by Michael Kunkes

One day in 1980, during the editing of The Empire Strikes Back, a slightly frustrated George Lucas turned to assistant editor Duwayne Dunham and said offhandedly, “Someday we’ll have a digital trim bin.” “A what?” Dunham said incredulously. Lucas, calmly, then turned back to his work.

That’s just one of visionary statements contained in the new book Droidmaker: George Lucas and the Digital Revolution (Triad Publishing (ISBN 0-937404-67-5, $34.95). Written by one-time Lucasfilm insider and former Guild editor Michael Rubin in a critical and exploratory fashion, Droidmaker traverses the territory between science and entertainment, and takes the reader inside the early years of Lucasfilm and, particularly, the day-to-day workings of the company’s computer division, which began with the hiring of Ed Catmull in 1979 and effectively ended with the sale of Pixar to Steve Jobs in 1986.

Setting up shop next door to Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) on Kerner Boulevard in San Rafael, California, the Lucasfilm computer division was given carte blanche to come up with ways in which computers could produce significant technological change in editing, sound, imaging and game creation. Attracted by the Star Wars cachet, the best, the brightest and the most iconoclastic came to Lucasfilm—Catmull, Loren Carpenter, James Blinn, Alvy Ray Smith, Rob Cook, Charlie Kellner, Andy Moorer, Ben Burtt, John Lasseter—and dozens of others.

One person who does not appear in Droidmaker is the author himself, who modestly cut himself out of his own book. After graduating from Brown University, Rubin worked at the computer division from 1985-87 in marketing and as an editorial instructor. After he left Lucasfilm, Rubin was product manager and one of the designers of the CMX 600 nonlinear video editing system (and later the architect of the CMX Cinema nonlinear system), as well as being one of the first employees at Sonic Solutions, which had acquired the SoundDroid technology. Rubin later became a Guild assistant editor on projects like Bernado Bertolucci’s The Sheltering Sky. He is also credited as the editor on one of the first TV shows cut on the Avid, 1992’s She-Wolf of London.

In addition to creating numerous seminars, Rubin was among the most ardent nonlinear proponents, and trained many dozens of Guild editors on the EditDroid and CMX 6000 in the 1980s and early ‘90s before writing the classic handbook Nonlinear (now in its fourth edition). He left editing to form his current company, Petroglyph Ceramic Lounge, a Bay Area retail and art studio chain. “After that, I realized that my career as an evangelist for nonlinear editing was going to get a lot less interesting,” Rubin recalls. “My interest in it was about convincing people that it was coming and preparing them for the transition. By 1993, when the adoption of nonlinear really started to happen rapidly, I felt that my work was done.” He was not quite done, however, and became a beta tester for Final Cut Pro in 1998. He also wrote a series of books that included Apple Training Series: iLife05, Making Movies with Final Cut Express and Beginner’s Final Cut Pro.

As the computer division moved toward the completion of the EditDroid, SoundDroid and the Pixar Image Computer, the developments along the way accelerated like the warp drive on the Millennium Falcon—light speed, but with a lot of trial and error. The graphics team pioneered many aspects of 3-D animation for film—motion blur, texture mapping, the alpha channel, particle systems, a rendering system (REYES, the forerunner of Renderman), I/O (input/output) film scanning, star fields, paint systems and modeling systems, all on computers that were today’s equivalents of stone knives and bearskins.

Other key developments at the computer division included “Sybil,” the first EDL (Edit Decision List) generator that cross-related tracking time codes and linked them to key numbers and edge numbers; it was the first relational database between film and video. The landmark invention of the horizontal timeline for the EditDroid and visible sound waveforms in the SoundDroid, “soft” mixing functions, a “spotting” system for searching sound effects libraries and digital signal processing and noise reduction for the SoundDroid were even bigger milestones.

“When people think of Lucasfilm and computers, they think of special effects, but that was just the smallest part of the company’s work,” the author emphasizes. “It is a bittersweet irony that the guy who made this all possible is so famous for Star Wars, that nothing else he does even ranks.

