by Ray Zone

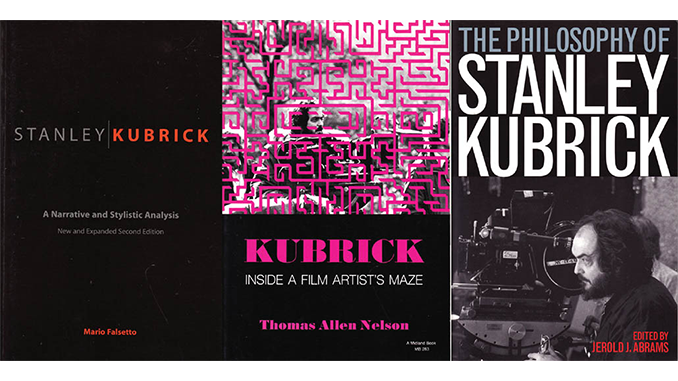

Stanley Kubrick

A Narrative and Stylistic Analysis (Second Edition)

by Mario Falsetto

Praeger Publishers

206 pps. paperbound, $55.66 (price varies)

ISBN: 0-275-97291-7

Kubrick

Inside A Film Artist’s Maze

by Thomas Allen Nelson

Indiana University Press

268 pps. paperbound, $10.46 (price varies)

ISBN: 0-253-14648-8

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick

Edited by Jerold J. Abrams

University Press of Kentucky

278 pps. paperbound, $19.95

ISBN: 978-0-8131-9220-8

Spatial and temporal manipulations are a necessary part of both editing and camera-related strategies,” writes Mario Falsetto in his pioneering study of the films of Stanley Kubrick. “Every shot encloses space and also has a temporal factor in the form of shot length. All editing decisions thus involve duration and spatial considerations.” These two artistic poles of film construction and storytelling could accurately be characterized as montage, as derived from the school of Pudovkin and Eisenstein, emphasizing temporal construction and mise-en-scene as championed by André Bazin and focusing on the space within the film frame and the arrangement of visual components therein.

With his illuminating study of Kubrick’s film aesthetics, Thomas Allen Nelson notes that “a widely known but uninvestigated source” for an understanding of them can be found in Pudovkin’s book Film Technique.” Kubrick has characterized Pudovkin’s book as the “most instructive book on film aesthetics I came across.” Allen observes that “Kubrick’s films stand as a testament to a meticulous architectonics in the organization of their temporal rhetoric” and that Kubrick had “gained an increasing control and mastery” over the “temporal aesthetics of film.”

Despite this, however, it’s fair to say that Kubrick, as a rule, favored deep focus and longer running time for individual shots rather than the fast cutting of montage. “I like the slow start,” he stated in a 1957 Newsweek article, “The start that goes under the audience’s skin and involves them so they can appreciate grace notes and soft tones and don’t have to be pounded over the head with plot points and suspense hooks.” Revelation of character as well, for Kubrick, was a measured development in which “you let the character unfold himself gradually before the audience. You hold off as long as possible in revealing the kind he is.”

In exploring the long take and spatial arrangements within the film frame itself, Kubrick was artistically out of step with his contemporaries.

Allen also adds that Bazin, with his seminal essay on “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema” addressing deep focus in the films of William Wyler (The Little Foxes, 1941) and Orson Welles (Citizen Kane, 1940) and the absence of montage effects in Italian neorealist cinema, provides “the kind of critical clarity and relevance necessary for an analysis of how Kubrick’s aesthetics express a conditional rather than dialectical world view.”

Falsetto rightly notes that Kubrick’s films reveal “a skillful organization and blending of editing patterns and camera strategies.” And, though he acknowledges that “shot-to-shot manipulation” is a vital part of Kubrick’s aesthetic and that it is the “complexity of spatial and temporal manipulations that are at the center of his cinematic achievement,” Falsetto also observes that his films “often favor the long-take, deep-focus style of construction.” Accordingly, the author devotes considerable discussion to Kubrick’s use of the long-take aesthetic.

The use of the long take connects Kubrick to such directors as Jean Renoir, F.W. Murnau, Welles and particularly Max Ophuls––whose influence was greatly in evidence with Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999). As much as Kubrick’s films contain sequences of virtuoso editing, there is an equivalent use of the long take, especially with sequences of dialogue. This pattern was evident even with Kubrick’s early film The Killing (1956). “As used in The Killing, the long take helps efface the passage of time,” writes Falsetto. But he also opines that it can “just as easily force the viewer to attend to the image and the passage of time” and that the slower pace of these scenes act as “breathers from the relentless pace and precise temporal ordering of the rest of the film.”

Kubrick’s most daring use of the long take was very likely his 1975 film Barry Lyndon. With his essay “The Shape of Man” in the new collection edited by Jerold J. Abrams, Chris P. Pliatska examines Kubrick’s unconventional cinematic strategies in Barry Lyndon that embraced a painterly aesthetic incorporating reverse zoom in the long takes. “The camera begins a scene by focusing on one or more figures in close-up and then, ever so slowly, starts to pull back,” writes Pliatska. “The backward movement continues at a slow but deliberate pace, encompassing more and more of the scene within its frame until the figure or figures on which the camera was originally focused are framed within a larger and sometimes overwhelming visual panorama.”

It’s fair to say that Kubrick, as a rule, favored deep focus and longer running time for individual shots rather than the fast cutting of montage.

The reverse zoom, Pliatska contends, is a “visual metaphor” for two conflicting perspectives. The close-up mirrors the individual and personal perspective and the extreme long shot reflects “the external perspective made available by our capacity for reflexive self-awareness.” The camera movement itself then, over the course of the long take, reveals an “inner tension” between these two perspectives.

To some extent, in exploring the long take and spatial arrangements within the film frame itself, Kubrick was artistically out of step with his contemporaries. Younger directors have progressively emphasized a philosophy of montage with faster cutting and increasing use of the extreme close-up combined with hand-held shooting styles. There are exceptions, of course, and we can number Paul Thomas Anderson and Sam Mendes among them.

The films of Stanley Kubrick, rich in their aesthetic complexity, have generated a considerable bibliography. Two of the volumes discussed here, Falsetto’s and Allen’s, are out of print but available––and easily acquired––online. The Abrams collection was just published. Students of the director’s films will be richly rewarded not just by a study of the films themselves, but also by the considerations of Kubrick’s manipulation of cinematic time included within these volumes.