by Edward Landler

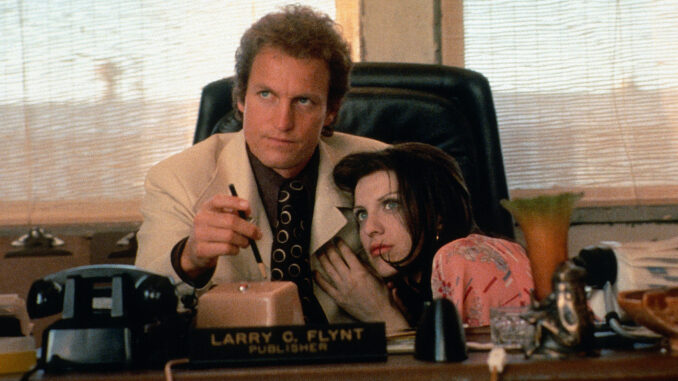

Director Miloš Forman’s The People vs. Larry Flynt premiered 20 years ago, on October 13, 1996, the closing night of the New York Film Festival. From an original screenplay by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, it traces the life of the Hustler publisher from selling moonshine in Kentucky at the age of 12 through his creation of one of the raunchiest and most popular American sex magazines to his landmark First Amendment victory at the United States Supreme Court.

The film met with both acclaim and disdain. In an Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Oral History interview, Marcia Nasatir, an industry executive involved with the film, said, “Miloš found the worst person in the world to defend. When I talked to women outside the business, they said, ‘I’d never see a movie called The People vs. Larry Flynt.’”

Far from celebrating sexual liberation, Hustler’s images of women were often demeaning and sometimes violent. Yet, in depicting the unseemly Flynt and his wife, stripper Althea Leasure, the film distills and blends raucous comedy and personal tragedy to draw a sharp satiric bead on the contradictions of the American character.

The day after the premiere, the porn tycoon flew Forman and his stars in his private jet to the director’s native land, the Czech Republic — a free democracy since the fall of Communism in 1989. At the invitation of President Václav Havel (a playwright and the filmmaker’s friend from childhood), Flynt’s saga was presented to an audience of 200 at the Presidential Palace in Prague with an interpreter providing simultaneous translation off-screen.

Nasatir commented, “You’ve got to live in a country where you have no freedoms to appreciate what it is.”

Three years before, while director Tim Burton was still shooting Alexander and Karaszewski’s script for Ed Wood (1994), about one of cinema’s cheesiest creators, the writers were drawn to another less than fully admirable real-life figure. “Just two regular Joes with wives and kids,” as they said in their introduction to the published screenplay, they wanted to write about “a man most noted for his shameless vulgarity.”

When they pitched the project to Columbia Pictures, they also sent an outline to Oliver Stone. His flair for mixing popular culture with political controversy in movies like Born on the Fourth of July (1989), The Doors (1991) and JFK (1991) made him an obvious choice to direct.

The Columbia executives told them, “It’s a Capra movie with porn!” When Stone expressed interest, Janet Yang, his partner in the production company, Ixtlan, set up a development deal with the studio.

Drawing from major news sources, court transcripts of Flynt’s legal battles and interviews with the publisher’s associates and friends, the writers spent half of 1994 writing a 215-page draft. When the script was cut down to 167 pages, Stone realized he was still too busy with Nixon (1995) to direct — but he wanted Ixtlan to produce.

Its “freedom of expression” theme led him to send the script to Forman, who had grown up under both Nazi and Communist dictatorships. A leading figure in Czech cinema, he had infused such films as Loves of a Blonde (1965) and The Fireman’s Ball (1967) with sly satire too subtle for ham-fisted government censors to comprehend.

The director was able to leave what was then Czechoslovakia during the “Prague Spring” of 1968 to seek work in America, and did not return after Soviet troops crushed Alexander Dubček’s reformist regime. Since then, Forman had made six English-language movies, two of which — One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and Amadeus (1984) — had brought him Best Picture and Best Director Oscars.

When Forman received the screenplay, he saw Flynt’s name in the title and threw it aside. When his manager told him Stone had sent it, he read it and found, as he said in an interview shortly before the film’s premiere, “the kind of script directors dream about.” He committed to the project in March 1995.

Forman said, “I had experienced political regimes in which crusades against pornographers…turned into the worst censorship where freedom of the press was practically eliminated entirely. It started with homosexuals and pornographers, and Jews and blacks, and finally…your plumber is a pervert…and you are a pervert.”

Cutting the final script down to 140 pages, Forman said he and the writers agreed that “the hero would be the Supreme Court and everybody else would be simply human with all their pros and cons.” The director, however, was determined not to glamorize pornography “because I am conditioned from my childhood to see pornography as bad and I still feel that way… I could have splashed the screen with images from Hustler that would make people scream in disgust.”

Such images were only suggested off-screen or not seen clearly in frames composed to draw attention to characters’ reactions to them. A graphic exception was a picture of a woman’s naked body being put through a meat grinder.

They also went through the script thoroughly with Flynt himself. He was no longer the wild man of the 1980s who drew contempt citations and was confined to a psychiatric prison facility for throwing oranges and spitting at the federal judge whose orders he defied. The writers regarded him as “a charming, soft-spoken man” — still in a wheelchair due to the 1978 sniper’s attack that severed his spinal cord.

As they completed their revisions with the publisher, Forman recalled, “I mustered up my courage and asked, ‘Larry, don’t you mind that you do not really look like a hero in some of these scenes?’ Flynt grunted, ‘Yes, I do mind, but what can I do about it when it’s true?’”

