetic.

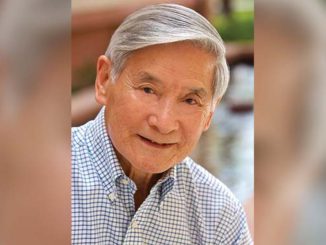

Flaherty, who died in 1951, was more successful with his last masterwork, Louisiana Story (1948), because of the gifted and sympathetic editor Helen van Dongen and his cinematographer Richard Leacock, who understood his inability to cut sound film to fit a soundtrack. The director may give the film its inspiration, but the editor gives the film its shape and form, its skeleton.

Arthur Calder-Marshall interviewed Goldman for his biography of Flaherty, The Innocent Eye: The Life of Robert J. Flaherty, published in 1963. Goldman, who also edited under his assumed name John Monck, was hired by Michael Balcon, who produced Man of Aran for Gainsborough/Gaumont-British. Balcon was impressed with Goldman’s editing because he had studied the film editing of Sergei Eisenstein and V.I. Pudovkin in the Soviet Union.

Goldman, who admired Flaherty, soon realized that the documentary filmmaker, who had been his own editor on his silent films, did not understand the linkage of shots and regarded editing as alien to his vision. It was difficult for Goldman to edit the film because, for example, Flaherty would pan the camera across the expanse and height of a cliff. Goldman told Marshall, “It was typical of him to try to do this by the camera rather than by cutting. His feeling was always for the camera. This wanting to do it all in and through the camera was one of the main causes of his great expenditure of film––so often he was trying to do what could not in fact be done.”

Marshall wrote, “If Goldman explained he wanted a link shot, say, between a man leaving a cottage and arriving at the seashore, Flaherty would say, ‘No, the camera doesn’t want to shoot it…the camera doesn’t see a shot like that.’ Flaherty was ever looking at the film through the camera. Goldman was thinking of what would be on the screen. ‘Cut away to something else,’ Flaherty would say, but if there was nothing to cut away to, Flaherty would reluctantly agree to shoot a link.” Though Flaherty was remarkable as a cinematographer, Goldman thought he “had no sense of the rhythm of film.” Marshall wrote, “[Flaherty’s] delight was in the shot per se, not in the cumulative effect of shots arranged in a particular way.”

“The hallmark of Flaherty’s work is the poetic vision of reality that he renders,” says Ron Sutton, Professor Emeritus of Media Studies at American University. “The incidents that he presents are his reality and nothing demonstrates that more than the dramatized shark hunt.” To Sutton, the famed shark hunt, which had not been practiced on Aran for over 50 years, appears phony because the island fisherman (which included assistant director Pat Mullen, who published his own book on the film called Man of Aran in 1934) knew this was not their reality. The end of that sequence, where “they really appear to be in danger as they struggle with the nets against the waves cascading over the rock,” is where the movie still works for Sutton because reality always trumps romanticism.