by Peter Tonguette

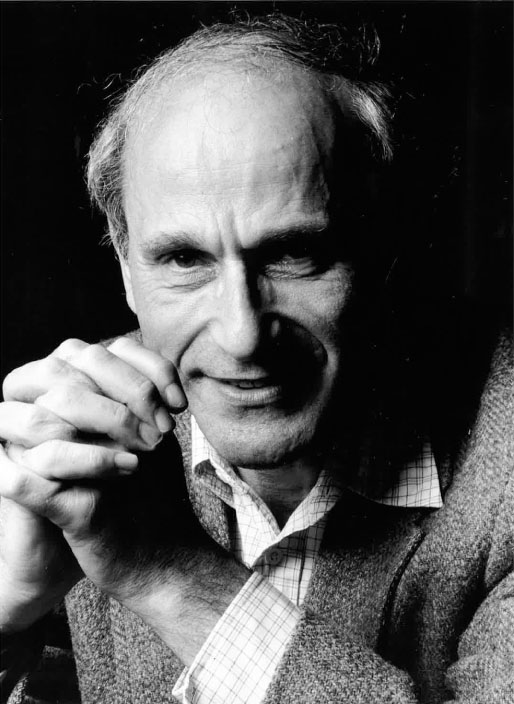

In the early 1960s, when he first met director Karel Reisz, editor John Bloom already knew his way around a cutting room. By then, the London-born editor had risen through the ranks as an assistant editor to cut several films solo, and was only a few years away from the swinging London comedy that established his reputation: Georgy Girl (1966).

But Reisz, who was collaborating with Bloom on commercials for British television, was no amateur when it came to post-production — or so it was fair to assume. Before beginning his directorial career, which came to include such widely admired films as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), The Gambler (1974) and Sweet Dreams (1985), the native of Czechoslovakia co-authored a book with Gavin Millar entitled The Technique of Film Editing, published in 1954.

As far as Bloom was concerned, Reisz’s reputation preceded him. “Karel came into the cutting room to have a look, and I thought I would defer to the man who had written one of the definitive books on film editing,” Bloom remembers. “I said, ‘Karel, would you like to run the film yourself rather than me?’ He just looked and me and in that wonderful, slow, perfectly enunciated English accent — a language he hadn’t learned until coming to England as a Czechoslovak refugee at the age of 18 — he said, ‘I don’t know how.’ I said, ‘Karel, you’ve written a book on editing.’ ‘He said, ‘I know, but I wrote it at university. It was all theory. I have never physically edited.’”

With their days working on commercials behind them, Reisz would call on Bloom’s cutting room acumen on a trio of impressive feature films: Who’ll Stop the Rain (1978), The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981) and Everybody Wins (1990). Yet Bloom says that Reisz remained modest throughout their collaboration, eagerly soliciting comments or criticism.

“Karel welcomed being challenged about what he had done,” Bloom recounts. “I wasn’t afraid in coming forward as far as that was concerned, and it only helped to make our bond even more secure. Karel liked a good fight. We really did have a wonderful relationship and wonderful friendship.”

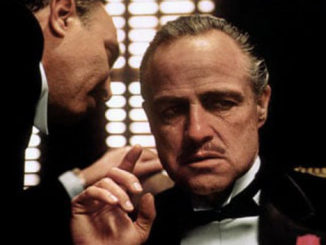

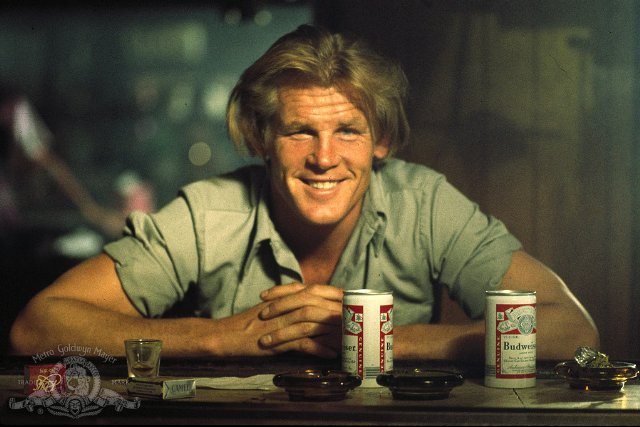

Based upon Robert Stone’s Vietnam War-set novel Dog Soldiers, Who’ll Stop the Rain — Bloom’s favorite of his three films with Reisz — has as its center a trio of flawed characters: reporter John Converse (Michael Moriarty), his wife Marge (Tuesday Weld) and one of his oldest and closest friends, Merchant Marine Ray Hicks (Nick Nolte).

