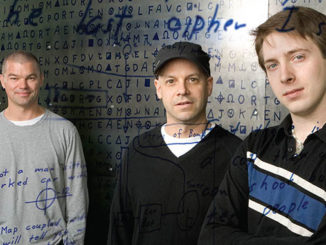

by Peter Tonguette • portrait by Martin Cohen

Few people are privy to the secrets of filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s new science-fiction adventure Interstellar — and those who are aren’t talking. One person who knows Interstellar more intimately than most is editor Lee Smith, ACE, who has worked with Nolan for close to a decade. Interstellar, which Paramount Pictures releases November 7, is their sixth collaboration. Although Smith is necessarily short on specifics, he promises that the film will amaze. “I’m thrilled to have worked on it,” he says. “It’s just one of those once-in-a- lifetime movies.”

Matthew McConaughey plays the film’s hero, an engineer who is forced to reinvent himself as an astronaut when the Earth is in the throes of a calamity. He may be seeking a new planet — and thus the preservation of human life — but the process means an extended (and intergalactic) leave of absence from his young family. McConaughey’s co-stars include Anne Hathaway (who joins him on his journey into the galaxy), Jessica Chastain, Ellen Burstyn and Michael Caine, but the real star, perhaps, is the scale of the project. “It’s a very epic story of space travel,” Smith says. “And everything that excites me about filmmaking is exploration.”

A native of London, England who grew up in Sydney, Australia, Smith began his own voyage in the film industry more than three decades ago. He started as an apprentice at a post-production house in his hometown, where his duties ranged from edge numbering to making tea, he says. He worked as a sound editor before eventually breaking into picture editing, assisting or cutting films for such prominent Australian directors as Bruce Beresford and Peter Weir.

Shortly after Smith finished work on Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003) for Weir, his agent called with a question: Was he interested in editing a Batman movie? “To which I think my first response was, ‘No,’” Smith recalls, though his curiosity was aroused when he did some homework on the project’s director, Nolan. Smith had never seen Memento (2000) nor Insomnia (2002), so he sat down with the films before giving his agent his answer: “I agreed with her that, yeah, this young guy — he had a future.”

After meeting and deciding to work together, Smith and Nolan found that they were simpatico. “I think the editor-and-director relationship is an interesting one, where it’s kind of like a marriage in a way — you have to be on the same page aesthetically, technically, dramatically,” Smith says.

Nolan, who worked with Dody Dorn, ACE, on Memento and Insomnia, agrees: “I love working with the same editor because you develop a very close

relationship with the person. In the edit suite, you spend an enormous amount of time together trying out different things. And once you find somebody that you really click with in terms of your technical approach to cutting and your overall creative vision — and then your personalities — I think you definitely want to repeat that experience and try to build on the relationship. And that’s been very productive for myself and Lee.”

But their collaboration on Batman Begins (2005) got underway with Nolan asking Smith to change course from one of his previous habits. In all of his previous films, Smith, like most editors, cut scenes with the aid of temp music. Nolan asked him to stop. “He said, ‘I know you’ve probably done it like this your entire life,’” Smith remembers. “I said, ‘Yes, I’m normally carrying temp music pretty well from the get-go.’ And he said, ‘I just want you to try to cut the entire first cut without using any music whatsoever.’”

It was a tall order, but as Smith dove into Batman Begins, he realized that the film was benefitting from the decision to abstain from temp music. “It makes you very, very, hard on the footage because as soon as you put music on, everything looks better; music is the great glue,” he explains. Smith found he was forced to reckon with scenes that played very slowly without music, with an eye to shortening them for maximum effect — even though he knew that they would later be helped by the addition of a score. “It just gives you a laser focus on not letting stuff just go on forever,” he says. “Chris writes a very full, very big script, but you still have to get it down to a manageable piece of entertainment.”

Nolan adds, “I’ve always worked without sound effects to begin with, and then without music. So we build the film in layers; we cut with just picture and dialogue, then we start to layer in some sound, then we start to put music in. Music always deceives you in terms of the effectiveness of your pacing — that’s the key thing — and in terms of your mood.”

Smith came to share Nolan’s view that the time to add music was after the film has been “figured out,” although the two have modified their process on recent films, Interstellar included. No temp music was used either during the first assembly or in the early stages of the director’s cut, but as post-production continued, composer Hans Zimmer (who also wrote the music for other recent Nolan films) started sending musical suites inspired by the screenplay alone. Smith describes this material as “the genesis of the score,” adding, “At about week five of the director’s cut, we showed Hans the film and he continued to supply music from that point to the final mix.” The process, Smith says, avoids the pitfall of “temp love,” wherein filmmakers become wedded to music that will never end up in the finished film.

Nolan, who co-edited his first film, Following (1998), with Gareth Heal, has a sure feel for what goes into post-production. “I don’t think I’ve met anyone else who knows more about my job than me,” Smith says, adding that Nolan almost always gives him all of the material with which he needs to work. “Sometimes on films, you’re coming up with pages of notes of extra shots or ideas,” the editor continues, emphasizing that with Nolan, “It’s pretty rare when I can actually find something I can sort of request. I’m given a mountain of footage, and I go figure it out for myself.”