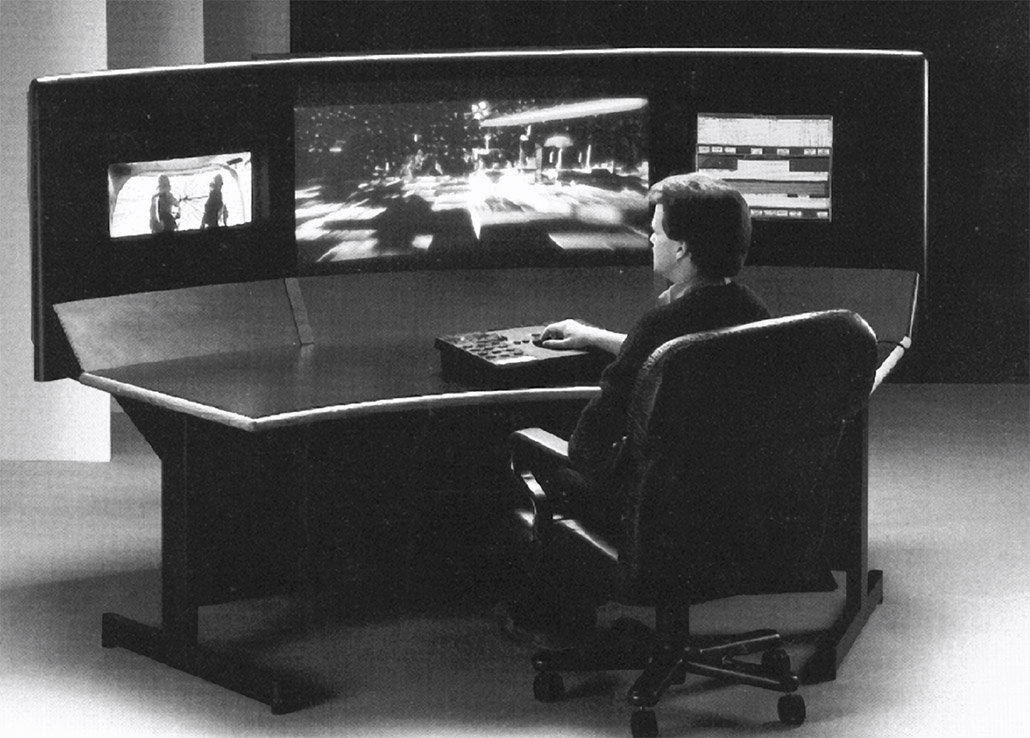

“It was really the EditDroid that was closest to George’s heart,” continues Rubin. “The cold fact of the matter is that whether or not it was a commercial success or failure (just 24 units were manufactured; its principal competitor, the Montage Picture Processor, did only slightly better), by 1984, you can see in that machine an almost perfect simulation of how we work today—in terms of the orientation of the screen, the bit-mapped display with timeline, and the widescreen master display in the middle. It could almost be Final Cut Pro in 2005.”

From the beginning pages of Droidmaker, it is the relationship between Lucas and fellow filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola that drives the story forward. It was Coppola who first foresaw “images and sound and data flowing like hot and cold water” and who, in 1970, said, “I want to use a computer to push a button and instantaneously put together scenes in any combination.” Coppola’s success as a Hollywood anti-hero was a beacon to next generation filmmakers such as Lucas, Walter Murch, ACE and Steven Spielberg.

“George and Francis didn’t work together, they worked in parallel,” explains Rubin. “They had different ideas. George is more visual- and sound-oriented; Francis is more script- and drama-driven. George is more plodding and a builder; Francis is more daring and reckless and a dabbler. They were friends and they swirled around and inspired each other. Francis may have said, ‘We can build this with a computer,’ but George may not have believed it until his computer guys created a motion control camera; then he might say, ‘Hey, computers are pretty cool.’ They both foresaw a time when film would be replaced by a digital, high-resolution alternative that was neither film nor video. They both wanted to revolutionize the industry, but for different reasons.”

