by Betsy A. McLane

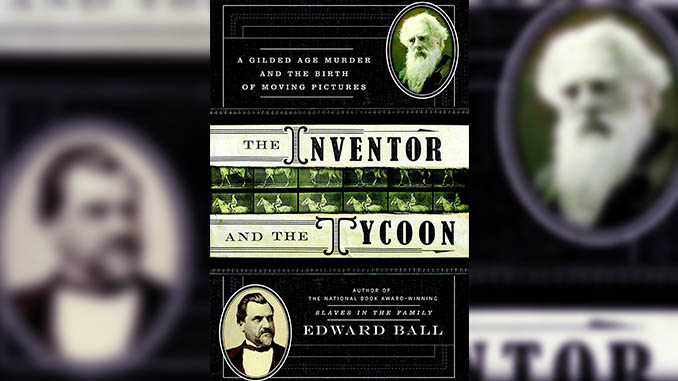

The Inventor and the Tycoon:

A Gilded Age Murder and the Birth of the Motion Picture

by Edward Ball

Doubleday

Hardcover, 464 pps., $29.95 ISBN-10: 0385525753

A select handful of names are forever linked to the invention of motion pictures: Thomas Edison (US), August and Louis Lumière (France), Robert William Paul (UK) and Eadweard Muybridge (UK and US). Each of these and others can lay claim to being the man who came up with the idea of the “movies.”

In The Inventor and the Tycoon: A Gilded Age Murder and the Birth of the Motion Picture, a work of nonfiction that reads like a historical novel, author Edward Ball makes a strong bid for the importance of still photographer Muybridge (1930-1904). “The photography with which Muybridge shot animals and people performing these daily tasks, and his projection of these on screens, was the genetic imprint of all visual media.” He bases this claim on the fact that Muybridge’s “motion studies” first shot in 1887-88 were all shots of action, strung together to create the illusion of movement, and that they were sometimes projected.

Ball overstates this theme. Personally, I place Muybridge in the important pre-cinema category and find Edison’s invention of flexible celluloid film stock as a key turning point. Most historians agree that the signal event took place in Paris in 1895 when the Lumière brothers publically projected images shot by a sprocket- driven camera that was designed specifically to use celluloid strips. The same machine also served as the projector. Even so, no one doubts Muybridge’s place among the pantheon of men whose work led to the modern moving image.

In some ways, Muybridge might be described as the first to project edited photographs, since his invention relied on individual shots strung together in a particular order and then projected. Unlike the Lumières, each image was captured by an individual camera, so any sense of editing was created from machine to machine rather than from shot to shot. These now-famous images of horses and athletes going through their paces were first seen by invited elites in the opulent Victorian parlor of former California Governor Leland Stanford (1824-1893). Similar devices would have been familiar to the guests who had almost certainly seen the zoetrope, the praxinoscope and other similar entertainments. The development of pre-cinema, like that of all film, relied on the combined efforts of many people.

None of the book’s characters elicits much sympathy.

For instance, as early as 1832, Simon Ritter von Stampfer created the stroboscope that displayed images spinning on a disc viewed through slits in a second disc, providing a fast enough rate to simulate a couple seconds worth of motion. A primitive kind of slide projector, the magic lantern existed in Rome since the mid-1600s. In 1853, these two inventions were combined by Franz von Uchatius, who used a magic lantern to cast hand- drawn stroboscopic images onto a wall. Using polygraphs, sphygmographs, dromographs and other myographs, Étienne-Jules Marey succeeded in analyzing diagrammatically the walk of man and of horse, and the flight of birds and insects. The results, published in La Machine Animale in 1873, inspired Stanford and Muybridge.

A second theme of The Inventor and the Tycoon is the odd friendship between two opposite icons of pioneer-era California: Muybridge and Stanford. Conventional film history has it that Stanford placed a bet to prove his belief that all four horses’ hooves left the ground at some point during a trot and a gallop. The trot was important because of its slowness and Stanford’s obsession with racing horses, especially sulky racing. This proof was made possible because of Muybridge’s inventiveness, setting up a series of still cameras with trip wires that captured the horse as it ran, and by Stanford’s typically lavish spending on the project.

Ball dismisses the betting part of the story based on his deduction that the pompous Stanford was never a gambling man. The author relies on many such assumptions about the lives of Stanford and especially Muybridge, since very little recorded history exists about this peripatetic and somewhat mysterious man. The author also presumes that Muybridge was obsessed with motion, partly because many of his groundbreaking 1868 large-format photographic landscapes of Yosemite featured rushing waters. Ball even goes so far as to suggest that the arrival of the first locomotive in Muybridge’s (then Muggeridge) hometown near London was the youthful inspiration for his fascination with movement.

Filling in history with many such assumptions about the inner minds of his characters, Ball has produced a carefully researched account of the unlikely intersection of the lives of many kinds of people who rushed west seeking their fortunes. The book is meticulously footnoted with facts supporting the nature of life in late 19th-century California. It tells a compelling story that has only been hinted at in previous books, not only the friendship of Stanford and Muybridge, but the headline news of the murder committed by Muybridge.

The development of pre-cinema, like that of all film, relied on the combined efforts of many people.

The convoluted plot of The Inventor and the Tycoon is true, and Ball’s psychological projections are perhaps necessary for today’s readers to engage in the tale. The drama plays out against the backdrop of San Francisco’s rise as the economic and cultural capital of the West. Detailed descriptions of California’s gold and silver booms, the decimation of the continent’s last free-roaming Indian tribes, and the grandiose and brutal building of the Transcontinental Railroad by tycoon Stanford and his cronies are background for this peculiar saga. Another theme is Muybridge’s constant reinvention of his persona, which extends even to changing his name several times. Ball repeatedly remarks on the ways that people, then and now, are drawn to California to shed their pasts and start new lives.

The narrative begins and titillates throughout with Muybridge’s melodramatic murder in 1874 of his young wife Flora’s lover, the rakish Harry Larkyns. None of the book’s characters elicits much sympathy. Ball’s thoroughly footnoted fact-finding and his attempts to flesh out their thoughts and feelings somehow make these personalities more distant. It is not a spoiler to note that Muybridge was acquitted by a defense of insanity — allegedly caused by a fall in a stagecoach wreck — and more importantly by the frontier philosophy that a husband had every right — and the moral obligation — to avenge himself on his wife’s despoiler.

Ball arranges the book into shorter pieces set within chapters, and there is much in it to relish. His account of many facets of California history, about how the legends of the Golden State came to be accepted as fact, is astute. But the reiteration of facts in these vignettes becomes tedious, as if the author does not trust the reader to remember things from one chapter to another. The many well-reproduced photographs offer noteworthy insight into the natural magnificence, townscapes, places and faces of the era. Muybridge’s wet-plate scenics of Yosemite still elicit awe and wonder at how the photographer achieved such art. The formal studio portraits of the time, which Muybridge largely refused to make, reveal how the constrained Victorian values of class and culture must have clashed with the last roughneck vestiges of America’s Wild West.

The Inventor and the Tycoon is an engrossing book that could have been made sleeker and more significant (as could many creative works) if it had been placed in the hands of a good editor.