by Edward Landler

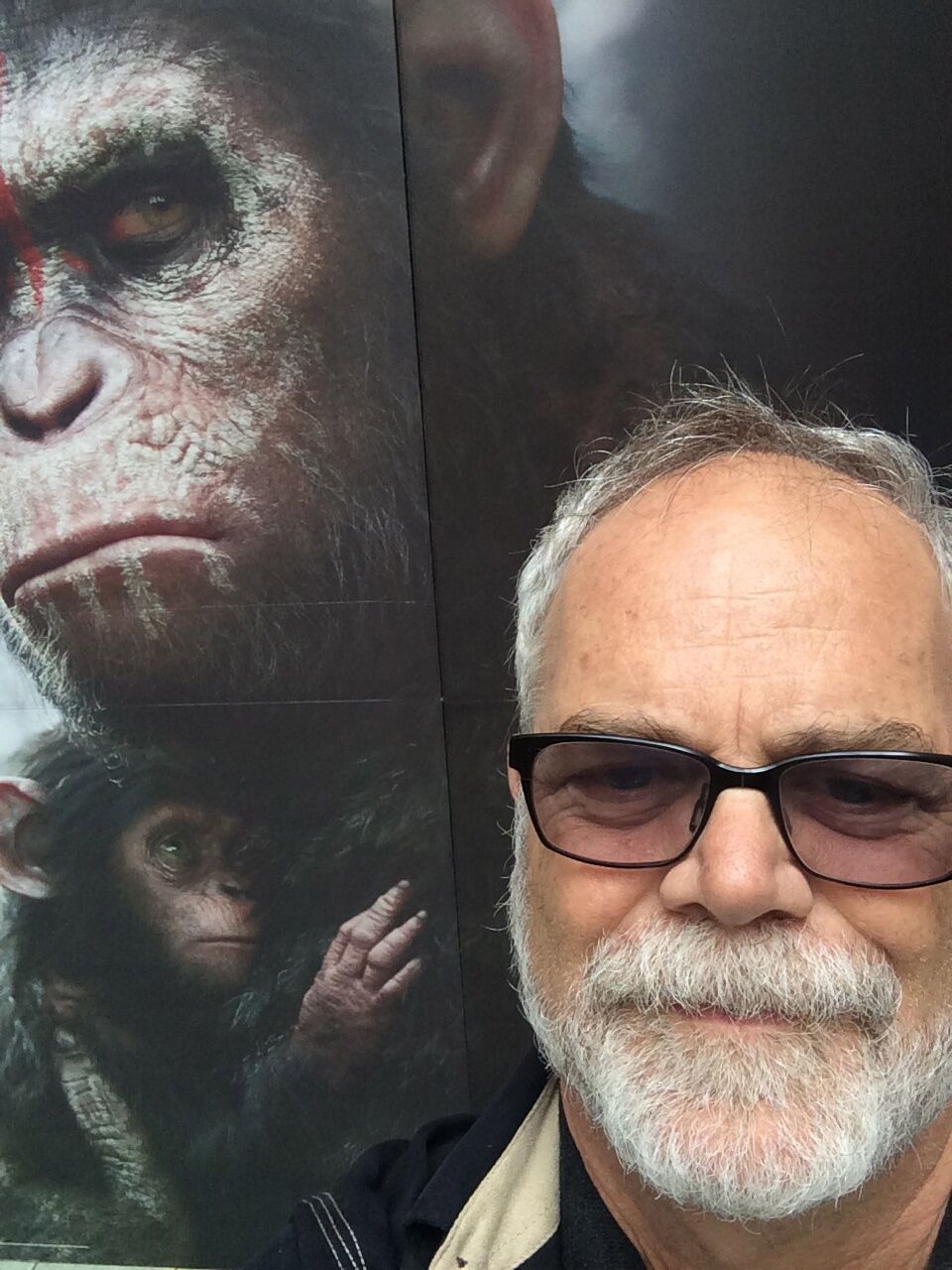

War for the Planet of the Apes, the third chapter of 20th Century Fox’s latest reboot of the Planet of the Apes franchise, opened July 14, almost three years to the day after Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, the second in the series. Since Dawn, director Matt Reeves has worked continuously on War, from writing the original screenplay with Mark Bomback (based on characters created Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver) through production and post to premiere.

Seamlessly blending footage shot in the monumental Canadian Rockies with flawlessly natural-looking visual effects and the most advanced motion capture technology to achieve a lifelike authenticity in its ape characters, along with resonantly constructed sound effects and an evocative score, the movie provides a thoroughly immersive experience for the viewer. Literally thousands in cast and crew (the majority in post-production departments) helped Reeves stage this immense on-screen and off-screen adventure.

