by Debbie Berman

“…and it’s being shot completely in Arabic.”

Say what?

I fervently hoped that the webcam pixelation hid the panic I could feel creeping into my eyes. I took a deep breath and decided not to let minor details such as my complete inability to under- stand the above-mentioned language dull any initial excitement. After all, this was an interview, and the words “Disney” and “shoot- ing in Jordan” had already been thrown out there. I couldn’t ignore the thrill of a potential Middle Eastern adventure.

So I said what any picture editor would say when faced with a challenge that seems ridiculously insurmountable, yet utterly enticing: “Sounds great!”

And then they asked the question: “So how do you plan to do it?”

Apparently, the original editor, whose involvement on the film had fallen through, possessed all sorts of weird, appropriate, special skills — such as speaking Arabic. There was to be an impossibly short post schedule, and the producer needed a perfect answer to dull any initial fears that an English-speaking Jewish South African could edit a film shot entirely in the Arabic language.

“I’ll get back to you,” I assured them.

I started racing through all potential workflows in my head. The most obvious solution would be to simply listen to the takes over and over, and then essentially cut the scenes blind with a translated script as a reference. Another alternative could be to get all the dailies subtitled pre-editing, and start cutting from those sequences. I’d no longer be cutting blindly, but that would be exceptionally time-consuming to set up, and I knew that we would not have the manpower or schedule to enable us to do so.

Even though I knew them to be commonly used, neither of these options felt ideal. I was certain that a more efficient methodology must be possible. As it turns out, desperation is a great motivator for in- novation.

After a substantial amount of pacing, muttering to myself and glaring at my lap- top, the answer finally came to me. I flashed back to a (now astonishingly serendipitous) meeting I had with Robert Bramwell, master of Avid’s ScriptSync, a few weeks earlier. I had been looking over his shoulder at some- thing strange I had not seen on the Avid before.

“What is that?” I queried. “That,” he replied, “is ScriptSync.”

Ah, ScriptSync. I had heard of it before, seen the options in the menu and randomly pushed the shortcut buttons in the Command Palette. I had always wondered how one used it, technically.

In a nutshell, ScriptSync is a Media Composer feature that allows you to import your screenplay into the Avid, and then lets you work with an interactive version of it. Thus, instead of manually wading through the clips in your bin to find specific sections of each take, you can find them instantly by simply clicking on that line in the script, and having it play back that moment in the clip. It can be automated through phonetics, or manually synched. It is especially useful when sitting in editing sessions with all sorts of important people, and allows you to bypass any desperate scroll- ing and searching. Essentially, it turns you into Super Editor.

Then, the master’s life-changing words: “Let me show you how it works.” (Thank you, Robert!)

So there I was, sitting in a dust-filled edit suite in Jordan. Something on the news about possible turmoil feared in the Middle East due to political uprising in Tunisia. But that’s another story. Let’s just say that the night Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak resigned, I think the entire population of Jordan was celebrating in the streets outside the Egyptian Embassy (also known as the building next to our hotel), and that by the time we returned to LA several weeks later, the world had changed.

But back to the dirty edit suite in Jordan. I’d been told that The Hurt Locker had been cut in this exact room and I hoped for some residual brilliance to still be in the air. I was yet to find some- one who already had used ScriptSync as a translation tool, but was certain that it had been — and could be — done.

Initially, I had hoped to fully automate the process as Arabic was listed as a supported ScriptSync language. My plan was to import a version of the screenplay that alternated constantly between Arabic script and its English translation, then automate to the Arabic and cut referencing the English. However, we were having some issues importing the script into the Avid. I posted a question on the Avid User Forum, confident that I would have several excellent technical solutions within the hour. Turns out that not a lot of people on the user forum were trying to use ScriptSync to cut in Arabic.

That’s when Avid principal product designer Michael Phillips (now no longer with the company) saw my poor, neglected posting and contacted me directly, asking for some test files. He was absolutely fantastic and helpful, and said that we couldn’t bring our Arabic into ScriptSync as our script “does not include diacritics — basically, vowels. Diacritics are typically included in children’s books and learning materials in order to make the wording as explicit as possible.” Michael said that our files had pointed to an issue with the Arabic language that was not taken into account with ScriptSync’s particular language pack, but that Avid’s technology provider Nexidia would be providing this for the next update.

