The Voice of Technology: Soviet Cinema’s Transition to Sound, 1928-1935

by Lilya Kaganovsky

Indiana University Press

Softcover, 271 pages, $36

ISBN #978-0-253-03265-2

by Betsy A. McLane

Few Americans, even those who work with motion picture sound, have heard of the Tagefon and Shorinofon systems, but readers interested in the intricacies of how sound first meshed with cinema can learn about these machines and the artists who used them in Lilya Kaganovsky’s fascinating study, The Voice of Technology: Soviet Cinema’s Transition to Sound 1928-1935.

Few Americans, even those who work with motion picture sound, have heard of the Tagefon and Shorinofon systems, but readers interested in the intricacies of how sound first meshed with cinema can learn about these machines and the artists who used them in Lilya Kaganovsky’s fascinating study, The Voice of Technology: Soviet Cinema’s Transition to Sound 1928-1935.

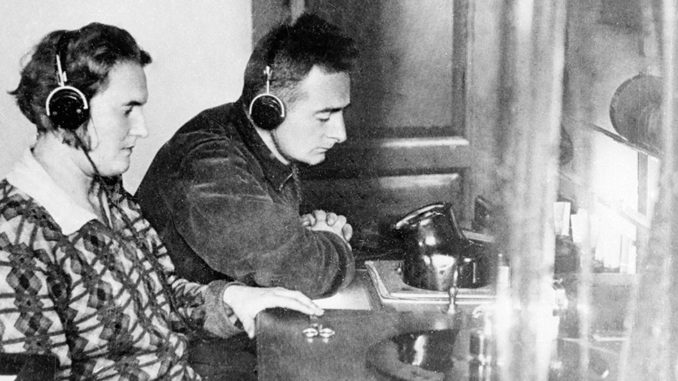

Like most media innovations, the search for a stable sound-on-film system was multi-national and characterized by tangled webs of genius, hard work, collaboration, theft and patent disputes. Kaganovsky does not detail the science of these technologies, but two different systems were developed by Russian inventors, who named their inventions after themselves: Pavel Grigorevich Tager’s Tagefon (1926) and Alexander Shorin’s Shorinofon (1927). The Tagefon was based on intensive variable density optical recording on film, while the Shorinofon, widely used for field and studio sound recording, was based on a mechanical reproduction of gramophone-like longitudinal grooves along the filmstrip.

Both utilized optical sound tracks and were somewhat equivalent to Hollywood systems of the time. There is some evidence that exchange of ideas did take place between the Russians and Americans despite Soviet mandates that the USSR develop its own sound technologies instead of licensing them from the West. (Editor’s note: See related article in CineMontage Q3 2015 [cinemontage.org/2015/12/celebrating-sonic-centennial-everything-wanted-know-history-cinema-sound/] for details of Hollywood’s struggles with sound.)

Most histories of film pay scant attention to such developments in the newly formed Soviet Union, stating only that sound arrived there later than in the West. Even the sound works of Russia’s silent masters — Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Esfir Shub, Aleksandr Dovshenko, Eduard Tissé and others — are generally viewed as inferior to their silent films. Kaganovsky not only explains the complex whys and hows of sound cinema development in the USSR, but also reclaims the artistry and imagination of those who first practiced it.

This subject matter could rightfully be seen as esoteric, but there is much to be learned by those with a passion for film history as well as by contemporary sound designers and editors who may find themselves surprised and even inspired by this book. Kaganovsky’s research is impeccable. Not only does she reference virtually all English-language writing on her subject, she also has combed the archives, unearthing personal stories, government records, filmmakers’ notes, press reviews from the period, and other previously untranslated documents. Her experience as professor of Slavic, Comparative Literature, and Media and Cinema Studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign is put to grand use in this book, and the meticulous footnotes alone tell a new story.

The history of Soviet sound differs greatly from the one of how sound came to film in the US. Not only did Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s face the challenges of flawed emerging technologies, financial risk and artistic adaptation, they were confounded by a policy-shifting, revolutionary government that oversaw artistic and commercial production in every field. Movies were part of Stalin’s Five-Year Plans, and people working at any job in cinema faced the risk of job loss, imprisonment in the gulag or possibly death — just as did “comrades” working in every sector of society.

Although different today, Vladimir Putin’s Russia is modeled on this foundation of media dictatorship. And, as much as we decry the inane policy shifting at the White House, it is good to note that not even Alec Baldwin has been imprisoned.

The early years of Soviet struggle was followed by Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) from 1921 to 1928, which represented a temporary retreat from extreme centralization and produced some of the world’s greatest silent films, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), among others. Cinema was always considered by Soviet leaders to be a prime way to gain support for their agendas, and silent film — with its ability to cross ethnic barriers — was perfectly suited to a nation of 8,649,500 square miles with over 100 different spoken languages. With translated intertitles, a silent film could speak to many millions.

Russian filmmakers also developed a language of silent cinema that reflected the dialectic goals of Marxism meshed with the artistic influences of Constructivism, Agitprop and the vestiges of Futurism. They wrote and debated about their art, its purposes and possibilities in theoretical ways unmatched by filmmakers in the West. They were excited about the possibilities of sound to expand upon their visual montage theories.

