by Edward Landler

Kurt Vonnegut dedicated his 1976 novel Slapstick “to the memory of Arthur Stanley Jefferson and Norvell Hardy” — better known as Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. In the novel’s prologue, the author explains, “I have called it Slapstick because it is grotesque, situational poetry, like the slapstick film comedies, especially those of Laurel and Hardy… There was often the situational poetry of marriage, which was something else again. It was yet another test — with comical possibilities…”

Those possibilities of that “something else again” were most richly played out in the best of Laurel and Hardy’s feature-length films, Sons of the Desert, released on December 29, 1933. This was their fourth feature, but the first that fully integrated their routines and gags from scene to scene into a story built around their characters’ personal lives instead of playing off typical movie genres. And by coincidence, one day shy of Sons’ 85th anniversary, the new British-made feature Stan & Ollie opens on US screens, starring Steve Coogan and John C. Reilly, respectively, portraying the real-life team in 1953.

In Sons of the Desert, however, the Laurel and Hardy characters are loyal members of Oasis 13 of the fraternal organization that gives the film its title. Reworking a premise from their 1928 two-reel silent We Faw Down, they pretend they are going to Honolulu for Hardy’s health to keep their wives from knowing they are really going to the Sons’ Chicago convention.

With the benefits of extended length, sound and a “solemn pledge” to their lodge, the childlike comics direct our laughter at the consequences of their subterfuge and poke jabs at commonly held attitudes about being men and being married. Audiences of the time responded by making Sons one of the top-10-grossing movies of 1934 (according to both Film Daily and the Motion Picture Herald). The laughter has continued: In 2012, the comedy was added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry, joining their previously selected short films Big Business (1929) and The Music Box (1932).

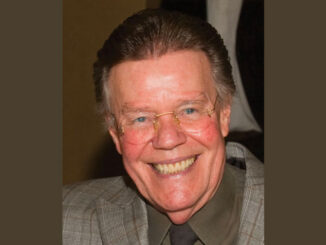

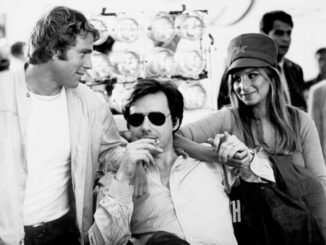

MGM/Photofest

The English Laurel and the US-born Hardy arrived separately in Los Angeles in 1917. By 1925, they were both on the Hal Roach Studios payroll — Hardy as an actor and Laurel as an actor, writer and director. In 1927, they appeared together in no less than 10 two-reelers, but as unrelated characters, not as a team.

It soon became apparent to producer Roach and others at the studio that the physical contrast between the tall, stout Hardy and the short, thin Laurel was inherently funny. At the end of 1927, they starred together in their first official Laurel and Hardy two-reel comedy, Putting Pants on Philip. Their popularity was infectious, and the now-iconic duo immediately became an established team making silent two-reelers.

Laurel never received credit as writer or director on any of their movies, and only two of the pair’s later features were credited as Stan Laurel Productions. Nevertheless, there was never any doubt at the studio that it was Laurel who guided the writers, directors, actors and crew, while Hardy spent much of his time between shoots playing golf.

“Stan was Laurel and Hardy,” declared Roy Seawright in Randy Skretvedt’s 1986 book Laurel and Hardy: The Magic Behind the Movies. The chief of optical effects for Roach Studios from 1927 to 1940, Seawright recalled, “I loved Babe [Hardy], but Stan was a writer, a director, a cutter — he did everything. I don’t care what the credits say; Stan was the power behind their whole enterprise.”

During the 14 years that the duo worked as a team with Roach, 20 different directors were credited on the roughly 75 shorts and features they made. Viewing their movies to pick out varying directorial approaches or flourishes only confirms Seawright’s statement that one major creative figure was in control of all aspects of production, starting with the script itself.

In a 1959 interview with Boyd Verb in Films in Review, Laurel explained, “We did have a script, but it didn’t consist of the routines and gags. It outlined the basic story idea and was just a plan for us to follow. Oh, a few gags were mentioned here and there in the script, but they were always worked out on the set.”

Laurel insisted on shooting the scripts in sequence to allow for improvisations that could affect later scenes. “We shot our comedies right from beginning to end,” he maintained in the interview. “The only place I could do it was at Roach’s. Anywhere else, they wouldn’t go for that. And many times, not shooting in sequence just ruined the picture, or the prospects for the picture.” Shooting this way also helped them develop the deliberate comic pacing that emphasized the pair’s emotional and mental processes on screen.

This style easily adapted to sound and, in 1931, Roach scheduled them to make one feature for every six two-reelers they turned out. Though their first three features did well at the box office, Laurel was not happy with them. Then, early in July 1933, the studio hired actor/playwright Frank Craven to write a story treatment for the team from an idea entitled Fraternally Yours.

Over the following two months, while Laurel and Hardy were shooting two shorts back-to-back, Craven’s treatment expanded into a script with help from writer Byron Morgan on continuity. At the end of August, William A. Seiter was signed to direct. An accomplished Hollywood stalwart with almost 150 directing credits stretching from 1915 to 1960 and encompassing shorts, features and television of all genres, Seiter made only this one film (eventually renamed Sons of the Desert) with his close friend Laurel.

