By Laura Civiello

[Maurice Schell, a longtime Editors Guild member and sound editor who worked on major features such as “Casualties of War” and “Scarface,” died last month. Here he’s remembered by his wife Laura, who is also a sound editor and MPEG member. – ed.]

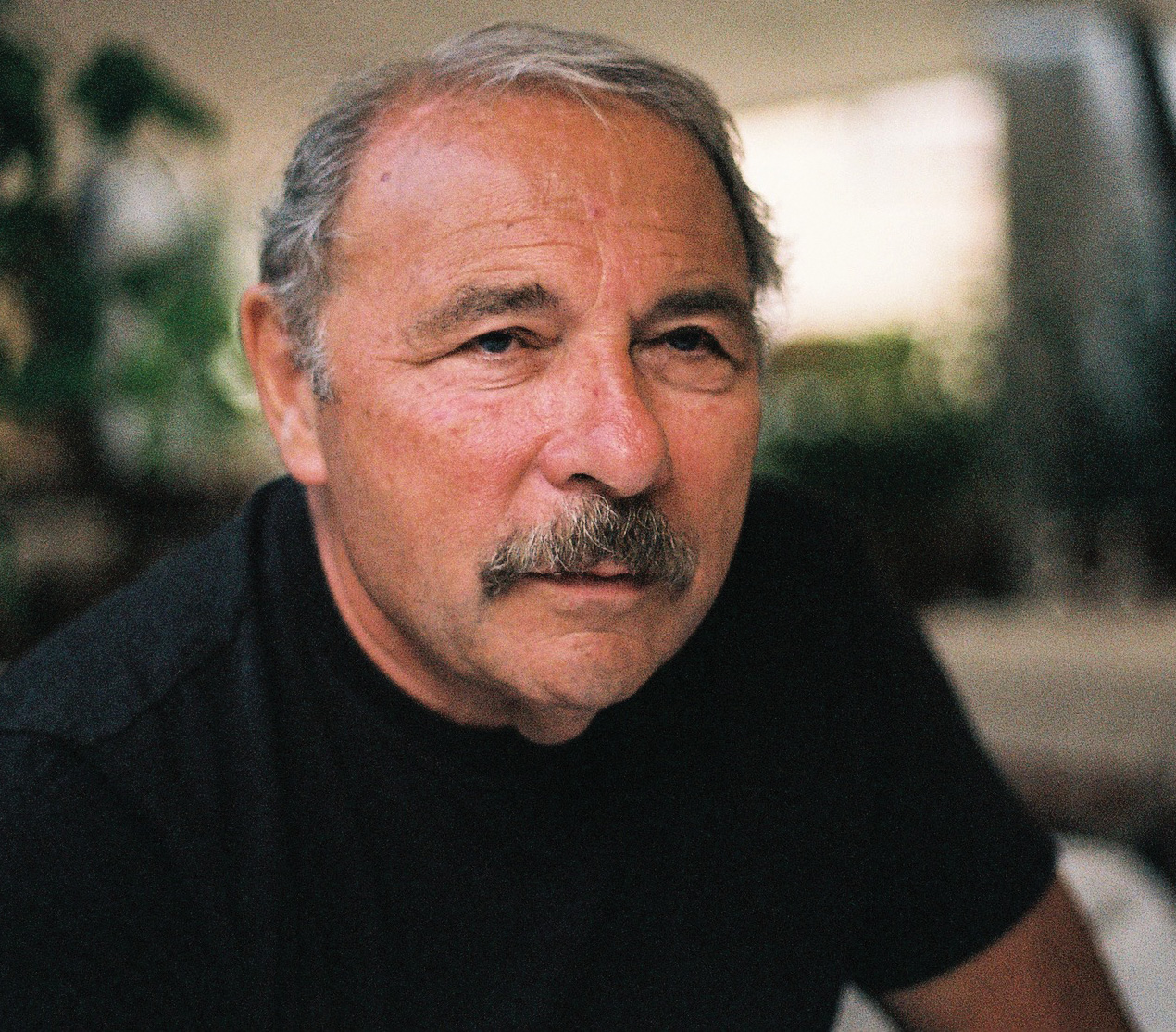

My husband, Maurice Schell, died peacefully on the evening of November 21st.

