By Peter Tonguette

When picture editor Affonso Gonçalves, ACE, signed on to make “The Lost Daughter,” he wound up with a most interesting collaborator. Acclaimed as an actress for her work in films such as “Secretary” (2002), “Sherrybaby” (2006), and “Crazy Heart” (2009), Maggie Gyllenhaal had never directed a film before. But she chose to turn Elena Ferrante’s novel “The Lost Daughter” into her feature directing debut.

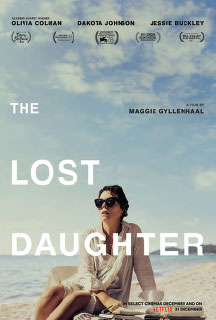

Released by Netflix in theaters on Dec. 17 and available to stream as of Dec. 31, the intricately edited film invites viewers into the mind of high-minded middle-aged professor Leda Caruso (Olivia Colman) who, during an otherwise uneventful vacation in Greece, has a run-in with a rowdy, rather unrefined family from America, including young mother Nina (Dakota Johnson). Prompted by a series of encounters with Nina and her small daughter, Leda is inundated with memories of her own past as a young parent managing work obligations while raising two daughters. In a film that effortlessly and intuitively melds past and present, Leda is played in flashback by Jessie Buckley. The film co-stars Peter Sarsgaard, Ed Harris, and Paul Mescal.

By the time cameras finally rolled in September 2020, however, “The Lost Daughter” was no longer Gyllenhaal’s debut film, and Gonçalves was no longer a first-time collaborator. During the long run-up to shooting “The Lost Daughter,” Gyllenhaal was tapped to make a short film for an anthology series released by Netflix, “Homemade.” She asked Gonçalves—patiently waiting in the wings to start work on “The Lost Daughter”—to cut her short film, “Penelope,” which turned out to be her directorial debut.

“She sent me the script and said, ‘I’m doing this—do you want to do this? We can work together first,’” Gonçalves said. “I said, ‘Absolutely.’”

Not only did Gyllenhaal get her directorial feet wet, but she found herself validated in her decision to hire Gonçalves to cut “The Lost Daughter.” Although the two worked remotely on “Penelope”—Gyllenhaal was in Vermont, where her film was shot, while Gonçalves was in his home base in Los Angeles—they realized that they saw movies and moviemaking the same way.

“It was like we got to experiment and see: Do we really understand each other? And what I realized right away was we do,” Gyllenhaal said. “Of course, I’ve worked with people in my life—not ever an editor, before this—who didn’t understand me, and it’s really hard. Instead, I think we hit something really unusual and special. We could read each other’s minds in the way the dearest friends can.”

By the time Gonçalves and Gyllenhaal sat down to work on “The Lost Daughter,” then, the two were already veteran collaborators of a sort. “It was super-smooth, and it just confirmed the feeling that I had that I really wanted to work with her,” Gonçalves said. “I can say that I worked with her on her very first film she directed, and the second film. She wasn’t a first-time director at that point.”

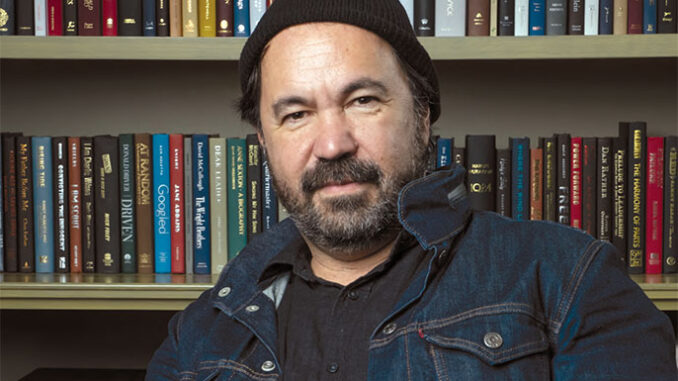

A native of Brazil, Gonçalves has, during the past quarter-century, accumulated a long list of impressive credits in independent film and beyond. His best-known films include Debra Granik’s “Winter’s Bone” (2010), Benh Zeitlin’s “Beasts of the Southern Wild” (2012), and multiple projects for Jim Jarmusch, including “Only Lovers Left Alive” (2013), and Todd Haynes, including his latest documentary, “The Velvet Underground.” When his name was proposed as a possible editor on “The Lost Daughter,” Gyllenhaal jumped at the chance.

A native of Brazil, Gonçalves has, during the past quarter-century, accumulated a long list of impressive credits in independent film and beyond. His best-known films include Debra Granik’s “Winter’s Bone” (2010), Benh Zeitlin’s “Beasts of the Southern Wild” (2012), and multiple projects for Jim Jarmusch, including “Only Lovers Left Alive” (2013), and Todd Haynes, including his latest documentary, “The Velvet Underground.” When his name was proposed as a possible editor on “The Lost Daughter,” Gyllenhaal jumped at the chance.

“Someone had told me he was a great editor, and then I realized I’d seen many of his films,” Gyllenhaal said. “There’s something alive and buoyant about his work. It’s not plodding; it’s confident. It’s not one foot in front of the other. It’s got a different kind of emotional logic, which I found really compelling.”

For his part, Gonçalves was drawn to “The Lost Daughter” not only on the strength of the script but his discussions with Gyllenhaal about the project and her approach to filmmaking. “Immediately, I was really taken by the ideas she had for the film and all the plans she had for making this movie,” Gonçalves said. “I really wanted to be involved.”

