by Michael Knue, ACE

Ghosts. I guess we’re never very far from them. You can’t really see them, but they’re always there. They’re quiet. Every now and then, one pops up, moves the furniture and leaves. You turn around to see the drapes swish and your life has changed. What was that!?

“What’s the deal with your credits?” the producer asked me. “Half of them have the word ‘death’ in the title and the rest are about ghosts!” Well, maybe not half. I admit I’ve cut a few more genre movies than most editors, but it never was my intention. They just kind of…appeared, you know? Like out of nowhere.

I’m fairly comfortable with ghosts and apparitions. Always have been. In my mother’s Catholic household, it was assumed that saints and other deceased holies could pop out of the woodwork at any time to say hi and ask for a rosary. Whenever Saturday Night at the Movies telecast Song of Bernadette, it was treated as a Holy Day. After my grandmother died, my grandfather came to live with us. He’d have nightly chats with grandma before he went to bed.

Dad fixed TV sets in his basement workshop in those days. So my evenings were spent with him, watching a fluttering RCA set on its side while he made adjustments from the back. That’s pretty much how I viewed television in the 1950s: Ghostly images that rolled across a sideways TV screen. That, too, was my first exposure to Topper, the TV series with Leo G. Carroll (1953-1955). It wasn’t until years later, with the arrival of VHS, that I watched the original 1937 film, Topper, starring Roland Young as Cosmo Topper, Cary Grant as George Kerby and Constance Bennett as Marion Kerby.

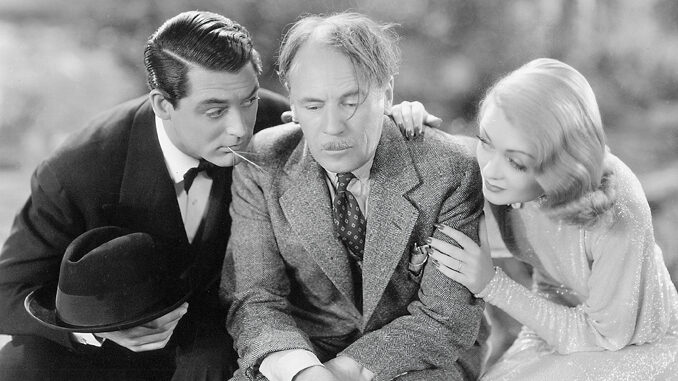

Cosmo Topper is the staid president of a New York bank. His life is regular and unchanging, managed by his priggish wife, Clara (the wonderful Billie Burke). “Beef on Tuesdays, boiled vegetables on Thursdays.” The thorn in Topper’s side is George Kerby, a very wealthy but charmingly irresponsible partier and his equally charming and irresponsible wife, Marion. George is on the bank’s board of directors and loves to taunt Topper about his conservative life. Marion, however, has a different effect on Topper. Like the perfume in her handkerchief, she infects Cosmo with her liberal ways. “Toppie, why don’t you stop being a mummy for a minute and come to life?”

On the Kerbys’ return from the board meeting, George drives recklessly, losing control and crashing. The two climb out of the wreck — and their own bodies — and realize that they are dead. When the heavenly hosts don’t come to get them, they figure they need to do a good deed to earn a place in heaven. That good deed, they resolve, is to save Topper from his mundane life.

Topper is upset over the Kerbys’ sudden departure, assessing his own life and his relationship with his wife. When the Kerbys show up as ghosts, Topper is at first befuddled, but soon becomes a reluctant accomplice to their spooky capers.

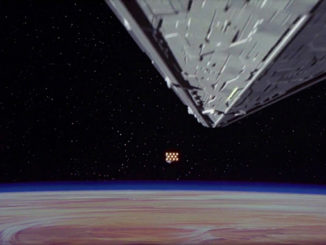

The fun comes from the Kerbys’ ability to appear and disappear. Topper can’t walk through the crowded bank without an invisible Marion tossing up deposit slips behind him. There is a lot of simple animation and mechanical gags, like the car that seems to drive itself or change its own tire. The flying dog is the best! Split screens and jump cuts let the Kerbys “slip” out of frame — editing tricks I’ve used on Ghost Whisperer that haven’t changed in 75 years.

This was the source of the TV series’ humor, too. But the original film is less about the antics of the ghosts and more about the changes in Topper; it could’ve been called “Topper Goes Wild.” The Kerbys may be the source of the jokes, but it’s Topper’s re- evaluation of his life that compels the action. “I won’t go back to that silly old routine; up at eight, bed at 11, lamb on Sundays. I won’t do it!” Topper complains.

I’ve come to really love these films from the 1930s. The essence is in the writing and the performances, not the filmmaking. Topper is like a filmed stage play. Most of the scenes are simply shot in a room set inside a proscenium. Often there is no cutting at all, especially in the scenes between George and Marion. The dialogue is smart, fast and witty. And the performances are impeccable. There’s even a wisecracking butler. In the end, the Kerbys ascend and Topper goes back to his life. But all is not the same.

He’s changed. His wife has changed. The Kerbys’ ghostly presence has been felt.

Leo G. Carroll is talking to no one as his wife walks into the room. “The picture’s rolling, Dad,” I say. “And fading in and out.” Dad, fiddling with the TV, says, “Hmmpf! Ghosts!”