Maurice was born in Paris, France, on November 14th, 1937. His mother had emigrated from Poland and his father from Germany, both fleeing the rise in antisemitism in their native countries. The first four years of his life are well-documented in idyllic family photographs taken by Julius, his photographer uncle. They show happy young parents doting on their only child. The German occupation of Paris brought all that to an end. Joseph Schell ignored the ruling to register the family as Jewish and wear the yellow star. While hundreds of Parisian children in his Marais neighborhood of Paris were being deported to their deaths, Maurice was spirited off to the countryside on the back of a motorcycle late one night by Julius, who had connections to the French Resistance. He remembered standing at the foot of his mother’s bed and waving goodbye. She was at that point dying of cancer. He remained in the tiny town of Sancheville, under the care of an elderly woman, Madame Villetard, until the end of the war four years later. German troops were ever present due to a prisoner of war camp nearby. He vividly recalled the sounds of marching boots, of hiding under the bed as bombs fell, of witnessing the townspeople hiding an Allied paratrooper and burying his parachute late one night. The children knew not to utter a word.

His father survived the war by concealing his Jewish identity and working as a bookkeeper for a German munitions company. Officers as high up as Rommel would pass through. He would have to endure socializing with them as they ridiculed Jews. Although he was able to help the Resistance by procuring forged papers, towards the end of the war he was apprehended by them while en route to Paris to deposit company funds. As he was in possession of a car, a pistol, and a satchel of money, his protestations of actually being Jewish were not believed and he spent six months in jail until finally being cleared. He returned with Maurice to Paris where he later remarried and emigrated to New York in 1949.

Life in the New York multi-ethnic neighborhoods of Washington Heights and Inwood was a struggle. His father was able to purchase a modest luncheonette, where the family worked long hours. Maurice worked nearly full time from a young age to help out. His earnings went to the purchase of the first family car, although he wasn’t permitted to drive it. His father’s wartime experiences had left him emotionally shut down, and the parental affection that was showered upon him in his first four years was never to be repeated. Although he neglected his schoolwork, he excelled in sports and drawing, but when he was offered admission to a specialized arts high school, his father dismissed the idea. And later, when a Dodgers scout who spotted Maurice offered him a minor league tryout, his father’s reaction was “You’re going to play ball for a living?”

At the age of 20, when his father suffered a heart attack, Maurice took over running the luncheonette with his stepmother. Later, he worked for the Miles Shoe Company, traveling all over the country taking inventory in local stores. He witnessed separate water fountains in the South, and recounted a store manager boasting of the previous night’s revels harassing Blacks. It left a strong impression.

Around the same time he experienced a kind of cultural awakening. He spoke of going to see the Fellini film “La Strada” and staying to see it a second time. He had never seen a film like it and it affected him deeply. Another pivotal experience was a late night conversation with friends concerning the nature of work and the need to find something you loved doing. The next day he resigned from Miles Shoes. “Can’t you give us a few weeks’ notice?” they asked. “No, because then I may never leave.”

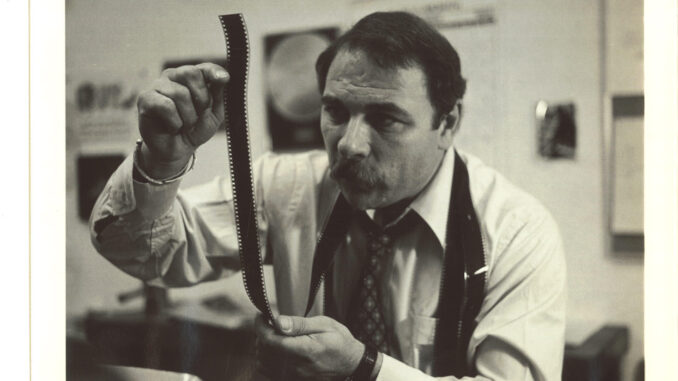

He started looking for jobs in film and was offered a day’s pay sweeping floors and moving equipment for the Maysles brothers, the famous documentarians. They kept him on, and an early mentor there was editor Charlotte Zwerin. Soon after he assisted picture editor Jerry Greenberg on “The French Connection.” He moved on to sound assisting for a number of years in all areas of sound editing – music, effects, ADR, dialogue. Eddie Beyer was another mentor. Once Maurice started editing, he quickly moved up to supervising sound jobs. Working with Bob Fosse on “All That Jazz” in 1979 was an early, inspirational experience.

