By Peter Tonguette

Forget raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens. Here are some of picture editor Matthew Hannam’s favorite things: Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye,” Michael Mann’s “Thief,” David Cronenberg’s far-out adaptation of “Naked Lunch,” Lawrence Kasdan’s “Body Heat,” the cinema of Chevy Chase, and the film scores of Danny Elfman.

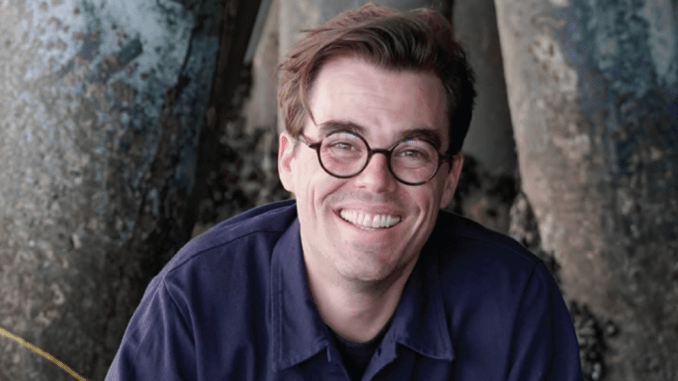

Hannam was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, but as a child of the 1980s, he avidly consumed movies and shows not only made in his own country but those produced in that big popular culture factory across the border: Hollywood. “I’m the cliché: kid watching movies in the basement,” said Hannam, who put his wide and deep appreciation of pop culture to good use in his latest film, Oscar-nominated director Noah Baumbach’s new phantasmagoria of comedy, drama, suspense, and satire, “White Noise.” Hannam recently sat down with CineMontage to talk about the movie — and the many movies that informed its making.

Based on the celebrated 1985 novel by the iconic American author Don DeLillo, the film stars Adam Driver as Jack Gladney, a professor who specializes in an arcane field at a college somewhere in middle America in the 1980s. Jack and his outwardly bubbly (and inwardly troubled) wife Babette (Greta Gerwig) are parents to a drove of children and stepchildren — including, most importantly, Babette’s daughter from a previous marriage, Denise (Raffey Cassidy) — who flit about their cramped suburban house and haunt the aisles of the nearby A&P supermarket.

‘We wanted a warm family story.’

Over the course of the film, which Netflix released in theaters on Nov. 25 and which became available on the streaming service on Dec. 30, the Gladney family contends with several crises, including Babette’s addiction to a strange drug, Dylar, and the emergence of a toxic cloud following a train crash. If both incidents compel Jack to ponder his own mortality, the world of the film — full of the movies, fashions, and merchandise of the 1980s — serves to distract him. In a way, that’s the point.

“It’s like as long as you are in the shopping center, you’re going to be safe because everyone else is there doing the same thing,” Hannam said. “But the second you put your neck out and do something on your own, you could die. I think that’s a really salient concept.”

That all may sound heavy, but in truth, “White Noise” is bright, bold, and fun. Anchored by Driver and Gerwig’s appealingly cockeyed performances, the film at least in part embraces the consumerism it parodies. “There is the satirical, weird spirit of celebrating commerce as well as being firmly anti-commerce,” Hannam said. “We didn’t want to be a negative downer of a ‘White Noise.’ We wanted it to be a warm family story.”

‘The second you put your neck out, you could die.’

With his encyclopedic grasp of high and low 1980s pop culture, Hannam, who had not previously collaborated with Baumbach, was an inspired choice to edit “White Noise.” “I met Noah and we hit it off,” Hannam said. “I said, ‘I was born to make this movie: I love the ’80s, I love assertive American literature from this period.’ We talked a lot about books and writers.” And, for his part, Baumbach recognized a kindred spirit in Hannam. “I like to involve the editor from the early drafts of the script onward so our process started quite early, and I’m in the editing room every day, so we had to really get along,” Baumbach said in a statement to CineMontage. “Matt has a great sense of rhythm and storytelling, as well as knowing good places to eat and shop for clothes. It was a very happy collaboration.”

For Baumbach, whose earlier films include “The Squid and the Whale” (2005), “Frances Ha” (2012), and “Marriage Story” (2019), “White Noise” was by far his biggest and most ambitious picture, and Hannam was brought in on the ground floor. “I was in Cleveland for about five months, and a month of that was prep time,” Hannam said about the film, which was photographed in locations throughout northeast Ohio. “We went on location scouts, and I would work on little cuts of things and cutting storyboards. We had a storyboard artist, who’s a good friend of mine, who came on.”

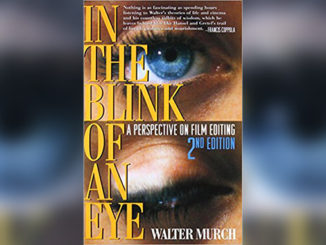

Throughout, Hannam immersed himself in the movies of the period — at one point, the editor sent Baumbach a bunch of scenes from Mann’s “Thief” for no particular reason other than he felt it related in some way to what they were working on — as well as the inimitable authorial voice of DeLillo, of whom he was already an admirer. “I always had a copy of the book around, and then, during the editing, I actually just listened to a lot of DeLillo [on audiobooks] on my walk to and from work,” Hannam said. “I really loved ‘Mao II.’ That was one that I listened to. It was interesting, because there’s a certain rhythm to his dialogue and an illustrative quality to the writing that I thought might be inspiring.”