Rubin wrote Droidmaker to address a need to tell a story no one else had told before. “The Lucasfilm computer division was at least as influential on modern media as Xerox PARC [Palo Alto Research Center], another technology birthplace,” he says. “It was really starting to irk me that after 20 years, no one was giving the division its due. I wrote it because I was familiar with the story, because I was there and I wanted to tell the story while people were still around and I could still find them.”

Lucasfilm, he says, was remarkably cooperative with the research. “They recognized that I was not only an alumnus of the company, but an educator who had written a lot of books that they liked,” Rubin says. “George appreciated that I was sensitive to the politics of the company. When I first made my pitch and told them I wanted to interview lots of old employees, including George, I felt as if I was arguing a case before the Supreme Court. I desired and asked for their cooperation in order for the book to be both complete and historically relevant. But as much as I wanted their cooperation, I made it clear that for the book to have historical merit, I had to be independent and free from oversight. They agreed. By the same token, because I have no affiliation with Lucasfilm, I don’t expect them to promote the book for me, or to facilitate its launch. That’s the double-edged sword and the price of independence.”

If Droidmaker were a movie, George Lucas’ actual screen time would be severely limited. None-the-less, his imprimatur hangs over everything in the book. In several spots, Lucas is a quiet figure sitting in the back of the room chiming in with a simple, “Sounds good,” as some groundbreaking solution floats across the table. “That’s who George is,” Rubin explains. “He’s got a million projects going all the time and doesn’t give any one thing a lot of time. He just needs to keep all the plates spinning.”

Michael Rubin

And that may explain the enormous importance of the computer division. George Lucas’ financial success made it possible for Lucasfilm to become the first studio to fund pure research for the entertainment industry. If Droidmaker was talking about Xerox or Sun Microsystems, we would not be talking about entertainment research, even if that were the endgame.

“Most technology research doesn’t happen the way it did at Lucasfilm, which was to focus on making tools for himself and for the people who do this work,” he says. “Initially, there was no market analysis, no cost benefit exploration. George stuck a stake in the ground and said, ‘We need to discover what true film resolution is, what that means in terms of geometry, and then we will make the right tool.’ These are problems that could only be solved at a film company.”

George Lucas never wanted to be in the equipment manufacturing business. Had tools like the EditDrioid, SoundDroid and the Pixar graphics computer been available in stores, he would simply have gone out and bought them. “It’s not that Lucas had an urge to invent,” adds Rubin. “But these things didn’t exist, and he had no option but to make them himself.”

Once those products were created, Lucas began selling them off, marking the end of the computer division. Like anything created at Lucasfilm for internal purposes, the commercial possibilities became obvious almost immediately. “Once that happened, you now would have to further develop product for a marketplace that had very different wish lists and needs. It was a different world order and it wasn’t the world George wanted his company to be in.”

“The Lucasfilm computer division was at least as influential on modern media as Xerox PARC [Palo Alto Research Center], another technology birthplace,” – Michael Rubin

For Rubin, all the efforts paid off when Murch won his Oscar for editing The English Patient in 1997. “I thought, ‘How fabulous that the [nonlinear system] Avid had finally become respectable and mainstream enough that a film cut on it could win an Academy Award. That it was Walter Murch who did it on a film that wasn’t one of Francis’ or George’s was even more satisfying,” he enthuses. “George’s stamp on nonlinear editing was the EditDroid, while Francis embraced the Montage, but in the end, it was neither of them who won the race. Walter legitimized the [NLE] Avid in a lot of ways when he won, and it was a wonderful moment; a poignant climax for all the years of hard work and passion.”

Since Droidmaker’s publication, Rubin has been an evangelist for himself, engineering a four-month national book tour that included an emotional stop at Pixar that re-united him with many of the players—Tom Porter, Catmull, Carpenter, Lasseter and others—who signed his copy of the book. The tour will culminate on January 11 with the keynote address at MacWorld in San Francisco and a final stop at the Sundance Film Festival.

Ultimately, Rubin hopes that his respect for all these creators shines through the pages of Droidmaker. “They are the coolest, most passionate people I’ve ever met,” he summarizes. “Even at the time it was all happening, all of us recognized that this was a kind of hallowed place in space and time. Something magical was happening on Kerner Boulevard.