by Edward Landler

“Nothing…that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.”

– The Tempest, Act I, Scene 2

By now, revealing the gender change of the driving character of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest in Julie Taymor’s new film is no spoiler for audiences. The wronged and sometime Duke of Milan, Prospero, has become the wronged Duchess of Milan, Prospera, in the person of Helen Mirren.

One hopes that such a potent sea-change suggests provocative new layers of meaning to spice Shakespeare’s original themes of humanity in natural and civilized states, of experience and self-knowledge, of art and authority. While all of The Tempest’s prior cinematic renditions are somewhat strange, few are as rich as may have been desired.

More than the movies, television has provided direct transpositions of the play. As part of its eight-year effort to air all 37 Shakespeare plays in their entirety, BBC-TV mounted a magisterial (and stodgy) Tempest in 1980 with Michael Hordern playing out Prospero’s artifices as a ceremonial rite of reconciliation. But George Shaefer’s 1960 NBC production, despite shortening the play to 75 minutes, evoked the essential warmth, humor and humanity of the author’s intent with an ethereal set design and a host of charming performances—Maurice Evans’ Prospero, Richard Burton’s Caliban, Roddy McDowall’s Ariel and Lee Remick’s Miranda.

The big screen has shied away from direct presentations of The Tempest and its language. This is no surprise in two early silent films of the play, but one of them, the surviving 1908 British version directed by Percy Stow, clearly depicts the evolving state of film language––“such shapes, such gestures and such sound, expressing (although they want the use of tongue) a kind of excellent dumb discourse.” (Act III, Scene 3)

A 12-minute film, this silent Tempest cuts together intertitles and 17 successive stage-like tableau shots varying between actual woodlands, a stage-construction rocky island cove and ship, and animated lightning against a painted backdrop sky. The first five tableaux reveal how Prospero and Miranda come to the island and how he gains power over Ariel and Caliban––the backstory related in words by Prospero to Miranda in the play. The rest of the tableaux condense the action of the play in mime.

Stow’s film also provides a glimpse of cinema’s growing technical ability to portray to its audiences different characters’ points of view. In a tableau shot, Ferdinand chases Ariel, who stays out of his reach as the sprite leads him through the woods.

As the camera stops and starts again, Ariel seems to disappear instantly from Ferdinand’s sight and, just as instantly, to appear again. The scene cuts to another part of the forest, where Miranda sits in the foreground. Thus, from her perspective, Ferdinand enters the frame in the back- ground chasing… nothing.

The Tempest Goes West

Most film adaptations of The Tempest do not re-create the play itself, but are re- workings of the story in different settings. The first such reformulation was a Western, Yellow Sky, directed by William A. Wellman in 1948. It is easy to speculate that writer W. R. Burnett, an industry veter- an responsible for about 70 story or screen- play credits, drew his original inspiration for this film from a line spoken by one of Shakespeare’s characters. Aboard the ship battered by the storm in the very first scene, Gonzalo says, “Now would I give a thousand furlongs of sea for an acre of barren ground…I would fain die a dry death.”

In Yellow Sky, the intense heat of a desert sun replaces the ocean tempest. The noblemen and their entourage become a band of outlaws fleeing from a bank robbery and a ghost town replaces Prospero’s island. Half-crazed with thirst, the gang stumbles into the dilapidated town to find an old prospector and his granddaughter, who let them drink from the town’s spring.

Hollywood’s narrowing of Shakespeare’s themes emerges in a scene in a saloon, just before the bank robbery. Lined up at the bar, the six outlaws stare longingly at a large, crudely painted landscape with a naked woman tied to the back of a rearing horse. Later, when confronted with Anne Baxter’s formidable rifle-wield- ing Miranda surrogate, “Mike” (for Constance Mae), the robbers stand in for brutish Calibans seeking to violate her honor.

The action then revolves around which of the bad men will rise above their bestial natures to achieve the grace of civilized behavior. Bathing after Mike tells him that he smells, the gang’s leader, “Stretch” Dawson (Gregory Peck), displays changes in his sexual attitudes along with other shifts of social outlook. Rather than going along with the others to steal the prospector’s gold, he sides with the old man and the girl and their plan to use the gold to bring new settlers to the town.