“I don’t look at his cuts, I don’t look at the assembly, unless he says there’s a problem,” Nolan acknowledges. “If he says we’re missing something, I’ll pop in and take a look at it.” Although Smith communicates with Nolan during production, and the two take time to talk during dailies, the director leaves the editor alone to do his job, not becoming involved in post-production until after filming has wrapped.

“I think Chris likes that sort of fresh look at something,” Smith says. “He’s been thinking about something one way, and I interpret it a slightly different way.” Once Nolan joins Smith, the director says they will more or less start over: “We’ll use elements of what Lee’s put together, but we actually enjoy the luxury of going back to all the dailies and reviewing everything.”

Nolan adds, “Lee’s assembly would always be a cut that you could probably quite happily release into theatres — he’s that skilled. But the truth is that there’s a great pleasure and great productivity in the exploration of all the different possibilities of the material that was shot.” The director says that his strongest opinions often relate to a given scene’s point of view. He asks, “Which character are we aligned with? Who are we looking to sympathize with? How are we guiding the audience to a particular place in terms of point of view? That’s a lot of what we play around with in the edit.” Sequences using parallel action or cross-cutting also require a lot of work in post- production. “Very often, it’s not going to be apparent from the dailies as to how exactly I’m intending to put those things together,” Nolan says.

Cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, NSC, FSF, used 35mm and IMAX formats for Interstellar, a commingling previously used by Nolan and DP Wally Pfister, ASC, on The Dark Knight (2008) and The Dark Knight Rises (2012). “The prologue and several action sequences were shot on IMAX,” Smith says of the earlier film, and he quickly realized that fusing the formats did not present insurmountable problems in the cutting room.

“You had to keep an eye on it as far as going from dark to light,” the editor explains. “Very rarely, but occasionally, the cut would pop.” When editing on one of the eight Avids used to cut Interstellar, Smith says, “The IMAX is layered on the lower vision track with a Cinemascope extraction above it, so we are seeing the Cinemascope version of the movie the majority of the time. We have a set-up where we can screen the IMAX and the Cinemascope in combination, which we look at more as the film approaches the final cut, at which point we go on to complete the IMAX release of the film.”

The format is used in Interstellar in much the same way as it was in The Dark Knight — for the occasional long shot or for scenes involving action without much dialogue. “What I like about it from an editing standpoint is that some sequences just lend themselves to this vast IMAX screen,” Smith says. “Dramatically, when the sequence would go wide or start wide or cut into an establishing shot with the IMAX format, it did give you a rush and a certain sense of exhilarational vertigo.”

Although, Nolan adds, because van Hoytema figured out a way to hand-hold the IMAX camera — and because the camera’s noise was unimportant when recording sound in space helmets — “We were actually able to get a bigger range of scenes than we’d gotten before; we captured intimate moments as well as very spontaneous and energetic moments with the camera that we wouldn’t have been able to do on the other films.”

“Music always deceives you in terms of the effectiveness of your pacing — that’s the key thing — and in terms of your mood.”

– Christopher Nolan

IMAX dailies were saved for special half-day sessions on an IMAX screen, according to Smith. With reduction prints already struck and the scenes already in the Avid, viewing the material in its original format is a bit “like Christmas,” he says. “By then, you’ve kind of forgotten what you shot. We print selected footage to 70mm and have a look at it. It’s always very invigorating to watch that stuff roll through.”

One of Nolan’s strong preferences is to use production dialogue whenever possible. Only six hours of ADR was recorded on Interstellar, Smith says, “as opposed to weeks and weeks of what you would expect to record on a conventional action film.” Supervising sound editor Richard King, along with re-recording mixers Gregg Landaker and Gary Rizzo, CAS, have been working with Nolan for most of the Batman years. Together, they have eschewed pre-dubbing in favor of a “rolling temp dub,” which was, Smith says, requested by Nolan “as a reaction to putting a lot of effort and ideas into the first temp and then having to effectively start again for the final mix. It was a cool way to streamline the process and was embraced by Richard, Gary and Gregg.”

Although Interstellar has its share of fire-spewing rockets and spaceships landing on faraway planets, Nolan is cautious when it comes to computer-generated imagery. “There is certainly a CG component to the movie because, obviously, it’s difficult to send people to space without that aid,” Smith says, careful to point out that the film is not dominated by CG effects or environments. “This is very much a film that’s being shot to look real and is tactile.” Interstellar was filmed on locations in Canada, Iceland and Los Angeles.

The otherworldly elements were often introduced on set rather than in post-production, according to Smith. “I think what makes it such a great film is that you can sort of understand and associate with it because there is so much reality in the frame, even if what you’re looking at you believe to be other worlds.”

Summing up the experience of editing Interstellar, Smith says with a laugh, “To be cheesy, it’s out of this world, man, out of this world.”