Kaganovsky quotes director Vsevolod Pudovkin, who spoke to American photographer Margaret Bourke-White in 1929 (and which she published in her book, Eyes on Russia, 1931) as stating, “Sounds and human speech should be used by the director not as a literal accompaniment, but to amplify and enrich the visual image on screen. …[S]ound film could become a new form of art whose future development had no predictable limits.”

In the Soviet Union, the introduction of sound coincided with “The Great Turning Point,” Stalin’s introduction of the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932). Previously, films were made in service of the Communist revolution, but their creation remained mostly in the hands of filmmakers and regional studios. With the First Five-Year Plan’s total consolidation of the industry under one office came a ban on using any equipment, from camera to film stock to laboratory materials, that were not made solely in the Soviet Union — a trade embargo of gigantic proportions. Since refining and manufacturing sound technology was a slow process, equipment was scarce. Even major directors had to wait in line to use Shorin’s or Tager’s inventions, and that place in line could change at the government’s whim.

The author’s main argument is that because the transition to sound took longer in the USSR, filmmakers “had a chance to experiment with sound to a degree that was unavailable to filmmakers in the US or Europe, [who were] under the pressures of commercial cinema. As a result, they made remarkable films that reflected the chaos but also the possibilities of the new sound apparatus.”

She demonstrates this in detailed discussions in five sections. “The Voice of Technology and the End of Silent Film” is the first, and features Alone (1931), one of many films co-directed by Leonid Trauberg and Grigori Kozintsev. The second, “The Materiality of Sound,” covers Vertov’s Enthusiasm (1930), which the director himself described as “the lead icebreaker in the column of sound newsreels,” and Shub’s K.Sh.E. (Komsomol/Leader of Electrification) (1932).

This subject matter could rightfully be seen as esoteric, but there is much to be learned by those with a passion for film history as well as by contemporary sound designers and editors who may find themselves surprised and even inspired by this book.

Enthusiasm was widely attacked for being a cacophony of sounds, factories, radio, music, bells and speeches — all heard with no particular hierarchy. Vertov was also trying to give the soundtrack weight equal to the visuals, which he forced upon a Film Society of London screening in 1931. According to Kaganovsky, “Vertov insisted on controlling the sound in the projection booth and raising the volume of climaxes to an ear-splitting level, until he ended up being forcibly removed from the projection booth.” She references a note sent to Vertov from Charlie Chaplin calling Enthusiasm, “One of the most exhilarating symphonies I have ever heard.”

Section three of the book explores “Soviet Cinema Learns to Sing” and analyzes Igor Savchenko’s Accordion (1934). This simple musical is based on a poem about a young man who abandons his accordion to become secretary of his Soviet village, but discovers that he is much more prized by the collective as an accordion player. The operetta, as its maker described it, was a forerunner to the Socialist Realism musicals so prized by Stalin, but it still retained too much of the individual artist for the state’s liking so was pulled from all screens, foreign and domestic, in 1936.

The problem of how to make sound films for peoples of many languages is explored in section four, “Multi-Lingualism and Heteroglossia in Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Ivan and Aerograd.” Kaganovsky’s terminology may seem overly academic, but in addition to exploring how the “voice” of cinema was being bent to the demands of Socialist Realism, she chronicles the practical problems of funding, production, distribution and censorship.

Ivan (1932), although cleared by the Politburo, led to Dovzhenko being criticized for using his native Ukrainian language. He remedied this in his next film, Aerograd (1935), a tale about creating a city on the far East Coast of USSR (never built in reality). Despite its characters being from various regions and countries, the only language heard in the film is Russian. Dovzhenko finds alternatives to speech — from mumbling, gestures and hiding of faces to reliance on sound effects and natural noises.

The use of solely Russian dialogue is also a comment on the “voice” of the state, which this film directly addresses when characters speak into the camera, such as an executioner stating, “I am killing a traitor and enemy of the people — my friend, Vasil Petrovich Khudiakov, 60 years old. Be witness to my sorrow.” Thus, the government’s voice is always there to remind people of its authority. It is hard to imagine a Hollywood film of 1935 using sound, or camera, in this way. Even more remarkable is that the sound for Aerograd, like Ivan, was recorded on location.

Section five is again devoted to Vertov and to his Three Songs of Lenin (1934), which over the years, existed in four different versions: two silent and two sound, some of them now lost. It is in this film that Lenin’s voice is heard in sync with picture. Since Vertov wrote prolifically, Kaganovsky is able to recount the process by which assistant director Elizaveta Svilova searched through hundreds of hours of footage, and sound engineer Petr Shtro worked to marry recordings made prior to sound-on-film to these images. Remarkably, in 1933, the team was able to produce sync sound footage of Lenin, who died in 1924, addressing the Red Army: “Stand firm… Stand together… Forward bravely against the foe… Victory shall be ours. The power of the landowners and capitalists, crushed here in Russia, shall be defeated throughout the entire world!”

Fortunately, this did not come to pass — or else Hollywood might be using the Shorinofon!