Shakespeare in Space

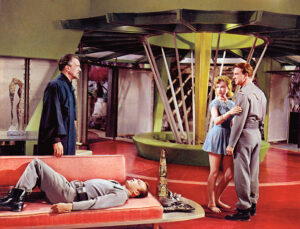

Sexual and social attitudes become more convoluted in Forbidden Planet, MGM’s 1956 science-fiction mutation of The Tempest (see related story, page 64). Played out behind cinema’s first entirely electronic music score (perhaps the “thou- sand twangling instruments” of Prospero’s isle), a spaceship crew from Earth lands under the green skies of Altair-4, hundreds of years in the future, to investigate the fate of an earlier colonizing expedition. They discover the only survivors, Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) and his daughter, Altaira (Anne Francis), living comfortably and being served by their very un-spritelike, electronic Ariel––Robby the Robot.

As Mike does in Yellow Sky, Altaira attracts the attentions of the intruding crew. But unlike the self-reliant Mike, she is dependent on her father and totally innocent of how her physical presence affects these men who have been zooming across light-years in space without females. Early in the film, a wild tiger of the planet acts like a gentle house cat around Altaira. Later, when she responds sensually to crew leader J.J. Adams’ (Leslie Nielsen) kiss, the tiger attacks her and Adams must vaporize the beast into flames in mid-air.

This distorted psychology carries over into the characterization of Forbidden Planet’s Caliban––the human subconscious itself. The original colonizers and some of Adams’ men are torn to pieces by an invisible force that turns out to be a pro- jection of Morbius’s own mind––“such stuff as dreams are made on.” While Morbius sleeps, the advanced technology of the planet’s extinct alien species corpo-realizes this Id Monster from his unconscious to enact his destructive desires.

“We’re all part monsters in our subconscious,” says Adams. “That’s why we have laws and religion.” Thus, Adams and his men––with Altaira and Robby––escape the planet, leaving Morbius on “the great globe itself” to explode in space, and justifying both fear- ful distrust of the intellect and unquestioning acceptance of established and potentially authoritarian social norms.

Enchanted Isle Settings

With Age of Consent (1969), we escape from studio-bound planets and special effects to the natural beauty of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Unable to find sufficient funding for a film of The Tempest with James Mason as Prospero, director

Michael Powell found backing in Australia for this adaptation of a novel by Norman Lindsay incorporating elements of the play. Under the opening credits, sweeping vistas of ocean expanses become beautiful underwater shots that move through coral reefs, then cut into a submerged red starfish and pan over to Mason, who is looking toward the camera through a New York City store display’s aquarium. He plays Bradley Morahan, a celebrated artist gone stale and determined to go into solitude to recover his artistic powers.

Halfway ‘round the world he goes, to a sparsely populated “isle…full of noises, sounds and sweet airs, that give delight.” Landing at the ramshackle dock, Morahan’s approach to his tropical shack of a new home is intercut with extreme close-ups of “the charms of Sycorax––toads, beetles, bats.” This isle, indeed, has its own version of The Tempest’s Sycorax, Caliban’s witch-mother: Ma Ryan, a drunk- en old hag whose beachcomber grand- daughter Cora is played by Taymor’s cur- rent Prospera, Mirren, in her early ‘20s.

Cora assists Morahan like a nimble Ariel and steals like an amoral Caliban. When Morahan discovers that she has stolen a neighbor’s chicken for his dinner, he con-fronts her on the beach. In contrast to the crooked walking stick with which Ma Ryan beats her, Morahan gestures at Cora with a long, straight stick resembling Prospero’s staff. He tells her she must stop stealing and proceeds to civilize her into Miranda. Paying her to pose nude so she can earn enough to start a new life on the mainland, Morahan finds new inspiration for his art. But instead of remaining a daughterly figure, Cora also fulfills his middle-aged fantasy of sexual renewal as well.

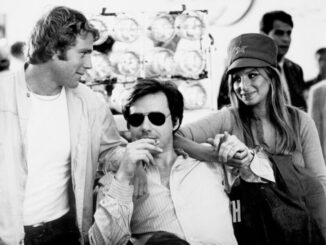

Sexual encounters and fears of aging are central concerns of Tempest, Paul Mazursky’s 1982 modern-day re-working of Shakespeare’s story. Like Powell, Mazursky relies on natural settings to give substance to “the baseless fabric of this vision.” Stunning shots of sunrise and sun- set over a Greek island open and close the tale of John Cassavetes’ New York architect Philip Dimitrius. His wife Antonia (Gena Rowlands) betrays him with a wealthy lover, so Philip flees high society for Greece with their teenage daughter, Miranda (Molly Ringwald). There, he forms a liaison in Athens with Susan Sarandon’s jill-of-all-trades, Aretha, and the three set up house on the rustic island with Raul Julia’s lustful, clarinet-playing Kalibanos as their servant.