While watching dailies in his cutting room in New York, Gonçalves could tell that the footage was not only strong but redolent with editorial possibilities. “It wasn’t like I came in with preconceived ideas of, ‘This is exactly how I’m going to do it,’ but once we started watching the footage, it was like, ‘OK, I think I got it,’” Gonçalves said. “I had a sense that I could experiment, [especially] with the transitions between the [present] Olivia world and the [past] Jessie Buckley world. . . . It is free in the sense of how you work with coverage. I play with the sound sometimes, not syncing with the image, and there are some jump cuts.” He added: “I knew that I could apply that to the flashbacks.”

When production wrapped last autumn, Gyllenhaal returned to New York where Gonçalves had been preparing a first pass during the shooting. “She needed to quarantine a little bit before she came in,” Gonçalves said. “It came time for me to finish, do another pass, and then she came to the cutting room. And then we started working together.”

After Gyllenhaal viewed the assembly, the two went back to the beginning and proceeded one scene at a time. Some elements—including an opening sequence that took place prior to Leda’s vacation—were dropped almost immediately. “I came back not with the movie cut in my head—I don’t really know what that means,” Gyllenhaal said. “But I did come back with a real sense of my way through each scene. And I was holding it all in my arms—all of it: these performances, these ideas, and sort of the movement through the story.”

Unlike their first collaboration, which took place virtually and by phone, Gyllenhaal was a fixture in the cutting room on “The Lost Daughter.” The possibility of cutting remotely was discussed, but ultimately Gyllenhaal felt strongly that she needed to be present for the editing of her first feature. And that was fine with her editor. “I usually prefer the director being with me as much as possible because I like the dialogue,” Gonçalves said. “Sometimes when I’m cutting, I’m sort of narrating what I’m doing or what I’m thinking, and then she can be involved. She came every day, and it was really nice.”

‘I USUALLY PREFER THE DIRECTOR BEING WITH ME AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE BECAUSE I LIKE THE DIALOGUE.’

Although Gyllenhaal had indicated the placement of Leda’s flashbacks in the screenplay, and this roadmap was mostly followed during postproduction, Gonçalves had a free hand in playing with the structure—namely, which flashbacks fell where. “Part of it was planned, obviously, but there was so much that, in the cutting room, it would be like: ‘OK, when do we see the little girls dancing and their parents laughing?’” he said. “That was very freeing—we were just experimenting.”

That ethic of experimentation included one of the film’s most quietly memorable passages: At one point, Lyle (Ed Harris), who oversees the house where Leda is staying, arrives bearing octopus to prepare for an early diner. As written and shot, Lyle fries up the octopus, and when the meal is served, the two have a long talk. But, despite the strength of the writing and acting, when Gyllenhaal watched the scenes with Gonçalves, she felt they just didn’t play. “We were like, ‘They don’t work; they’re not lifting off,’” said Gyllenhaal, who, during the course of the postproduction process, had been watching or rewatching many classic films, some on her own initiative, others on the advice of Gonçalves or assistant editor Ron Dulin. (“I would come in in the morning and they would be talking about ‘The Tenant,’ the Polanski movie,” Gyllenhaal said. “I was like, ‘What’s ‘The Tenant’? Then I’d go home and watch it and [think], ‘How did I never see this movie?’”)

In figuring out how to preserve elements of the octopus scenes, Gyllenhaal drew upon another recent viewing: Nicolas Roeg’s much-admired thriller “Don’t Look Now” (1973), which, in a famous sequence, intercut a sex scene with stars Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie with footage of the two actors subsequently getting dressed up for a night out. The way the scene ignored the boundaries of chronological time suggested a possible approach for the octopus scenes in “The Lost Daughter.” “I had just watched ‘Don’t Look Now,’ not for the first time, but for the first time in many, many years at [Gonçalves’s] suggestion,” she said. “I said, ‘Why don’t you cut it like the sex scene in ‘Don’t Look Now’? [Gonçalves] said, ‘Give me half an hour.’”

The resulting scene mixes shots of Lyle frying the octopus with fragments from Lyle and Leda’s subsequent conversation during the meal; the decision to merge two scenes into one not only preserved the writing and acting in the scenes, but gave the material an unexpected dreamlike ambience. “It was very satisfying to be able to do that,” Gonçalves said. “It’s odd how much it worked—the dialogue between one scene and the other—but it was never meant to be cut that way.”

Also unplanned was the film’s final running time of just over two hours. Although “The Lost Daughter” takes its time to reach its destination, neither director nor editor had a set length in mind when cutting began. “We just naturally cut down, cut down, cut down until we found, ‘OK, this is the ideal time,’” Gonçalves said. “It’s not a fast-paced movie by any stretch of the imagination. We screened the film for a very small amount of people, and there was some feedback, sort of arbitrarily people saying, ‘Just cut 15 minutes.’ It’s like, ‘OK, great—what 15 minutes?’” The leisurely, unhurried pace allowed more time for the audience to get to know, and enter the consciousness of, Leda. “[This] was the appropriate time to spend with the characters and to tell the story,” Gonçalves said.

‘I’M SO HAPPY THAT PEOPLE ARE REACTING AND UNDERSTANDING THE FILM.’

In this, as in so many other things, Gyllenhaal trusted the judgment of the editor who was, by then, not merely an editor to help guide her feature debut but a trusted partner in the postproduction process. “I said, ‘I don’t want to make a long movie,’” Gyllenhaal said. “He said, ‘All right—well, let’s just make the right-length movie.’ Obviously, there’s going to be a point at which it’s no longer compelling, and we don’t want that. But it doesn’t matter what the number is, and he was very clear about that with me from the very beginning.”

Gonçalves reflects on the experience, and the final product, with pride. “I’m so happy that people are reacting and understanding the film,” he said. “I couldn’t be more grateful.”