CAN BIDEN REPAIR TRUMP’S DAMAGE TO WORKERS?

By Rob Callahan

This year arrives laden with anxious hopes. We hope to endure and to put behind us a prolonged season of dark days defined by disasters. We hope to move beyond a year misshapen by a terrible plague — one that has disrupted our lives and thrown into the sharpest relief the shame of our inequities, leaving unnecessary death, sickness, and immiseration in its wake. And we hope to move beyond four years shaped by a regime that has cultivated and been buoyed by the most corrosive and contemptible forces in our politics.

To be clear, the hopes this new year bears are anxious, attenuated hopes. The red-letter date isn’t New Year’s, with its festivities celebrating a fresh start, nor Martin Luther King Day, with its conviction that moral courage and mass movement shall bend the universe’s arc. It’s not even Inauguration Day, with its long-anticipated installation of new leadership and all that that change augurs. The most apt metaphor the calendar offers up for this moment is Groundhog Day: a time to tentatively peek out of the burrows in which we’ve hunkered overlong, to stretch haunches cramped from defensive crouching, and to survey eagerly for harbingers that this extended winter might someday yield to thaw.

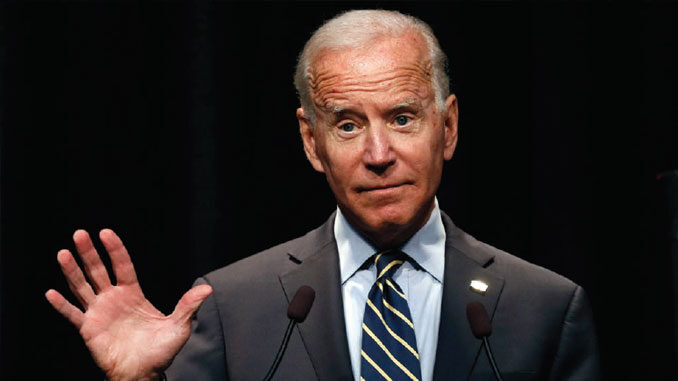

In considering what this moment means for the labor movement, though, we oughtn’t gloss over Inauguration Day entirely. We now have in office one who pledged to be “the most pro-union president you’ve ever seen.” That vow was not merely an isolated throw-away amongst a slew of campaign pitches. President Biden has repeatedly described himself as “a union guy,” and, after his election, flatly asserted “unions are going to have increased power” under his administration. How might his presidency measure up to such commitments?

As encouraging as it is to have in office an executive who unembarrassedly embraced the cause of organized labor, we must recognize that the measure of “the most pro-union president you’ve ever seen” is a laughably low hurdle to clear. None of the prior presidents of my lifetime — from Nixon on — showed evidence of vying very hard for that distinction. As labor’s numbers and political clout have waned over the decades, one party has come to take labor support as a given, necessitating neither courtship nor commitment, while the other has grown more nakedly hostile to the needs of workers vis-à-vis those of capital.

Make no mistake: for all the ersatz concern he voiced for working folks — “I will always put American workers first, always,” he boasted — Trump proved faithful to his party’s priorities, always putting the desires of billionaires before the needs of workers. From rolling back eligibility for overtime, to pledging to veto an increased minimum wage, to arguing against legal protections for LGBTQ workers, to gutting workplace safety regulations in the face of a pandemic, to scrapping programs to address racial bias on the job, to installing enemies of collective bargaining on the federal agency intended to protect workers’ right to organize — the ways in which the Trump administration has sought to undercut employees’ clout in their work-places have been too numerous to count.

It’s a hallmark of the terrible, tragic paradoxes shaping our cultural and political life that a lot of white working people proved so eager to accept as their champion this charlatan of a would-be authoritarian who built his brand by playing a cartoonishly belligerent boss on TV. In 2004, he crossed an IATSE picket line to perform that role on “The Apprentice.” But you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows, and you shouldn’t need an organizer to tell you on which side of a picket line Trump will be found.

After years of the previous administration’s war on workers, even complete neglect of our issues would represent significant progress. But the labor platform on which Biden ran was actually really good. Biden promised not simply to undo the damage recently done by Trump, but to reverse anti-union labor law dating back to the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. His agenda includes increasing the minimum wage, fighting wage theft, penalizing union-busting, expanding overtime guarantees under the Fair Labor Standards Act, correcting the misclassification of employees as independent contractors, ending corporate shell games that permit companies to duck their obligations to their workers, strengthening the right to strike, extending fundamental rights to agricultural and domestic workers, and promoting union organizing. It’s an ambitious array. Much of the agenda Biden announced during his campaign, it needs to be said, was predicated upon his anticipated ability to corral Congressional action. But his party was able to eke out only very tenuous control of the Senate; it remains to be seen whether that will be sufficient to push through bold new legislative action. The Protect the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which passed the House last year but which Mitch McConnell stymied in the Senate, would prove, were it enacted, the most dramatic overhaul of labor law since Taft-Hartley. Biden’s campaign platform backs the PRO Act, but its passage in the Senate as currently constituted is by no means a sure thing.

There may be no easy path to big legislative wins, but significant portions of Biden’s labor agenda might be achieved through executive action. Much of the damage effected by Trump, to the interests of workers and otherwise, was done through rule-making and executive orders, and might be undone via the same mechanisms. Indeed, the initial days of the Biden administration have been marked by a barrage of executive action resulting in many reversals of his predecessor’s policies.