Courtesy of World Northal/Photofest. ©World Northal

Mazursky’s story develops through flashback sequences carefully edited by Donn Cambern, A.C.E. A multi-colored striped rug washed by Aretha on a rocky beach becomes a framing image for a key extended look into “the dark backward and abysm of time.” This rug is earlier shown wrapping Philip’s telescope, an image which later triggers and ends the montage of the title storm. Evoking the contrasts and symbiosis of nature and civilization, the lyrically edited tempest upsets the yacht carrying Antonia, along with her industrial tycoon lover, Alonzo (Vittorio Gassman), and his whole entourage.

Avant-Bard

Prior to Taymor’s current film, only two film adaptations of the play actually use Shakespeare’s dialogue, but both are radical departures from theatrical staging and structure. Derek Jarman’s 1979 gay-orient- ed The Tempest “is rounded with a sleep.” It opens with blue-tinted scenes of the storm-tossed ship, intercut by Lesley Walker, with Prospero (Heathcote Williams) in a dark 18th-century mansion, slowly waking from a troubled sleep as if he were dreaming this tempest. The dream completes the film, as well. Rearranging much of the play’s text, Jarman shifts Prospero’s “now are our revels ended” speech to the end of the film. The speech is heard in voiceover as Ariel slips away up the stairs in long shot, away from a now peacefully sleeping Prospero.

Within the dream structure, homoerotic overtones are evoked in Caliban’s servitude to Prospero that become more explicit in the sexplay and transvestism of Caliban, Stephano and Trinculo. Most of the action plays out in shadowy darkness, perhaps reflecting the dreamer’s discomfort with homosexuality. But, at its climax, a cerebration of male sexual attraction bursts out in garish brightness, giving new meaning to Miranda’s words: “How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, that has such people in it.” With the eyes of the male characters intently upon them, 40 col- orfully costumed young sailors dance a hornpipe in concentric circles around a black songstress singing “Stormy Weather.”

The most intellectually rigorous, thematically suggestive and cinematically experimental of all versions (and probably the least engaging emotionally) is Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books (1991). Through the film, 87-year-old John Gielgud as Prospero visualizes, writes and voices all of Shakespeare’s dialogue, until the critical point when he breaks his writing quill––instead of his staff as in the play––and allows his characters to speak their own lines. Interspersed throughout the play’s dialogue, he also voices Greenaway’s scripted descriptions of the books Prospero took with him into exile, “from mine own library…volumes that I prize above my dukedom.”

These 24 books (possibly for film’s 24 frames per second) apparently inspire Prospero’s vision of his play in a constant and elaborate stream of densely layered visuals. In one of the first films to utilize high-definition video technology, Green- away and editor Marina Bodbijl use NHK’s early analogue Hi-Vision HD process to create sumptuous superimpositions of images upon images and frames within frames of action and décor. These highly stylized visuals emphasize the ritual quality of the play over the dramatic, depicting the characters in “the cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces, the solemn temples” peopled with vast numbers of the island’s naked spirits.

Playful imagery fills Prospero’s Books, like Ariel urinating on a model ship in a pool to create the tempest under superimposed animated raindrops. But writing, writing tools and books are ever-present images. The first word of the play is inked on parchment, Prospero’s quill’s tip draws blood out of his wooden desktop and, finally, Prospero and three Ariels (child, adolescent and young man) drown his books “deeper than did plummet sound.” Such images along with the parchment pages of the 24 books themselves apply a visual veneer and continuous commentary over the action that reconciles Prospero with his humanity and his world.

Of all the film variations on The Tempest, only Prospero’s Books underscores the Shakespearean theme of art having the power to influence and even to shape our humanity in all its aspects. The other versions largely limit their adaptations to specific aspects of humanity––culture and nat- ural instinct, sexuality and aging, knowledge and control. But the magic of the richest art and drama is that they integrate and make seamless all facets of being human.

“This rough magic I here abjure,” says Prospero, foreseeing his tale’s end. Whether the stage darkens or the screen fades, “our actors…were all spirits, and are melted into air, into thin air,” leaving us to respond to those spirits that best reconcile us, as Shakespeare intended, to our own humanity.