By Tris Carpenter

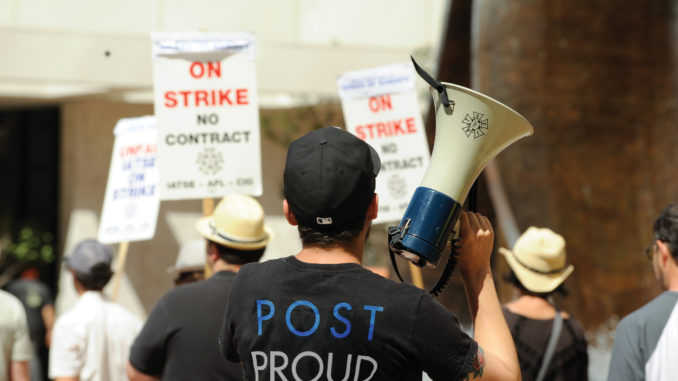

I recently attended a panel discussion between Peter Hurtgen, former member of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and former director of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, and Jon Hiatt, general counsel of the AFL-CIO. The subject was the future of labor law, the NLRB and the courts. While they did not see eye-to-eye about most things, both agreed that the NLRB is becoming increasingly irrelevant for workers in the United States.

When the National Labor Relations Act (the law creating the NLRB and providing the union election system by which much organizing has been done) was passed in 1935, most—if not all—work in this country was done in a very traditional manner. People had an employer and a workplace to which they reported five, six or seven days per week; they might be employed for several years. Even entertainment industry workers, at that time, did not have the mobility they are now required to have.

Of course, most post-production employees have gone almost completely freelance since then, and have been that way for many years. But, for most Americans, the difficulties of the freelance worker were pretty much unknown until the advent of the “entrepreneurial spirit” of the dot-com industry and its subsequent crash a few years ago. More and more people are offered the chance to get a bigger piece of the reward in exchange for a bit of sacrifice now, but the problem is that the reward often evaporates before they get there.

Hurtgen and Hiatt both argue that, as the traditional workplace changes and takes on more of the characteristics that have traditionally been experienced only by freelancers, the NLRB becomes more and more irrelevant. Because NLRB election procedures and methods for adjudicating disputes often take years, many employees find that the NLRB holds little hope for them in terms of solving their problems.

For much of the IATSE, the NLRB hasn’t been relevant for some time. Most motion picture organizing is done when crews walk off during production; very few companies go through the entire election process, then proceed to protracted negotiations over a contract. At the Editors Guild, we have used the NLRB when more direct (and dramatic) approaches were not available—but usually only as a last resort.

With no relief in sight from the government, we are forced to continue as we have—by organizing groups into strong units.

The consequence of trying to rely on the NLRB as little as possible is that Guild organizers require crews to be very committed to the goal of unionizing. Crew members who cannot withstand the pressures of an intense campaign by the employer to sway them away from Guild representation will simply not be moved on to the next step of asking the employer for recognition. It’s not so much a question of winning elections as it is building a stronger union; unless the group being organized is strong, committed and outspoken, they stand little chance of getting a good contract.

The obvious way to remedy the situation would be to limit the pressure employers can bring to bear on employees. That would require a serious reform of the nation’s labor laws, and again, Hurtgen and Hiatt both agree that such reform is unlikely for several years and certainly not under the current Bush administration. And even when such reform seemed possible—back in the early 1990s when Democrats controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress—it still never made the priority list. Neglect of labor’s most pressing issue—the difficulty of organizing the unorganized—has been bipartisan.

With no relief in sight from the government, we are forced to continue as we have—by organizing groups into strong units that can and will join the Guild in the fight for a better deal. There is simply no magic bullet that will slay the monster.

The saving grace for us is our members. While they often work for non-union companies, they can and do help us to organize. This situation, which does not occur in many industries, is one we try to use to full advantage. With your help, we will continue to break new ground (with or without the NLRB), keep organizing new companies and building a stronger IATSE and Motion Picture Editors Guild.