In December 1995, Columbia joined with Mike Medavoy’s Phoenix Pictures to finance the movie. Michael Hausman, who had worked on four of Forman’s films, would produce along with Stone and Yang.

Meanwhile, Forman had assembled a mix of experienced actors and non-professionals with fitting backgrounds to heighten the movie’s sense of reality, confirming Phoenix executive Nasatir’s view that “Miloš is one of the great casting people in the world.”

The director was set on Woody Harrelson to play Flynt “from the moment I met the guy.” The Texas-born Harrelson acknowledged, “Poor white trash, that’s me all the way.” Appropriately, Harrelson’s younger brother Brett was cast as Flynt’s brother Jimmy. Determined to work with Forman, Edward Norton pursued the role of civil liberties attorney Alan Isaacman so earnestly that he was a natural choice.

Political strategist James Carville played an anti-porn prosecutor and WNYW-TV news reporter and anchor Donna Hanover (and wife of then New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani) played evangelist Ruth Carter Stapleton (sister of Jimmy Carter). Lawyers played lawyers and US marshals played themselves, as did Flynt’s personal bodyguard and personal physician. Flynt himself took on the role of the judge presiding over his first obscenity trial in Cincinnati.

The most problematic casting choice was rock singer Courtney Love, brought in by casting director Francine Maisler, to play the part of Althea Leasure Flynt. Not yet two years since Love’s husband, Kurt Cobain of the band Nirvana, committed suicide, her own life had been nearly as troubled and indulgent as Leasure’s.

Forman offered her the role only if she would stay off drugs and agree to regular drug testing, but the insurance company refused to cover her. Yang negotiated a separate non-refundable $750,000 insurance policy. Columbia and Medavoy refused to pay for it and the cost was split among Stone, Yang, Hausman, Forman, Harrelson and Love.

Flynt told Premiere magazine that what got the singer through production “was having the good fortune of having Miloš Forman as a director and getting involved with Edward Norton during the filming.” More than that, Love fully committed to the part and provided a real emotional grounding to a complex human being.

Early in the shoot, she captured respect in key scenes with Harrelson. At the American Cinema Editors’ EditFest New York in 2012, the film’s editor, Christopher Tellefsen, ACE, said, “Almost every scene with them was done with two cameras because she was such a good improviser… She would take Woody by surprise so often that it…created a wonderful dynamic.”

With a cast and crew of over 150, the 75-day shoot ran from January 17 to April 27, 1996. Shot by Philippe Rousselot, ASC — an Oscar winner for Robert Redford’s A River Runs Through It (1992) — most of the principal photography took place in and around Memphis, Tennessee, standing in for Kentucky, Ohio and Georgia. The Memphis train terminal built in 1929 was converted into a full-sized replica of the US Supreme Court chambers where Flynt’s Jerry Falwell lawsuit was ultimately decided.

Despite filming in the Bible Belt, the production attracted little attention. A Memphis TV news crew covered the shoot on a day of exteriors depicting Flynt being met by protesters as he arrived for his Cincinnati trial. Thinking the protest real, the local TV station ran their crew’s footage as showing a real demonstration against the making of the movie.

Late in March, production moved briefly to Oxford, Mississippi, to shoot another old courthouse exterior and, during most of April, major sequences were shot at the Flynt Publications building on the Sunset Strip and at Flynt’s mansion in Bel Air. The final day of filming took place on the steps of the Supreme Court building in Washington, DC.

The major difficulty facing editor Tellefsen was the amount of footage. Cutting dailies of a scene during the shoot, he said, “I did a few versions of it and [Forman] says, ‘That’s good…but try four versions…no, make 10 versions.’ It was fun but a lot of work.” He continued: “Miloš doesn’t move the camera much, but everything was covered. In the trial scenes, every single juror had coverage. There was about 800,000 feet of film… It was a big, challenging job.”

Wishing the controversy would go away, Columbia gave no tickets to Larry Flynt for the Oscars ceremony on February 28, but Woody Harrelson took him as his guest.

The first cut was three hours long and the final 129-minute cut was locked in September, barely a month before the New York premiere. The National Organization of Women had issued a statement attacking the yet-unseen film back in May, but the end of 1996 saw Larry Flynt on about 50 Top Ten lists.

On January 7, 1997, The New York Times ran an article by Gloria Steinem claiming the movie glorified Flynt and was “even more cynical than the man” because it didn’t own up to Hustler’s sexism. Following up, she placed a full-page ad in Variety on January 17, paid for by Ralph Nader, to influence the film’s Academy Awards chances. It received just two nominations — for Forman’s direction and Harrelson’s performance.

Wishing the controversy would go away, Columbia gave no tickets to Flynt for the Oscars ceremony on February 28, but Harrelson took him as his guest. Neither the actor nor the director won, but earlier in the month The People vs. Larry Flynt won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival and Forman was honored with the Torch of Liberty Award by the American Civil Liberties Union. On its initial run, the movie made $20 million, barely covering its advertising budget. The studio wrote off the $36 million production costs as a loss.

In support of the film, writer/producer Naomi Foner (Running on Empty, 1988) wrote, “The movie did expose the inevitable results of multiple sex partners and drug abuse.” Perhaps understanding this himself, Flynt has said, “I will always hold myself responsible for Althea’s [AIDS-related] death.” The film’s moving final images weave these individual realities within the larger context of American society.

As Forman stated, “I don’t say you should like what Larry Flynt does, but I admire the fact that I live in a country where I can take Hustler and read it as well as throw it away. The fact that this is the freest country in the world doesn’t mean you can take it for granted, because we will never conquer the stupidity of fanatics and power-hungry megalomaniacs.”