A year later, Maurice was working as a sound editor on “Reds.” I had been working in TV commercials and was trying to break into features. “Reds” had a mammoth crew and I heard they were hiring from outside the feature community. I arranged to get an interview in the Sound Department. When I entered the elevator at Trans Audio and asked someone where the sound editing rooms were located, Maurice turned to look at me and said to a companion, with a bit of attitude, “I know where she’s going.” That felt rude. “Who’s the wise guy?” I thought. He was also conspicuously strolling back and forth as I was being interviewed.

Then I joined the crew as a sound apprentice and started getting to know him. I had been a film buff since childhood and had a book about film rebels on the shelf of my editing table. John Garfield was on the cover. Along with Brando, he was my favorite actor. Most of my contemporaries didn’t even know who he was. Maurice knew him – and loved him. We enjoyed talking film, and politics. I came of age in the 60’s and cared deeply about the issues of the day. Maurice was a teenager in the 50’s (picture a slimmer Maurice in jeans and a white t-shirt with a pack of cigarettes folded in the sleeve). He did not connect with hippies but he was passionately against all forms of bigotry and bullying, be it directed towards Jews, Blacks, women, gays or anyone else. He had experienced fascism firsthand and his antennae were up all the time.

“Reds” was a grueling job. Much of the sound crew was on for a year – the picture crew, two years – six to seven days a week, usually until 11:00 p.m. They provided lunch, preferred that you eat in. Everyone revered picture editor Dede Allen, but her insistence that we work those hours, in case “Warren” (Beatty) might need something, felt excessive to many of us. People were having nervous breakdowns, marriages were breaking up, there was a suicide attempt.

Maurice went into rebel mode. He taped a paper cup on the wall outside his cutting room door, dripped blue liquid from it down the wall, and put a sign “Jonestown” under it, after the cult that had committed suicide with poisoned Kool-Aid. My cutting room was directly opposite, and I remember Dede, on one of her rare visits to the Sound Department, freezing in front of it. I think were it not for the excellence of his work, Maurice would have been fired. There were many other antics. He was very funny but never malicious, and I respected his taking a stand against what he felt was an oppressive situation even if his career might have suffered as a result of his bad-boy behavior.

One weekend night, the crew was quitting at 9 and planning to attend a party somewhere. I was sitting in his cutting room, which had lovely artwork on the walls and carefully tended plants covering the window sills. This Inwood street guy had refined sensibilities. He stood hunched over his moviola. “I don’t want to go to a party,” I said. “Want to go to a movie, Maurice?” PAUSE. “Yeah, I’ll go to a movie.” From then on we were inseparable. When the job ended eight months later we vacationed in France. Upon our return I suggested we move in together.

Long, long pause.

“I’m not against it,” he said.

Maurice loved women. He thought they were the superior sex. When I got pregnant, he was hoping for a girl. He got his wish. Our daughter, Lea, was born on December 12th, 1984. He was determined to give her all the affection his father had withheld. They adored each other.

In the subsequent 30 years of sound supervising, he worked for directors Sidney Lumet, Brian DePalma, Milos Forman, Jan Kadar, Susan Seidelman, Bruce Beresford, Spike Lee, David Mamet, Paul Schrader, Robert Benton, Nina Rosenblum, Lasse Hallstrom, Rob Marshall, Antoine Fuqua, and many others. Adhering to the director’s vision was his primary goal. Car chases and explosions were fun, but creating mood and using organic sounds to reflect the inner life of characters and draw in the viewer were what intrigued him the most. Maurice was staunchly pro-worker and pro-union. Years ago, during a round of contract negotiations, the idea of inserting a “no strike” clause in the union contract was floated. Maurice went ballistic at the idea of giving up that essential bargaining tool. He never hired an unpaid intern. He forbade anyone on his crew to work extra hours without being paid overtime. He haggled with producers to hire as many people as possible for as long a time as possible. Even as budgets tightened over the years, if a director wanted him, he knew he had leverage and wouldn’t budge. I remember one particular phone call in which Maurice was vehemently demanding an extra week or a higher salary for one of his editors. In an act of pure vindictiveness, the producer/director offered the supervising job on his next film to the aforementioned editor. Maurice didn’t care. We laughed about it.