For an overview of the massive task of mounting such a project, CineMontage sought out eight Guild members who held key post-production positions on the making of War. While highlighting the skills of these veterans, their conversations pointed out how they integrated their crafts — picture editing, sound editing, sound design and supervising, Foley, music editing, re-recording and mixing — into an organic whole.

After completing Dawn, picture editor William Hoy, ACE, kept in touch with Reeves about the next Apes movie and joined the production in Canada a week before the October 14, 2015 start of principal photography with cinematographer Michael Seresin, ASC, BSC (also on Dawn), shooting digitally with a 65mm Alexa. On the show for the next 21 months, Hoy said it was “the longest I’ve worked on any single picture.”

Editing scenes on location as footage came in, he realized that, unlike the first two franchise installments, War would be “almost entirely ‘ape-centric’ and the Caesar character [played by Andy Serkis] would provide the thread of emotions that had to be followed throughout the story.” Concentrating on Caesar and other major ape characters, he said, “I had a chance to map out how to make transitions as smoothly as possible through their POVs.”

Motion capture, however, added another factor to the editing. With actors in motion capture suits in virtually every scene, every single shot with these ape actors had to be photographed three times: 1) with human characters and ape characters in mo-cap suits at the same time; 2) with human characters alone; and 3) with no actors at all for backgrounds. For both the second and third shots, the camera was programmed to remember every movement to create the full performance plate for visual effects.

“This gave us a wide range of elements available for every shot,” noted picture editor Stan Salfas, ACE, who also edited Dawn and has worked with Reeves since 1995. Salfas started cutting War on the Fox lot mid-February 2016 — about six weeks before shooting wrapped in Canada. He had already been viewing the Canadian dailies while finishing up on Now You See Me 2 (2016) and now he started working through the last sets of uncut dailies to help complete the first cut.

At the end of March 2016, Hoy returned to Los Angeles when production wrapped after a full month of shooting additional footage of the ape actors on the Mammoth Studios motion capture stage in Vancouver. Much later, in November, pickups and retakes were completed on a motion capture stage in Manhattan Beach. Still, 85 percent of the sets in the film were actual physical sets.

The editors’ first assembly was done in early April, coming in at a little over three hours. Shortly after that, the visual effects and animation overlays — including the mo-cap ape imagery — began to flood in from Weta Digital, based in New Zealand.

Working with Fox visual effects producer Ryan Stafford on all three Apes films (including 2011’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes), Weta visual effects supervisor Dan Lemmon and animation supervisor Daniel Barrett had researched ape behaviors and developed new ways of processing mo-cap material to get the natural reality Reeves wanted to see. They also used the geometric readings, lighting specs and other variables for each of the three versions of each shot to make the visual effects overlays more natural in the editing.

This especially helped the editors in matching eyelines throughout the film. “With the apes, we had to make sure to adjust their eyelines to carry the actors’ right emotions after their mo-cap suits were overlaid by visual effects,” Hoy said. “Early on, as shots were absorbed into the picture, we knew we could capture the emotions and characters of our ape actors. For a picture like this, with so many visual effects, to be dependent on character and emotion was a dream.”

In addition to the main ape characters, who were framed dominantly in shots, Weta would add other individual characters using mo-cap for backgrounds as needed, as well as CGI of apes in larger background groupings.

With the benefit of having labored through Dawn, director Reeves and the two editors worked out a more methodical way to approach the visual effects turnover process in War — in sequence, shot by shot. Individual shots could literally take months to progress from blocking through multiple stages to final renders. Salfas said, “Some shots alone took 14 to 18 hours per frame to render — for a film with only a handful of shots that did not require visual effects.”

This helped Reeves convince Fox to push back the movie’s release from July 2016 to this summer. The delay also helped the studio plan more economically to hire post personnel when they could be best utilized, a major consideration for a show in which at least half the estimated budget of between $150 and 200 million would go into visual effects.

For the next year, much of the editors’ work “was to refine scenes with layers and layers of visual effects,” according to Hoy. “And Matt was almost always sitting right beside me or Stan.” Despite the editors’ different working methods, Salfas credits his first assistant, Stephen Shapiro, and Hoy’s first assistant, Melissa Remenarich for “smoothly integrating our two crews.”

This integration was crucial during post, especially at those times when Reeves and the editors spent from four to six hours a day reviewing the visual effects iterations via long distance cineSync sessions with the Weta team in New Zealand. As the visual effects material came in, though, Hoy said it also “changed how we saw what we needed for sound and music.”

Salfas agreed, “Every time there was a new shot, there was a new iteration of sound we had to ask from sound effects.” As an example, Hoy cited the effects they needed for ambience in the humans’ prison camp for apes. Someone from the sound department was always available to know the editors’ needs, or Hoy or Salfas went to sound designers Will Files or Douglas Murray to tell them what they needed.

