By Patrick Z. McGavin

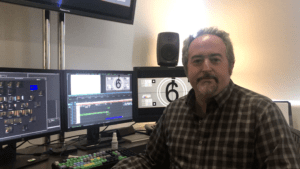

Born in Panama, JC Bond was 21 when he arrived in the US and studied filmmaking at the University of Miami in the late 1980s.

After extensive work as a visual effects editor, associate, first assistant or additional editor, Bond earned his first significant solo credit on Tim Burton’s “Big Eyes” (2014).

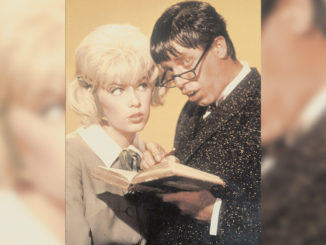

His latest project was cutting “Chemical Hearts,” the second feature by Richard Tanne. The story charts the fraught emotional relationship of an aspiring young writer Henry (Austin Abrams) and the mysterious new transfer student, Grace Town (Lili Reinhart), eager to escape her tragic past.

The movie is now available on the streaming platform Amazon Prime. In an interview, Bond talked about the this intimate chamber drama with a twist.

CineMontage: How would you describe your creative relationship with the writer/director, Richard Tanne?

JC Bond: It was an amazing collaboration. When I was hired for the project, Richard was already on location in New Jersey. So we didn’t have much time to talk, at least in person, before the project.

Once the project got started, he indicated two or three times a week of what he wanted, sometimes daily depending on what was happening on set. Once they finished shooting, it was like a match made in heaven. We were very comfortable with each other.

Was he in the room with you?

Once shooting was finished, I still had a little bit of time to finish my assembly. After that, Richard was in the cutting room with me 12 hours a day, every day of the week.

He also adapted the novel by Krystal Sutherland. Did you find he was pretty protective of the material, or did he allow you the autonomy to experiment with your own ideas?

On one level I am sometimes very nervous of working with writer-directors because of that. Richard was the first one to say: “Let’s lose that,” or “I see now this is not working as I imagined it. Let’s throw it out and figure something else.”

It was a really collaborative effort. We experimented and brought new ideas, new stories, new ways of presenting the material.

What was your research like? Did you read the novel, or the script, or do you like to go into a project more open?

I definitely read the script multiple times. I did spend a little bit of time researching what the background was to the original novel, but I didn’t want to read the novel, especially because as a filmmaker in the editing room, I need to be that audience.

I need to know what the audience knows and nothing more. Reading the novel would probably have given me information that wasn’t present on the screen. I needed to limit myself to making sure the audience looking at the movie would be able to understand the movie without having to read the novel.

The movie was shot in 35mm, and it has a very particular texture? What did that mean for your work, as opposed to something shot in digital capture?

I have been in this industry for more than 25 years. So I started with everything shot on film and initially things edited on film. Obviously back then, I was an assistant. Shooting on film was actually refreshing. It is a challenge, with little things here and there.

I wasn’t getting the dailies the next day, because let’s face it, film has been relegated to a secondary medium. The film gets processed one day, then it gets scanned the following day. I was almost three days behind the camera. That was the biggest hurdle.

On a movie like this that had a very short shooting schedule, by the time I got dailies they had already moved on from a particular location. I did put in requests during shooting: “It would be nice to get this,” and Richard would do his best to either go back to that location or fake the location and get whatever we needed.

Regardless of the scale, every movie has its own difficulties and complications. What was the most challenging part of this film?

The biggest challenge was to keep the movie focused. The script was originally a little bit longer than the movie is today.

My original assembly included everything that we shot. Our main objective was getting the movie focused on what it needed to be. There were side stories, side characters, that in the long run just didn’t need to be there. That’s what editing is.

Point of view is very interesting here. Henry (Austin Abrams) is the ostensible hero and narrator. Grace (Lili Reinhart) is the one who really drives the conflict and the story. How did you disentangle that?