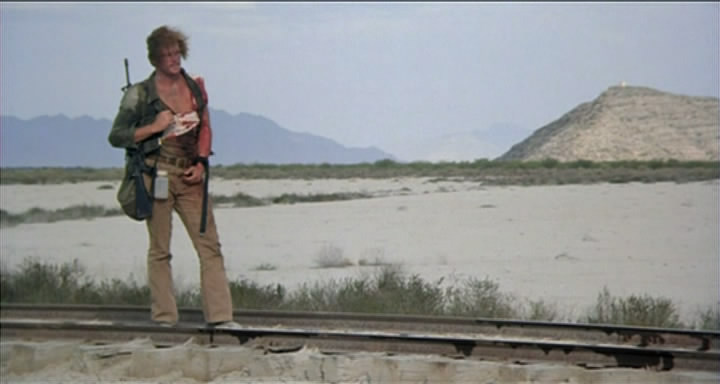

While both men are still overseas, Converse prevails upon Hicks to smuggle a parcel of drugs into the United States; Hicks intends to sell the package for a profit, though he gives little indication of having thought through the scheme. A character of rare strength and self-sufficiency, Hicks goes along with the idea, but mainly as a test of his own smarts — can he really pull it off? Alas, the deal is undone when Converse falls into the clutches of heavies (including Richard Masur’s Danskin and Ray Sharkey’s Smitty), while Hicks and Marge strike out on their own, the illegal substance in tow. Who’ll Stop the Rain captures the bad vibes — and bad drug deals — of the era with admirable acuity.

“It’s a film about the Vietnam War in which the war is portrayed hardly at all bu,t to my mind, is far more interesting in that it shows the way the war has polluted the minds of ordinary, decent people and turned them into corrupt outsiders,” Bloom says. “The film shows that the war has allowed people’s moral compasses to collapse, justifying their desire to get something out of the whole mess.

“Nick Nolte is simply superb as Hicks, as is Michael Moriarty as Converse,” Bloom continues. “Tuesday Weld never did anything better than this as Marge, the person for whom the word ‘indecisive’ might have been created. I do not believe there’s ever been a better pair of villains than Richard Masur and Ray Sharkey — funny and terrifying in equal measure.”

Who’ll Stop the Rain was one of the first American productions on which Bloom worked. The younger brother of actress Claire Bloom, he entered the business in the story department of Pinewood Studios, a job he won with the help of his sister’s agent. “There were several resident producers, and you would read the latest books or go to a new play, and then write synopses and critiques,” Bloom says. “I worked there with Lukas Heller, who went on to write Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), and one day he said to me, ‘I’ve never asked you this, but why are you here in the department?’”

Bloom repeated a version of the classic line: What he really wanted to do was direct. Presciently, Heller replied, “Well, why don’t you think of going into the cutting room? That’s a very good introduction to the world of directing, and you’ll learn an awful lot.” Bloom, however, never made the switch to directing. Instead, he preferred to work with leading directors in England and the US, including Anthony Harvey (three films, including 1968’s A Lion in Winter), Bob Rafelson (1987’s Black Widow), Robert Benton (1994’s Nobody’s Fool) and Mike Nichols (four projects, including the director’s final film, 2007’s Charlie Wilson’s War). He earned an Oscar for the second of his three films with Richard Attenborough, the epic Gandhi (1982).

Bloom and Reisz reconnected in the early 1970s, when the director asked the editor to cut The Gambler, a 1970s-era update of a story by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Tied up with another project, Bloom suggested Roger Spottiswoode, among the editors of Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), who was later one of the producers of Who’ll Stop the Rain. This time, Bloom was available to work on Reisz’s film.