Maurice was the first New York sound editor to get into the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) and he encouraged others to apply. Lea inherited the film buff gene and around the winter holidays, when the screeners came in the mail (before streaming), she and Maurice would watch four a day. Two was my limit. He took the voting seriously and wanted to see as much as possible. We’d follow with a great dinner and discussion. We were all quite opinionated and sometimes had to resort to hand raising so each of us could get a word in. It was great fun.

We loved to travel and were usually drawn back to our French and Italian roots. Maurice had retained fluent knowledge of French and to hear this wisecracking New Yorker segue into a soft-spoken Frenchman was a beautiful thing. Of course he would instantly revert to his NYC persona if he detected an anti-American attitude. He related a story about ordering drinks in a Parisian cafe with some French friends. The waiter pegged him for an American and snidely asked if he wanted a Coca-Cola. “Yeah,” Maurice replied, “but not the puny bottles you have here,” gesturing to the small green coke bottles at another table. Raising his hand high, he said: “In America we have BIG ONES!”.

Which brings me to the story of Maurice’s suitcase. Before I knew him he would take off for Paris every chance he got, even if it was a four day break between jobs. On one such trip, a beautiful Florentine leather suitcase that he had treated himself to was missing when he arrived in Paris. He was given a voucher to be taken to the Air France building, a skyscraper in the Montparnasse neighborhood. He started on a low floor. A representative chided him for not removing his hat. She then offered the modest sum indicated in the fine print of his airline ticket that was allotted for lost luggage, which represented a fraction of what his precious suitcase and lost clothing were worth. Not only did he not remove his hat, but, speaking in English, he demanded to see someone above her.

Over the course of several days, up the skyscraper he went, repeatedly being refused a larger sum for his belongings while he pretended not to understand the comments being exchanged among the Air France employees. Finally he broke into flawless French and demanded to see someone higher up the chain.

He was brought to the office of a distinguished, gray-haired executive some floors up who once again refused him any more than the ticket allowed. Maurice then became verbally abusive and demanded to see his superior, to which the outraged gentleman replied, “Never, never has anyone spoken to me this way!” Pointing to a pin on his lapel he said, “Monsieur, I was a prisoner of war!!!” Maurice pounded on the desk with his two fists. “I don’t GIVE a f___ if you were a prisoner of war! I WANT MY SUITCASE!”

He was finally taken to the top of the skyscraper, where a preppy young man who was the assistant to the president of Air France handed him a check for the amount he wanted. “It’s the principle of the thing,” he said. Pointing from the window to the pedestrians way down below, he said, ‘You work for those people. If Richard Burton or Elizabeth Taylor lost a suitcase you would put them up in a hotel and pay for all their belongings!” It’s a story he delighted in telling and we never got tired of hearing it.

He was notorious for battling things out in the halls of New York’s Sound One as well. There was a production supervisor who had a reputation for being particularly abusive to the editing staff. One day he started in on Maurice. “You’ve got the wrong guy,” Maurice warned. He kept it up. Maurice lunged at him. Bins, cores and cookies went flying. Irwin Simon and Chuck Spera, who rented the editing room equipment, had to break it up. “When they go low, we go high” was not Maurice’s motto. When confronted by a bully, you had to react fast and hard, and he’d think twice about messing with you again.

Watching the rise in authoritarianism in recent years was painful for him. “I’m leaving the same world I came into,” he said. His health declined slowly in the past year and a half due to a blood disease, myelodisplastic syndrome. He became weaker and weaker, and would apologize for being dependent on me for everything. I told him it was a privilege to care for him and it was. To Lea and me, he would always be our fearless warrior, except he once confessed to me that he was afraid when standing up to a bully or speaking truth to power.

But one had to do the right thing.

A beautiful portrait of a beautiful and talented man.

What a beautifully written and moving tribute. Thank you for sharing your stories of Maurice, a legend in the New York film world and beyond.

What a beautiful tribute. You were both so lucky to have each other! xoxo