That was a process that started with photography and planning, and it continued well into post. Richard was always very cautious of making sure every scene that Henry was the narrator, the one experiencing all of this, so if you look through the movie, you won’t find a scene where Grace is on her own because Henry would not have been there.

It is always keeping the movie focused on Henry’s POV and what is happening around him.

There are two crucial scenes in the movie that take place in an abandoned factory. There are very specific uses of water, the first highly sexual and the second time signifying rebirth. Were they designed as bookends?

Absolutely. The return to the location and the environment was crucial. That was the place where Grace opened up. It’s also the place where she went to cleanse herself. Those two scenes are probably the two we spent the most amount of time molding and making sure we got correct.

I have often thought high school movies are sometimes the only serious depictions of how class differences operate in this country. It seems pretty striking here the backgrounds of the two leads.

That was something we talked about a lot with Grace being from a broken home and Henry coming from a home in which everything was perfect. It was the contrast between the two that made their relationship and their experience so different.

Richard Tanne is from Livingston, New Jersey. Is it fairly autobiographical for him?

The story is obviously based on the novel. There are several elements of the movie that are autobiographical for Richard, like the fact Richard was a newspaper editor at his high school. That’s why he wanted to shoot the movie in New Jersey. That was him going back and showing his own personal experiences through that.

A movie like this ultimately works because of the actors. What is your process like in shaping performances?

We were extremely lucky on this project to have actors like Lili and Austin; these actors were amazing. Our job in the cutting room was about letting those performances shine. Let’s cut out everything that is not needed. That was the shaping. Let’s take out what doesn’t need to be there, and make sure the performances they brought to the table are on the screen.

You have worked on a lot of effects-heavy films. This movie feels more hand made. Was that appealing for you?

I love good stories. Visual effects are nothing if they don’t support the story you are driving. I love the world of visual effects. I am very comfortable in it. The main focus on every movie is to carry a story. That’s what a script is. That’s the focus.

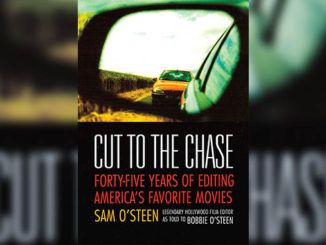

Your background is very versatile, in visual effects, associate, first and additional editor on very expensive studio projects. How do you feel like that background shape now as you have made the leap into being the primary editor?

Throughout my many years in the cutting room and working in things other than editor, I was very fortunate in having great mentors and being able to learn from them.

The basic things of creating stories or all these concepts you can read about when you go to film school or be told that these things are necessary, but the reality is until you experience them and you are in the cutting room and you see how raw footage becoming really emotional—touching things—that’s what it is all about.

Did you start out to become an editor or did you gravitate it after studying different film disciplines?

Initially when I was in film school I had this idea I was going to become a producer or line producer. As a matter of fact one of my first jobs out of film school was as a line producer on a small project. Editing came afterwards, even though in film school I was always the editor on my projects or films I would help other classmates.

I didn’t originally see myself as an editor, at least not while I was going to film school. I fell in love with post-production later when I was noticing where the movie was really being made. That’s what attracted me to editing and post-production.

Do you subscribe to the theories of montage and synthesis, or do you prefer the more classic period invisible style of cutting?

I am more about the invisible editing style. I want the audience to come and experience the story. I don’t want them necessarily paying attention to technical aspects or special effects. I am a storyteller. I may not be a director, I may not be an actor, I may not be a writer. In my way of the cutting room, I am here to shape and mold the story. That’s why I am there.

The very nature of film audiences has changed rapidly. “Chemical Hearts” is showing exclusively on the streaming platform of probably the best-known company in the world.

It’s actually an amazing experience. I believe that every movie has a place and a sense where it needs to be experienced. I think this is a perfect movie for this platform. It’s a very personal experience, a very personal story. By being on a platform like Amazon Prime, it is going to be viewed by millions of people. It will be put in front of millions of people to get its audience. That will end up much larger than it ever [would have] as a theatrical release.

Patrick Z. McGavin is a Chicago-based writer and cultural critic.