According to Bert Jordan, “officially named the Laurel and Hardy film editor,” Stan Laurel had the right of final cut and supervised the editing of each sequence of all the pictures on which he worked.

Seiter and Laurel, with Roach company regulars joining in for brainstorming, worked on the script through September, but the director felt they had no clear ideas for staging the convention scenes. Fortunately, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks held its national convention in Santa Monica that month and the director and his stars were able to observe it for themselves.

On September 28, the script was considered sufficiently complete for shooting to begin October 2. Comedienne Patsy Kelly was originally cast as Laurel’s wife, but she had been loaned out to MGM for Going Hollywood (1933). When that picture went over schedule, the part of Laurel’s wife was given to Dorothy Christy, who joined the cast four days after Sons started filming. Hardy’s wife was played by Mae Busch, who appeared in 12 Laurel and Hardy pictures over seven years, four times as Mrs. Hardy.

True to form, shooting began with the first scene: The local meeting of the Sons of the Desert, filmed on location at the Hollywood American Legion Post with 20 legionnaires among the 60 extras playing the Sons. Director of photography Kenneth Peach, ASC, played with dramatic lighting on the face of the Grand Exalted Ruler but, like all of the team’s cinematographers, was required to keep the lighting as flat as possible on the faces of the two stars.

MGM/Photofest

Also true to form, whole routines appear in the movie that were not in the final script, now in the Production Code Administration records in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library. In the script, the lodge members stand up throughout the opening scene, but are seated in chairs in the film so that Laurel and Hardy’s late entrance can properly disrupt them.

Soon afterwards, Laurel waits in next-door neighbor Hardy’s house for his own wife to get home. During filming, Laurel was inspired to devise the torturous process of eating an apple from a bowl of wax fruit. The surreal image of Laurel’s wife entering with a rifle and a brace of dead ducks was also invented on set; in the script, she was just returning from target practice.

The final sequence of the movie was shot as scripted; with the husbands coming home to learn their supposed cruise back from Hawaii was caught up in a hurricane, they hide from their wives in the attic, then on the roof. Although those sequences were originally filmed in daylight, it was decided to reshoot most of them at night in a simulated downpour, enhancing the gags considerably.

Two big gag scenes written for the convention were not filmed at all. Instead, Roach comedian Charley Chase’s performance as an obnoxious Texas lodge member, wielding an actual two-ply slapstick, was allowed to drive the comedy at a swifter pace. But the first convention scene — the Sons of the Desert parading in the streets, also seen later in a newsreel in the film — had to be shot out of continuity at the end of the shoot.

MGM/Photofest

Before production, on one of his trips to the Elks convention, director Seiter had taken a small film crew to shoot the Elks on parade in the Santa Monica streets. He and Laurel planned to use these long shots as masters and cut in closer views of the Sons in the parade to be shot on the Roach lot’s city street set. Returning to the lot, though, they realized Roach’s city street did not look contemporary enough to cut together with the Santa Monica footage.

Roach decided to modernize and expand his set at a cost of $25,000. Postponing the parade shoot, he had four crews work around the clock to complete 500 feet of new facades in time to avoid extending the production schedule. When they finally filmed on the lot, over 500 extras (including the drill team of the American Legion’s Glendale post) marched on the new set — a studio record for the number of extras used on any film at one time.

By the time production wrapped on October 23, editor Bert Jordan had already started cutting. In 1939, he would go on to edit Lewis Milestone’s adaptation of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, produced for Roach. But early in his career, in 1932, Jordan “was officially named the Laurel and Hardy film editor,” as he told movie historian Skretvedt in 1980.

According to the editor, Laurel had the right of final cut and supervised the editing of each sequence of all the pictures on which he worked. “I used to be on the set as much as I could,” he attested to Skretvedt. “After I put together my version, the director and Stan would look at it, and they had the privilege of making changes… Mr. Roach would sometimes…suggest some changes — but if Stan didn’t agree with them, they weren’t changed.”

When the movie was released, critic Andre Sennwald of The New York Times noted the difference between Sons and Laurel and Hardy’s earlier features. He wrote that it “has achieved feature length without the benefit of the usual distressing formulae [sic] of padding and stretching. It is funny all the way through.”

The popularity of this unique pair of comedians and this film endures to this day in the real-world Sons of the Desert, a fraternal organization devoted to their memory and their films. Founded by the duo’s biographer John McCabe in New York City in 1964, the organization boasts more than 100 “tents” active worldwide today.

And for all who laugh with them, Laurel and Hardy’s endearing innocence and sustained lack of insight resonate deeply in our everyday human existence. It is surely no accident that the team’s mutual dependence and cluelessness is reflected in the bowler-wearing Vladimir and Estragon of Samuel Beckett’s 1952 tragi-comedy in two acts, Waiting for Godot.

Given the world’s present predicament, let us at least find a modicum of wisdom in simple-minded Laurel’s last line to Hardy in Sons of the Desert: “Honesty is the best politics.”