The integration of picture and sound took on the same kind of continuous interchange necessary in feature animation, with one big difference. As Salfas noted, “This is an animation movie but it needs to be authentic, not imagined. The final judge was Matt, whose standard was that it look and sound real. The sound people had to be ready to provide a lot of different possibilities.”

Sound designer/supervising sound editor/re-recording mixer Files joined the project with sound designer David Grimaldi in February 2016, as edited scenes became ready for sound effects to be set to them. Sound designer/supervising sound editor/ape voice pre-mixer Murray came to the show the following month. “Will and I worked as a team on three other shows with Matt,” Murray said. “Now, like on Dawn, we divided our tasks; Will supervised sound effects and I did the ape sounds.”

Heading up the sound department with Murray, Files said that they “marshalled the focus of our talented crew to understand the director’s tastes and desires, and got all the sound effects editors to work with the same aesthetic.” Affirming the picture editors’ view of Reeves’ approach, he said, “Authenticity — audio, visual, emotional — reigns supreme. There are plenty of moments in the film with stylization, but they must be authentic to the characters’ experiences. Matt wants it to work through every single moment.”

Throughout much of the 65 weeks of post, the supervising sound editors would eat lunch with the director and the picture editors. “It was a good way to keep up with what was going on with the visuals,” said Files. This helped ease the stress of having to constantly deliver new pieces of audio, multiple times a week, with bits and pieces coming in until the last day of final mix.

Post went on so long that schedules were arranged to provide coverage for the picture editors through the entire process. The two supervising sound editors took turns taking time away from the project early in the post schedule; meanwhile, Grimaldi carried on with the help of sound editors Jack Whittaker and P.K. Hooker to keep the sound updates flowing to the picture editing crew. Hooker, along with Doug Jackson, also worked on the apes’ crowd sounds as effects editors.

Having supervised all the apes’ dialogue and sound effects on two Apes movies, Murray has become an expert in primate sounds. “In our research, what I took to heart was that apes don’t jabber; they react with specific emotions to situations,” he explained. “For backgrounds, we recorded a loop group of actors, men and women, who could make the right range of sounds and get it right.”

While no real apes were in front of the camera, Murray added sounds of real apes on the soundtrack, including recently discovered archival recordings of juvenile chimpanzees from the 1970s. The ape actors — both those who had lines in English and those articulating only primate sounds — were recorded on set, though real ape sounds were later mixed into their voices. “Whenever possible, Matt wanted to use the original on-camera performance,” said the ape audio pro.

This applied, of course, to central ape characters, including Caesar and the orangutan Maurice, played by Karin Konoval, who studied orangutan sounds for her performance. Augmenting her voice was a prime example of the soundman’s skills. For Maurice’s long dialogue scene near the end of the picture, Murray said, “We cleaned it up, pitch-shifted her voice and added resonance by playing it through the Audio Ease Altiverb plug-in into a djembe, a large African drum.”

This worked so well that it was applied in varying degrees to all her dialogue. Originally, the sound editors had cut in real orangutan sounds throughout her performance but, in the mix, dropped most of them and mainly used Konoval’s treated voice. Murray also noted the contributions of ape dialogue/ADR editor Kim Foscato, who added the breath sounds for all the ape actors.

For the other major sound effects work, Files noted, “Sound effects have to function like music, with moments of tension and release.” One of the strongest demonstrations of the sound crew’s success is the climactic avalanche, overseen by Whittaker; a conscious decision was made to allow this to be the loudest scene in the entire film.

With the director insisting that nothing artificial should be added, the sound effects team sought to give it a completely organic texture. The Foley crew contributed elemental sounds of wood and snow. Purposeful distortions included the sounds of underwater turbulence and the roar of a Saturn V rocket launch. After layering all the sounds to create perspective, Files said, “We played out much of the sound in deep exterior reverb to reinforce the enormity of the event.”

Back in mid-March 2016 — 11 months before composer Michael Giacchino started meeting with Reeves about his score — music editor Paul Apelgren came to work on War. Part of the composer’s team since 2005, he started to arrange a temp score, viewing the assembly-in-progress of “beautiful shots with people in pajamas,” referring to the mo-cap gear. Just three weeks later, when the editor’s cut was screened in April, the beginnings of the music editor’s temp score were ready to be included.

Setting the emotional tone for the picture before Giacchino composed fresh music, Apelgren used Pro Tools to prepare the temp score. For its themes, he used elements of the composer’s score from Dawn and music from other sources that, he said, “wouldn’t throw Michael.” By the time the first director’s cut was completed in October, most of his temp score was already locked in place for the screening.