I was thrilled by the fantastic customer support we were get- ting through a mere blind posting on the Avid forum. However, it would still be some time until its new phonetic software would be available, and we were going to camera in the morning. It was time for my back-up plan, which I was pretty sure would probably work.

This is where having an amazing assistant editor who speaks the native tongue comes in. I was lucky enough to have a partner in crime with a great story sense who spoke Arabic fluently. Lara Mazzawi saved me by manually synching the spoken Arabic lines in the clips to the English writing on the script. This ultimately ended up being a superior idea to my initial one of having the English translation under the automated synched Arabic writing. The automated synching would have saved some time, but linking the dialogue directly to the English words was a lot cleaner way for me to work.

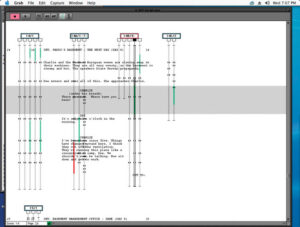

Lara would start off by adjusting the shooting script to any dialogue changes that had happened on set. Then, she’d import that into the Avid and manually sync the English writing on the script to the correlating spoken Arabic in the clip. Circled takes were marked in ScriptSync by coloring them green. Any deviations from the script were marked by red, an indicator for me to check the corresponding red locators on the clip for their individual translations — which often reflected changes in tone, intention or simply humorous improv. I’m a big believer in color-coding as many things as possible, as this provides an instant visual reference. I like to look at an array of colors that immediately tells me details about what I am looking at, both technically and creatively. Besides, it makes my Avid look pretty.

It was magic, almost too easy. I would click on the sentence in the script in English, and it would play back in the clip in Arabic; alternatively, I could listen to the line in Arabic, and backtrack it to the English translation in the script. It was beautiful, wonderful, simple. Sitting with Amin Matalqa, our fabulously talented — and bilingual — director, it was all too easy to play the differing takes in a row should he want to compare performances.

Without it, I can imagine lots of frustrated scrolling back and forth through large clips trying to find the same lines in different takes, looking for words I didn’t understand that were preceded or followed by a bunch of other words I didn’t understand, and that all sounded pretty similar to me in the first place. Using Script- Sync, the comparisons were instantaneous. With a few simple clicks, all the differing takes of an individual line would play one after the other. Referencing the English translation was only a click away.

As the project progressed, I found that while I was initially cutting the sequence, I would remember the English meaning of the words and had no issue with following the dialogue upon playback. However, a few days and many other scenes later, I could only recall the overall intent of the scene, and not the specific sentences anymore.

It was then that I recalled the wise words of editor Gary Roach, who, after cutting in Japanese on Letters from Iwo Jima and in French on Hereafter (and receiving a “you have to help!” e-mail from me), had advised me to “get those subtitles in as soon as possible.” It was fantastic advice. Shortly after returning from the shoot, we did just that. It was kind of a thrill “re-watching” the movie and understanding word for word the significance of the lines, especially as I had initially cut everything out of order several weeks earlier.

I still really treasured my non-subtitle edits; I’d never cut on such pure emotional instinct before. My choices were based on overall intent and tone, as opposed to fully understanding the way that intonation on certain words changed the impact of the performance. I tried to stay true to the intuitive nature of that. Once those subtitles were in, I had to make a conscious effort not to constantly “read” the movie, and would alternate working with the title layer activated to understand the specifics, and with the title layer deactivated to focus on the emotion. It was also important to ensure that the timing of the edits worked with and without reading the subtitles, so that the film could serve both local and international audiences.

I absolutely could not have cut this film in our insanely short time frame without ScriptSync. Not only did it save time, but it eradicated the potential of any traumatic language-barrier breakdowns (both personal and technical). It was a brilliant and wonderful experience.

Also crucial to any technology are the people who enable you to use that technology. Without the support from producer Rachel Gandin and Director Amin Matalqa, the tireless work of my assistant Lara Mazzawi, the generous advice of editing mentors such as Robert Bramwell and Gary Roach, and the technical assistance from Avid and Nexidia, I am pretty sure I would have been staging my own Arabic protest a few days into the shoot.

Editor’s Note: The film edited by the author is The United, Disney’s first feature film in the Arabic language. It involves a legendary Egyptian football coach brought back from retirement to train a team of pan-Arab misfits in Jordan, and is scheduled for release in the first quarter of 2012.