One dramatic and welcome move Biden took on his first day in office was to fire Peter Robb, whom Trump had appointed to the position of General Counsel for the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). The NLRB’s General Counsel wields great power to decide how labor law is implemented, and Robb — a union-busting management-side lawyer who’d had a hand in Reagan’s notorious crackdown on striking air traffic controllers in 1981 — had been installed by Trump to undermine the NLRB from within. On his watch, the NLRB instituted a raft of policies running directly contrary to the agency’s legislative mandate to promote collective bargaining.

Robb’s term in office had not been set to expire until November, and he is the first NLRB General Counsel to have been actually fired by a president. (In 1950, President Truman asked for and received the resignation of the NLRB’s then-General Counsel, but Robb refused such a request from Biden.) Because the NLRB is an independent agency, some of Robb’s allies question the legality of Biden’s move, although a Supreme Court case from just last year (upholding Trump’s firing the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau) provides precedent for Robb’s removal. Axing Robb was widely regarded as a bold and controversial action, and quickly drew the ire of labor’s enemies. “The firing of Peter Robb belies all the [President’s] happy talk about unifying the country.”

Indeed, Biden’s appetite for conflict is a significant unknown for which we must solve. There has, in fact, been plenty of “happy talk,” as the WSJ opinion-writers would have it. In November, in virtually the same breath in which he promised “unions are going to have increased power,” Biden reassured his audience, “It’s not anti-business.” His was a candidacy defined by appeals to comity and civility, and a famous 2019 assurance to well-heeled donors that “nothing would fundamentally change” under his watch. After the Electoral College affirmed his victory, he reiterated an interest in transcending partisanship: “I will work just as hard for those of you who didn’t vote for me as I will for those who did.” And in his inaugural address, he earnestly declared, “my whole soul is in this: Bringing America together. Uniting our people. And uniting our nation.”

Those aren’t fighting words, and Biden’s commitments to the union members who helped elect him can’t be honored without a fight. Which president will we get? The self-professed “union guy” who knows which side he’s on and is gunning for organized labor’s enemies from day one? Or one who retreats back to his hole upon seeing his shadow?

Biden’s early days offer hope that he may prove a more reliable ally to labor than his old boss, President Obama. As a candidate in 2007, Obama had famously pledged that, if workers’ rights came under attack, “I’ll put on a comfortable pair of shoes myself. I’ll walk on that picket line with you, as president of the United States of America.” But Obama didn’t, in fact, make an appearance on any picket lines in Wisconsin when Governor Walker rolled back collective bargaining rights. Nor did he expend political capital attempting to reform labor law. Perhaps the “comfortable shoes” reference ought to have been a tell, because — although appropriate footwear is indeed important on the picket line — standing up to fight for what’s right is never comfortable.

We’ll need to watch how Biden acts in these early days of his presidency to gauge his commitment to the union values which he’s professed. But unlike the groundhog, our role is not simply to look for signs and to make predictions about weather we cannot control. To borrow a metaphor from King, labor’s role is to be not thermometer, but thermostat. If Biden shows himself to be too cool to the confrontation requisite to follow through on his commitment, it’s on us to turn up the heat.

To the degree to which a politician who had long fashioned himself as a moderate — who ran as a palatable and even milquetoast alternative to a continued reign of chaos — might govern as a bold reformer, credit is due perhaps not so much to the man as to the mass movements that impel him to action. Ultimately, that’s the logic that informs any grassroots, democratic struggle for justice: power isn’t so much about who you have in office; it’s about who you have in the streets.

I was in the streets last November, on the Saturday that Pennsylvania finally counted enough Philadelphian ballots for the race to be called for Biden. Trump and his toadies were already spreading slander to discredit the popular verdict against his presidency, already testing improbable and outrageous schemes to cling to power in the face of defeat. In response to these clumsy machinations, a handful of labor and community groups around L.A. called for an emergency rally downtown. The teachers’ union printed placards that exhorted, “Defend Each Other, Demand Democracy,” and thousands of us poured into the streets for a peaceful demonstration to insist that we would not be disenfranchised by this coup that couldn’t shoot straight.

I personally have been pretty scrupulous throughout the pandemic about maintaining appropriate distancing, so November’s mass action was the first time since the enormous Black Lives Matter protests last summer that I had found myself in a crowd of that size. It was exhilarating and a little uneasy, at first, being immersed in such a mass of bodies, the proximity of so many strangers after so many months of virtual hermitage. As we marched and chanted — “¡El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido!” and “Whose streets? Our streets!” — waves of emotion washed over the throng — outrage, relief, hope, and triumph.

We were grieving the bodies ravaged by a virus and grieving the damage done by a would-be strongman and his enablers to our body politic. We were celebrating the hard-won prospect of recovery. And we were defying an array of clowns and bullies who believed America was greater when people like us — a motley multitude of working folks of all races, ethnicities, and genders — knew our proper place.

With masked mouths and swelling hearts, we chanted and marched through the streets of Los Angeles. Someone in the crowd produced a trumpet and began to blow, a drummer materialized, and suddenly, exuberantly, our marching morphed into ecstatic dancing.

In that brief and delirious spell of public jubilation, our revelry certainly wasn’t about Biden. It wasn’t even really about Trump. It was about us, about our claiming these streets, our commandeering them for a dance floor. We’d been waiting years for this party. We collectively decided we would let the sun shine on us and cast our shadows where it might, and we’d let nobody tell us to get back. At a time when our leaders and our institutions had shown themselves to be all too fallible, we were out there to appropriate space for our shared joy and to demonstrate to one another that we had each other’s backs. Maybe that could be enough.