For screenings prior to the final mix, there were no real temp dubs. “Every time we showed the film to the studio or preview audiences, we mixed the entire cut for that screening [from the material received from the sound and music editors],” Salfas said. “Later, we used the Avid tracks from the screenings as reference guides for the final mix.”

By January 2017, the cut had come down to its current 2:20 running time, and two more sound editing supervisors joined the show: Dialogue/ADR supervisor (for human voices) R.J. Kizer and Foley supervisor John Morris. Kizer, unlike the other seven post personnel interviewed, had worked on Rise but not Dawn. For War, only two name human actors required ADR sessions; one of them, Woody Harrelson, was working on the “Han Solo” Star Wars spin-off in London (still in production). By setting up a remote location ADR session via Source-Connect, the audio was certain to be in sync with picture.

Working with Foley artists Dan O’Connell and John Cucci at their One Step Up facility on the Fox lot, Morris and Foley mixers James Ashwill and Richard Duarte recorded Foley material for virtually every scene of the film. Working closely with visual effects, the departments shared schedules and, said Morris, “The Foley was shot in the order that we got the visual effects or animation — scene by scene, rather than reel by reel.”

The Foley team started with scenes that had already been largely rendered and approved. “If I had a scene that was 80 percent complete, we could work on it and go back later to adjust sync if necessary,” explained Morris. All the Foley was mixed separately from sound effects and shaped by Foley editors Matthew Harrison, Willard Overstreet and Thom Brennan. It was then sent on to Files to blend in with sound effects, which was then sent on to the picture editors.

The main Foley sounds were those made by hands, footsteps, movements and the props. These sounds, however, were always modified by the different “flavors” of snow, grass, dirt, gear and other surfaces that they came in contact with on screen. Describing the tree breaks and falls and the misty cloudy snowfall of the avalanche created by the Foley artists, Morris remarked, “Dan and John are magicians. I don’t ask them what they use to make the sounds.”

Meanwhile, Giacchino finished scoring the music late in March, recording it with over 100 musicians early in April, while still making changes. Apelgren said, “It would have been impossible without Joel Iwataki, Michael’s scoring mixer since Star Trek into Darkness [2013] — he gave us all the options — and recordist Vincent Cirilli, Joel’s right hand and Pro Tools guru.”

After an April screening with the full score, and during the final mix, the music editor was in constant motion between the dubbing stage and his editing room to work out the cues that had to be updated. In the middle of April, another music editor, Jim Schultz, came on board to tag team with him. “Jim was so experienced he was able to set up right away and worked through the end of May,” Apelgren said. “He did some heavy lifting instrumental to completing the project.”

The final mix was done on Fox’s Howard Hawks Stage over about eight weeks from mid-April through early June 2017. Reeves, Murray, Files and re-recording Mixer Andy Nelson, CAS, who now joined the project, all agreed it would be an active Dolby Atmos mix. Two-time Oscar winner Nelson said, “The value of me coming in last is that I’m the freshest to it; I have no history with the show. I could watch the whole of it and be most concerned about how they intend the picture to play.”

As Murray, Files and Nelson had decided on Dawn, the principal apes’ sounds and dialogue were considered dialogue, regardless of their source. Sharing re-recording mixer responsibilities, Files was responsible for sound effects and background apes’ sounds, and Nelson for music and all dialogue. During the mix, the re-recording mixers and Murray worked with the active participation of the music editors, Morris, Kizer and, depending on which reel was being worked on, sound effects crew members Grimaldi, Whittaker, Hooker and Jackson. Meanwhile, in their editing rooms, Hoy and Salfas steadily churned out approved scenes for the mix. “If Bill and Stan found the time, they would come in, but most questions could be answered by just listening to their Avid tracks,” explained Nelson.

For the first two weeks, without Reeves, they did a complete rough pass of all eight reels of the show to serve as a base line. Then, from May 1 on, the director was a permanent fixture on the mixing stage, tackling each scene meticulously. Addressing concerns that “we clearly over-scored the movie,” as Apelgren noted, music was dropped wherever it was not necessary. “Where the actor’s performance carried the emotions across, we were able to strip away a lot of the music,” Hoy added.

“I was there to wrangle the on-set human dialogue tracks,” said Kizer, who even had to do a few ADR sessions during the final mix. He also observed that Reeves, ever intent on authenticity, kept asking Murray if a particular vocal was from an ape recording or from the actor. Feeding as many as eight channels of ape sounds into one fader for the mix, only the ape audio expert could tell the difference. Kizer commented, “Sometimes even he had to consult his Pro Tools session logs to be sure.”

The final mix wrapped on June 2. Two weeks later, the deliverables were completed. Now, War for the Planet of the Apes is playing in theatres for audiences to decide for themselves — if they need to — what is ape and what is human.