Before Baumbach became involved in the project, “White Noise” had been bandied about as a possible film for years. Perhaps it even had the reputation of being unfilmable, but Hannam rejects that notion. He feels that Baumbach took a dense, sprawling novel and found what he calls its narrative engine: Babette’s addiction to Dylar, and Jack’s attempts to uncover her abuse of the drug. “One of the parts of the movie Noah and I talked about the most was [Jack’s] relationship with Denise, and the sort of Nancy Drew subplot of her trying to find the Dylar,” Hannam said. “That was something that was really one of the inventions that Noah had that made the movie really tick as a movie. . . . That was always the engine of the edit.”

That didn’t mean that there weren’t challenges to making DeLillo’s work play as cinema. The author’s dialogue is arch, stilted, and very self-conscious, and so are the lines in Baumbach’s adaptation. For Hannam, it’s a matter of being confident in the sound of DeLillo’s language. “It starts with a writer who’s got the guts to put it down and not shy away from it when the actors show up, and about casting actors that have the ability, the chops to do it,” Hannam said. “Adam and Greta were able to do that stuff.” But then it’s up to the editor to trust the material, he said. “Just stick to it and not cut it up too much,” Hannam said. “You have to really let it be what it is and preserve the musicality of it.”

Yet “White Noise” isn’t a film in which a great author’s dialogue is treated preciously. Instead, Baumbach and Hannam created chaotic, cacophonous scenes in which characters chatter. In an early scene in the kitchen, parents and offspring gab at each other relentlessly. “We talked a lot about ’80s Altman,” Hannam said, referring to the great filmmaker’s penchant for overlapping dialogue. “We wanted it to feel like you were dropped into a family that didn’t really care about the movie…. They are a family, and the reality of a family is that there’s no setup.”

The kitchen scene features Jack navigating two sides of the room, each engaged in their own overlapping conversations. “We moved the camera in a way that would energetically link side to side, and we had it covered in different sizes,” Hannam said. “All of the shots hinged into other setups. The camera would depart one character and stick on another so the person could pass through that conversation, land in a new conversation, and pass back through.”

Hannam describes “White Noise” as consisting of “layers” — of image, sound, music, even TV commercials heard in the background. “We scored the movie with commercials and TV shows,” Hannam said. “All the commercials were done practically on-set. I would cut TV content, and we had it cued up for every scene. We always had an idea of the media content of the scene.” Also essential to the production was the music of composer Danny Elfman. “Scoring with Danny and using Danny’s music is different than anyone else because it’s got a buoyancy to it that lives in a cinema landscape,” Hannam said. “He’s just an absolute original.”

One of the film’s most memorable scenes intercuts competing presentations by Jack and his colleague Murray (Don Cheadle) — with Jack discussing his academic specialty, Hitler; and Murray talking about the focus of his research, Elvis Presley — with the collision between a train and a truck that results in the toxic cloud that eventually sends Jack, Babette, and their kids to pack up the car and get out of town. “In the editing room, we called it the dueling lectures,” Hannam said. “The movie we looked at a lot for that sequence was [Steven Spielberg’s] ‘Duel.’”

When it came time to shoot the classroom portion of the sequence, however, the company only had two days to work. “I was sitting on the set with Noah, next to the monitor, and we’re looking at our storyboards, and it was like: We’re just shooting this the best we can,” Hannam said. “There is no way that we can stop these actors and these performances and be like: ‘OK, can you swing your arm because it’s going to match a train that we’re going to shoot in two months?’” Consequently, the train collision was designed around the footage that was captured in the classroom. “It was just about finding footage that matched well,” Hannam said.

Although Baumbach and Hannam made use of storyboards — a first for both men — the editor adopted a far looser approach during post-production. As he has on a number of recent films, Hannam dispensed with the usual routine of preparing an assembly from which he then works with the director. “Which frees me up to just cut scenes and say, ‘Hey, this could be cool to do next,’ or, ‘I think we could use this shot,’” he said, adding, “Noah is a very open and collaborative guy, but he also knows exactly what he wants to do.” Scenes would be cut and recut until Baumbach and Hannam were satisfied, and then they would go to work on another scene, usually those surrounding the cut scene. “You just move inch by inch through the movie until you get to the end [and] it took us a long time to get to a [full] cut,” Hannam said. “We would show half of the movie to a few people and talk about that, and then rework that.” Lots of things were tried, but the movie’s soul stayed the same.

Hannam describes the role of the editor as that of a harmonizer of sorts. “My job as an editor is to bring together the elements that let the film present itself with all pistons firing,” he said. Few recent American movies have as many pistons firing as “White Noise” — making it the perfect assignment for the kid from Winnipeg who watched so many movies and so much TV.

“That’s why I loved making this movie so much,” Hannam said. “Noah is older than I am, but in a way we met each other on a lot of levels — musically and literature-wise and cinema-wise.”