Production began in California — with location shooting in Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento and San Francisco — before proceeding to Durango, Mexico, which doubled for New Mexico, where Hicks and Marge square off with their pursuers in a mountainous hiding place. Bloom, who shared a house with Reisz and Spottiswoode outside of Durango, was with the company for the duration. “I do like being part of the whole outfit,” he says. “It was quite a lot of moves, actually.”

As shooting continued, Bloom began assembling the material, but his work with Reisz didn’t begin in earnest until the film wrapped. “I don’t think Karel saw very much as we went along,” Bloom comments. “He wanted to wait until we got in the cutting room.”

Among the trickiest scenes to pull together was the film’s impressionistic prologue in Vietnam, where Converse and Hicks renew acquaintances and broker their deal. In the film’s first image, Converse is seen ducking in a foxhole while explosions fill the screen. The shot was initially intended to stand on its own, but Bloom decided to fold it into the story as a flashback, intercutting the image with shots of Converse writing a letter to Marge and being driven in a Jeep to meet Hicks.

“We felt it was an essential part of the movie, but really didn’t quite know how to integrate it,” Bloom concedes. “It just seemed to happen and there was no background to it whatsoever, and then I had a bit of a eureka moment when I suggested trying to integrate it into the scene where they’re driving. That was very satisfying from Karel’s point-of-view.”

Cinematographer Freddie Francis, who collaborated with Reisz on several films, including The French Lieutenant’s Woman, remembers the director as being on the indecisive side. “He had the knack of annoying me with little things,” Francis wrote in his memoir, The Straight Story from Moby Dick to Glory, “fussing over nothing instead of relying on me to do the task.” Bloom confirms this impression, remembering a single 90-second scene with Converse and Marge in a Jeep that Reisz spent a week reworking. “We tried every, every which way back and forth,” Bloom says. “I was completely exhausted and my assistant at the time, Peter Boyle [not the late actor], was lying on the floor. He couldn’t take it anymore. At which point, Karel looked at me and said, ‘I think the original version was better.’”

Yet Reisz’s perfectionism was not necessarily a liability, according to the editor. “I say that in the most loving way,” Bloom observes. “There was nothing Karel wouldn’t try to make something work, and he had a wonderful, marvelous eye and instinct for when it did.”

On the whole, however, Bloom felt that the film fell together readily, despite its dramatic shifts in tone. In one scene, for example, Hicks has been introduced to a naïve couple purportedly interested in acquiring the package of drugs, but when he realizes the pair are amateurs, he intentionally causes them to overdose. The scene is simultaneously humorous and horrifying. “I consider the scene to be one of the most terrifying about drug-taking that I have ever seen, with Nolte superb in his depiction of true vindictiveness,” Bloom comments. “I take pride in having chosen to use the [musical] piece of Indian raga that accompanies the scene. From this gentle beginning, it develops into a frenetic tempo, which accents the brutality of the scene.”

Despite the then-current vogue for films set during the Vietnam War — including Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) — Who’ll Stop the Rain failed to find an audience when released by United Artists. Bloom attributes its lack of commercial success in part to the change in title from that of the original novel, Dog Soldiers. “The distribution people decided to go into various malls in California and ask people whether they would be interested in seeing a film called Dog Soldiers,” Bloom recounts. “People were saying, ‘Oh, I don’t want to see a film about dogs.’ And other people were saying, ‘Nah, I don’t want to see a film about soldiers.’ So they panicked.”

In the end, Who’ll Stop the Rain was chosen as a reference to the hitsong of the same name by Creedence Clearwater Revival, whose music is used to evocative effect throughout the film to complement the score by composer Laurence Rosenthal. “We were given the absolute rights to use any of the music that we wanted from that period,” Bloom says. “We particularly fell in love with Creedence’s numbers, which seemed absolutely right for the film.”

But not, alas, for the title. “It’s fine for a song, thank you very much, but for a movie — a disaster,” Bloom reflects. “Even to this day, I’m kind of embarrassed if I have to mention the title. I often say: ‘Please believe me — it’s a wonderful film!’”